Robbins Cahill

The couple were young and poor, but they had a 1940 Ford and enough soldier’s pay for a honeymoon in Nevada — until they took a stretch-and-soda break at a roadside joint. They paid a silver dime each to tour its “zoo” consisting of a caged coyote, a badger and a few other bedraggled varmints. And deep in the maze of scrap lumber walls, they encountered a tasteful display of beautiful Navajo blankets.

“Well, these blankets are just for the local Indians,” explained the tour guide. “They like blankets and they like to gamble. … But they won’t play the white man’s game. … They want to play a game that they have very little chance of losing.”

Very shortly the couple was playing an “Indian” game with nine dice. The tour guide had metamorphosed into a croupier who totaled dice faster than an adding machine, and swept them up before players could check his addition. On every cast he announced a “standoff” number which neither won nor lost, but required the honeymooners to double their bets in order to continue playing. Of course, the couple soon ran out of money, were unable to make a compulsory raise and forfeited all they had previously bet.

Robbins Cahill tore his hair every time he heard the story. He was charged with regulating gaming in Nevada, and in the 1940s, “zoo joints” were a time bomb waiting to blow Nevada’s reputation sky-high. They chose victims carefully — people unlikely to complain. Sometimes, the operators followed departing pigeons to the nearest town, and if they parked anywhere near a police station, the zoo joint’s operator would suggest to them that it would be healthier to keep driving.

When Cahill finally found a couple who wouldn’t be intimidated, he guarded them round the clock, even though gaming authorities didn’t yet have police powers. Working in shifts, Cahill and a buddy stood vigil all night in the hallway outside the couple’s hotel room. They accompanied the man to a barber shop and the woman to a beauty shop, and finally to the door of a grand jury hearing room in Elko. Then Cahill and his friend threw hunting rifles into their car and guarded the couple’s backs as far as the state line. When an indictment finally materialized, the con game and its operator simply disappeared.

Today, Nevada has a gaming control system said to be the most effective of any jurisdiction with legal gambling. Much of the credit for inventing that system goes to Robbins Cahill, and he started by enforcing two elementary rules: You had to have a license, and you had to run a square game.

Cahill was born in Ogden, Utah, in 1905. He spent his childhood in the Nevada railroad town of Sparks, where his father was stationed as a conductor and his mother ran a rooming house for railroad men. Cahill attended the University of Nevada in Reno, where he was a popular fraternity man, he confessed in his old age, largely because of his friendships with Sparks bootleggers.

Cahill was doing well in the corporate world until the Depression blew it apart. He drifted back to Sparks and a job as a grease monkey. “It was not easy to go back to your hometown as a college graduate … to work in a job that I could’ve worked at when I left the eighth grade,” he said in an oral history recorded by the University of Nevada, Reno, in the 1970s. He saved enough money to open his own garage on a shoestring.

Sparks was a small town that enrolled all the willing, and some who weren’t, for public service. Cahill was drawn into politics as a member of the School Board. He was elected to the Legislature and happened to chair the Ways and Means Committee. In the late ’30s the state was very solvent, reduced the tax rate, and began to brag about it. A sign on the state line announced “Nevada, One Sound State, Cyclone Cellar of the Tax Oppressed, No Sales Tax, No Income Tax, No Inheritance Tax.”

Cahill took a job in the state controller’s office and discovered the state’s lax and patched-together insurance laws permitted promoters to sell insurance policies backed by no assets. He got the code rewritten into a consistent whole.

In 1945 Cahill was appointed secretary to the Nevada Tax Commission, which administered gaming licenses because gaming was seen primarily as a source of license fees. Commissioners were part-timers who met only once in a while, so Cahill did much of their official work.

He had the bad timing to come aboard just as Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel became prominent in Southern Nevada, and Siegel was one of the people who didn’t pay his gaming tax. Cahill sent an employee, Dewey Ebert, to collect the overdue $5,000. Ebert called Cahill from Siegel’s office at the Flamingo, saying Siegel refused to pay. Finally Siegel himself picked up the phone.

“What’ll you do if I don’t pay?” asked Siegel.

“Well, we’ll revoke your license immediately,” said Cahill.

“You wouldn’t dare do it,” said Siegel.

And Cahill responded, “Well, maybe you better try us.”

Siegel still refused to turn over a check, but agreed to write it, and mail it while Ebert watched. When Cahill hung up, his secretary congratulated him for bravery toward a killer.

“Who’s afraid of Bugsy Siegel over the telephone 500 miles away?” Cahill thought. Then he remembered that Ebert had been face to face with a killer who was not called Bugsy for being even-tempered. But Ebert was a brave ex-policeman, and a good bluffer, too.

Bluffing was all he and Cahill were doing, Cahill recalled in an interview with the Review-Journal in 1990. In those days, the Tax Commission didn’t yet have the authority to revoke a license.

In fact, said Cahill in his oral history, it was Siegel’s murder in 1947 that nudged control of gambling out of county hands, where it had resided since legalization in 1931. Las Vegans no longer winked at Siegel’s reputation as a member of Murder Inc. His slaying put the town into an uproar, and P.O. Silvagni, operator of downtown’s Apache Hotel, spoke the fears of all: “Blood is gonna run into the streets!” Suddenly, boosters did care who brought money and where they got it. Because many counties didn’t have the resources to do background checks, they wanted the state to handle it.

Later that year Cahill got an opinion from Attorney General Alan Bible saying the commission had implied authority to investigate backgrounds and deny a license to unsuitable individuals, and in 1949 the Legislature spelled it out in statutes. It also permitted the commission to require fingerprinting of gaming employees, which drove many an outlaw from the trade and reduced the probability of cheating.

One of the bigger challenges to the state’s licensing authority was the Thunderbird incident, precipitated by a Byzantine sting in which an undercover agent, posing as a criminal seeking to bribe his way into a liquor license for a move into Las Vegas, recorded compromising conversations with public officials.

One of the tapes implied crime lord Meyer Lansky held a hidden interest in the Thunderbird. Cahill’s own follow-up investigation showed a loan from Meyer’s brother, Jake, through an intermediary, to Thunderbird licensee Marion Hicks. In 1955, the Tax Commission moved to revoke the gaming licenses of Hicks and his partner, Lt. Gov. Cliff Jones. “We didn’t have to prove that it was Meyer Lansky’s money,” pointed out Cahill in a 1987 interview with the Review-Journal. A hidden interest was prohibited no matter who held it.

Both sides eventually won in a sense, said Cahill. Courts confirmed the state had authority over the issue. They also ruled a loan did not constitute a hidden interest, so Jones and Hicks got to keep their licenses, although they soon sold the Thunderbird. Hicks died not long after, but Jones went on to hold interests in casinos throughout the world.

Even though Cahill fought to keep the Lanskys out of Nevada, he was criticized all his life for issuing licenses to gamblers with alleged connections to criminal organizations. Much of the controversy centered on Morris “Moe” Dalitz, the most prominent member of the group that took control of the Desert Inn from its financially strapped founder, Wilbur Clark.

Yet Dalitz also was the example Cahill chose to defend his practice. Everywhere his personnel went, in investigating Dalitz’ background, they were told that Dalitz had been involved in selling bootleg whiskey and smuggling it from Canada. But they also were told, “They run a good tight business, they run an ethical business. Yes, maybe they have to pay off people to keep an illegal operation.”

Cahill recalled, “When we brought the point of question, were they Mafia people, were they hoodlums, we were told no. These people are seen in their clubs … they tolerate them. But no, they weren’t Mafia. … They don’t operate in this manner.”

Time proved him right, Cahill claimed. The Desert Inn became one of the more stable and most reputable Las Vegas casinos.

Cahill said often people who had gained gambling experience in illegal operations were the best casino operators. In fact, he believed the casino failures of the ’50s and ’60s were brought on by ventures of “the butcher, the baker, and the candlestick maker” into a business they didn’t understand.

And that’s why he preferred operators who had run a joint before, albeit an illegal one. However, he tried to avoid licensing any more of the Siegel type who practiced murder and extortion.

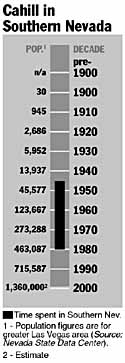

In 1959, at the urging of Gov. Grant Sawyer, the Legislature split the gaming regulatory apparatus away from the Nevada Tax Commission and created the Nevada Gaming Commission. Cahill thought the changes were in order, but chose to remain with the Tax Commission. After four more years he left state government to become Clark County manager.

Harley E. Harmon, who also served on the County Commission in those days, said Cahill professionalized county adminis- tration. “He was probably the most informed man in the state,” said Harmon. “He could give you an answer right now.”

Cahill returned to the gaming business as executive director of the Nevada Resort Association, which represented major resorts in lobbying and labor negotiations, then served three years as executive director of the Gaming Association of Northern Nevada, retiring in 1980.

Cahill was married twice. Elsie Compston Cahill died about 1956 after separating from Cahill; he married Margaret Moffatt Newton, a longtime Las Vegan, in 1957. Margaret died in 1998. They had two sons; Robert Cahill became a teacher in Reno and William Newton a landscape architect in San Francisco.

Robert remembered that his father was easy to get along with, but was so wrapped up in work that he didn’t get to spend as much time with family as everyone would have liked. “He was like most men who had influential positions at the time.”

But in retirement, he made time. In 1994 when Margaret fell ill and had to be moved to an assisted living facility, Cahill refused to be separated from her, and moved there with her. Thought to be in good health for a man of 89, he fell ill that December, and died in a few days.

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full