Ralph Denton

If you have never heard Nevada called “The Mississippi of the West,” it is in large part because of people like Ralph Denton. They fought racism at a time when it was totally acceptable and helped elect reform governor Grant Sawyer, who bashed Jim Crow in the beak.

Denton is a lawyer, a liberal, and a politician — the latter, sporadically. He also is an activist, whether as an attorney, political operative or office holder. To understand the man, one must examine his roots.

“Ralph grew up in a small Nevada town where politics was an art, science and a game, and from a household where politics and ideology came together,” says Michael Green, a professor of history at the Community College of Southern Nevada, who is currently working on an oral history of Denton’s career.

That small town was Caliente, where Ralph Lloyd Denton was born Sept. 8, 1925, the youngest of four children of Floyd and Hazel Denton.

Floyd Denton was undersheriff of Lincoln County, and Hazel, after 35 years as a teacher and school board member, was elected to the Legislature in 1953 and 1955. She supported fellow legislator George Rudiak in his failed effort to pass a state civil rights act. Tolerance was taught in the Denton household.

As a boy, Denton shined shoes at the barber shop in Caliente. “The lawyers and judges used to come up from Las Vegas about once a month,” says Denton. “And they were dressed in fine suits and everybody I knew was dressed in bib overalls or Levis. And it struck me that being a lawyer was a hell of a lot better than shining shoes.”

In the 1930s, with Floyd out of work, the family took in boarders. One day, Bill Roberson, a U.S. Soil and Conservation Service engineer, came to the door and asked if he could take his meals at Hazel Denton’s table. He arrived that evening for dinner and, when he left, a couple of boarders took Hazel Denton aside.

“They told her they didn’t want to have dinner with a nigger,” says Denton. Hazel replied that she thought Mr. Roberson seemed like a nice man, and she had no intention of turning him away. The bigoted boarders grumbled, but didn’t move out.

Roberson became a family friend. In later years, Roberson was Denton’s guest at his home on Oakey Boulevard and took Denton’s children, Mark and Sally, to the nearby White Cross Drug Store for ice cream.

When they returned, Mark seemed puzzled, and asked, “Why couldn’t Uncle Bill have ice cream with us?” The lunch counter had refused service to Roberson. He stood on the sidewalk eating an ice cream cone while the kids sat inside.

Denton attended the University of Utah before enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1943. He earned a second lieutenant’s commission in the field artillery, but saw no combat.

“I used to feel very guilty about that,” he says. “Now, I just feel lucky.”

Denton first met Grant Sawyer in the winter of 1946-47. Both were among the 50 or so “McCarran Boys,” attending law school on patronage jobs provided by powerful U.S. Sen. Patrick McCarran.

“We were all veterans, we were all older than the average college student and we all had developed a healthy respect and regard for strong drink,” laughs Denton.

Denton graduated from law school in 1951. Driving back to Reno, he stopped overnight in Elko, where Sawyer had been elected district attorney.

“We made a few sacrifices on the altar of friendship, and laughed and joked and had a good time, at which time he offered me the job of deputy district attorney if I passed the bar,” says Denton. Denton served from 1951 to 1953.

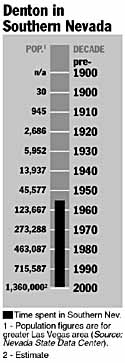

Denton moved to Las Vegas in 1955 and started a private practice.

In 1958, Sawyer decided to run for governor, and Denton, whom Sawyer called “my closest friend,” became his campaign chairman.

“Ralph Denton was willing to stick his neck out and try to organize our campaign in the south,” Sawyer later recalled. “Ralph and I had both been quite active in the party, and were always in the same conspiracies when it came to Democratic conventions. He was liberal and he was gutsy, and we were pretty much soul mates on political issues.”

In the 1958 Democratic primary, Sawyer beat Attorney General Harvey Dickerson and George Franklin, taking about one-third of the Clark County Democratic vote.

“And all of a sudden all these so-called big shots are beating down the door,” Denton laughs. Sawyer headquarters on Fourth Street was visited by some of the state’s most prominent Democrats — including “The Big Juice” himself, former Lt. Gov. Clifford Jones.

Now in the mainstream, and with a good following in the northern counties, Sawyer beat popular incumbent Charles Russell by more than 16,000 votes.

“We didn’t have a federal civil rights act when Grant became governor,” says Denton. “So everything for civil rights was a struggle.” While Sawyer tried to coax state civil rights laws from the Legislature, Denton tried to coax decisions out of judges and juries. He also raised eyebrows when he hired the town’s first black legal secretary, Micki McMillan.

“We did ACLU cases,” says Denton. “In those days, to say anything good about the ACLU was to brand you as a communist. So there were two or three lawyers here, George Rudiak, Dean Breeze and I, who would handle ACLU cases, but we didn’t want anybody to know they were ACLU cases.”

But one of his most significant civil rights cases was home-grown.

“I take some pride in the fact that I represented a black guy in what I think was the first suit against a police department for police brutality.”

The man was skycap Cliff Burns. The time was the early 1960s. He was married with kids, but liked to occasionally acquire a bottle and a bimbo. On one occasion, Burns was driving a sporting lady home when a quarrel erupted. He kicked her out of the car and went home.

The next day the North Las Vegas police knocked on Burns’ door. The woman had accused him of stealing her purse. The cops marched him out to his car and, sure enough, there it was, on the seat.

“Cliff’s madder than hell, of course,” Denton recalls, “and he shoots his mouth off. And they work him over pretty good; they beat the hell out of him. He winds up in the hospital as a result of these beatings, and he’s blind in one of his eyes.”

Medical reports showed the blindness resulted from trauma, and Denton filed suit, asking for $300,000, confident of victory. But the defense did some deep research on Burns.

“They checked his drivers’ license records wherever he’d been, and lo and behold, when he’d got his drivers license 20 years before, he was blind in that left eye.”

Burns had not shared this fact with Denton, who then had to make his closing argument to the jury.

“I guess I asked for too much money in this case,” Denton told them. “I was under the impression that he was blinded by the trauma inflicted by the policemen. Apparently, I was wrong.

“But I wasn’t wrong that they beat him up without cause; he was hospitalized and he’s entitled to substantial damages. I leave it to you as to what damages to give him.” Denton wasn’t really expecting much, but the all-white jury awarded Burns $10,000.

“Anyone who knows him will tell you he is a living refutation of every nasty lawyer joke ever told,” says Green, who adds that Denton is one of those rare lawyers who, when asked to represent someone, looks at the case and the person first, the potential fee second.

Even though they were best friends, Denton says that he was careful not to make presumptions about his relationship to Sawyer, and offered advice only when asked.

“We had an understanding,” says Denton. “He recognized, as did I, from reading the newspapers, that I was supposedly the fix man, the bagman, the hatchet man. So we had this arrangement. If I ever wrote him a letter recommending anything, he was not to pay any attention to it. If it was something I really considered important, I would call him. So I could write letters for people, recommending them for this or that, and give them copies, and if he wanted to make the appointment, that was fine, but it wasn’t my suggestion.”

“He isn’t a Sawyer man,” said Sawyer, “he’s his own man.” Sawyer learned this firsthand.

Once, Sawyer asked Denton for an opinion and the answer irked the governor. “Oh, Grant, I’m so sorry,” said Denton, his voice oozing sarcasm. “I didn’t know you wanted me to be a yes man. But I can do it if you want.” Sawyer sheepishly said, “No, Ralph, I don’t need another yes man. I have plenty of those already.”

One of Denton’s greatest frustrations was his failure to beat fellow Democrat Walter S. Baring for Congress. First elected in 1948 as a Truman man, Baring kept moving further to the right until by the 1960s, his power base was almost exclusively in the ultra-conservative rural counties.

“He kept in very close touch with his constituents and paid a great deal of attention to their needs. He learned that from Pat McCarran. He tried to take care of their problems as best he could; and if you can’t do it, you write to them and tell them the dirty bastards in the executive branch won’t do what we want them to do.”

In the 1964 congressional race, Baring prevailed, mostly because he opposed the Civil Rights Act. Denton challenged him again in 1966 and was the favorite. The Las Vegas Review-Journal called him “The Ideal Candidate.” Of the 124 Las Vegas precincts, Denton won 102. But Baring took the rural counties and the nomination.

In April of 1963, Sawyer named Denton to the Clark County Commission, and he was immediately corrupted. “I don’t think I was alone, but upon reflection, I terribly abused the comp privileges. The fact never occurred to me that they were trying to buy influence.”

He learned differently. When Interstate 15 had been completed, an exit was at Flamingo Road. Major Riddle, Dunes Hotel operator, asked the Clark County Commission to rename it Dunes Road along its entire length.

Denton saw the change as pointless, and a nuisance for businesses along Flamingo Road. The vote went 3-2 against the change.

“And I earned, as a result of that, the undying enmity of Major Riddle,” says Denton. Riddle complained bitterly to local banker E. Parry Thomas of Denton’s treachery. Thomas later told Denton about the conversation.

“He told me how upset Riddle was with me, after as nice as he’d been to me and all the meals they’d given me and all the shows I’d seen, that I would vote against him.”

Denton also opposed county acquisition of the Winterwood Golf Course, in the Southeast valley.

“It wasn’t unusual in those days, for developers to build a golf course and use it as a enticement to sell their lots. But they didn’t want to get stuck with the golf course; they weren’t the big money-makers they are now.”

The developers offered to sell the golf course to the county at their cost, but the Winterwood development was in a flood channel, and too close to the sewage treatment plant. Denton consulted several real estate brokers and all agreed that the place, well, stunk. County Manager Robbins Cahill and the county recreation director recommended against it, but Denton was the only commissioner to vote against it.

“I thought it was wrong for the county to shill this subdivision,” says Denton. “I was really shocked that my four colleagues just rolled over and played dead.”

In 1974, at the urging of Sawyer, Denton filed as a candidate for governor. He did so reluctantly. “I’ve never sought public office just to hold office,” he remarked. But most pundits that year were sure that Democratic incumbent Mike O’Callaghan wouldn’t seek re-election as governor, but run for the U.S. Senate. Denton was persuaded that he was the best man to replace O’Callaghan.

“It was absolute sheer stupidity on my part to file for governor before Mike had made a public statement as to what he was going to do,” says Denton. He withdrew when O’Callaghan announced he would run once more.

“I haven’t done anything that warrants any special attention in the practice of law or anything else for that matter,” Denton shrugs. “I’ve just tried to be a good citizen.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full