Trump succeeds in remaking federal judiciary

WASHINGTON — Within an hour of the news that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia died suddenly in February 2016, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced the Senate would not vote on whomever President Barack Obama picked to replace the fallen conservative lion.

“The American people should have a say in the court’s direction” by choosing a side in the presidential election in November, McConnell said. “It is a president’s constitutional right to nominate a Supreme Court justice, and it is the Senate’s constitutional right to act as a check on the president and withhold its consent.”

Some four years later, some things have changed and others have not.

One thing that has changed is that McConnell has said that if a Supreme Court vacancy opens this year, he will work to fill it before the voters speak in November.

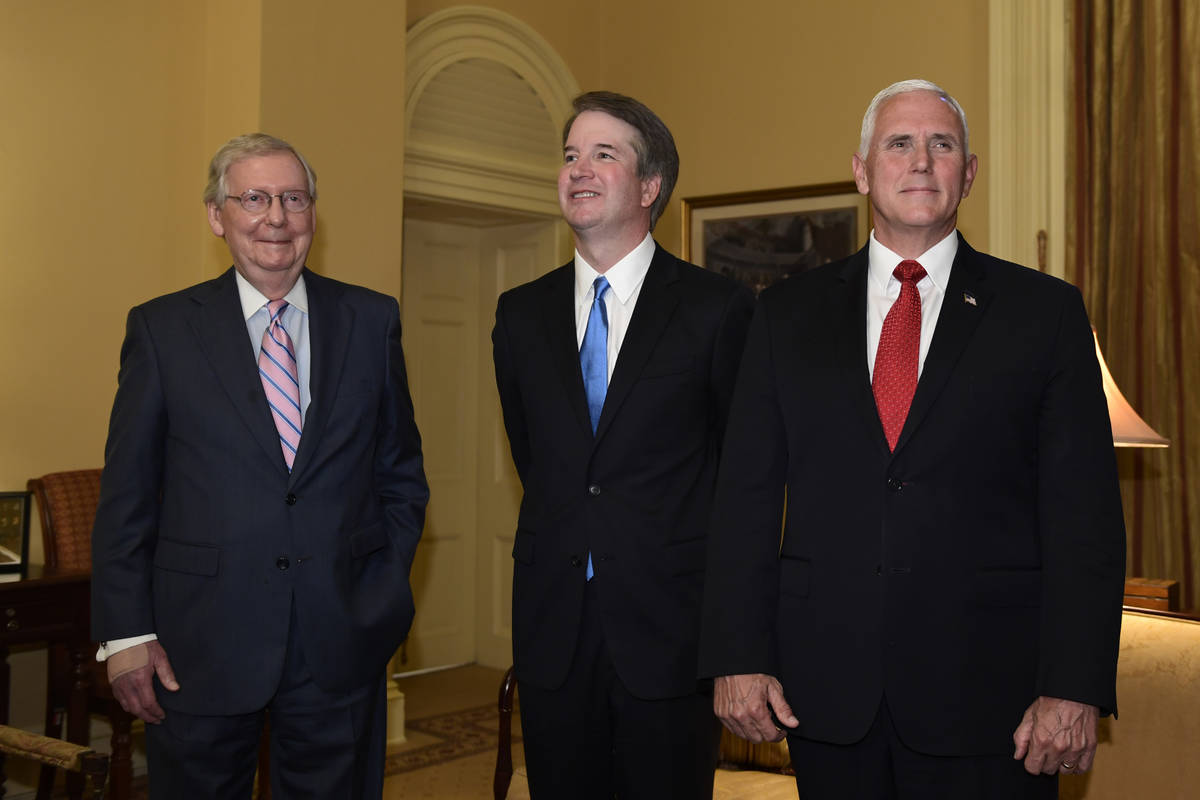

Another change: Donald Trump won the White House in 2016. The newly installed executive wasted no time making good on his promise to nominate conservatives to the high court. He delivered on that pledge when he successfully nominated Neil Gorsuch, then Brett Kavanaugh, to the Supreme Court.

One thing that has not changed: Beltway Democrats are enraged at Republicans’ ability to leverage their power to fill the nation’s benches with like-minded jurists. And given the GOP’s hold on the Senate and White House through 2020, they are jittery about the health of the four Supreme Court justices nominated by Democrats.

Winning over conservatives

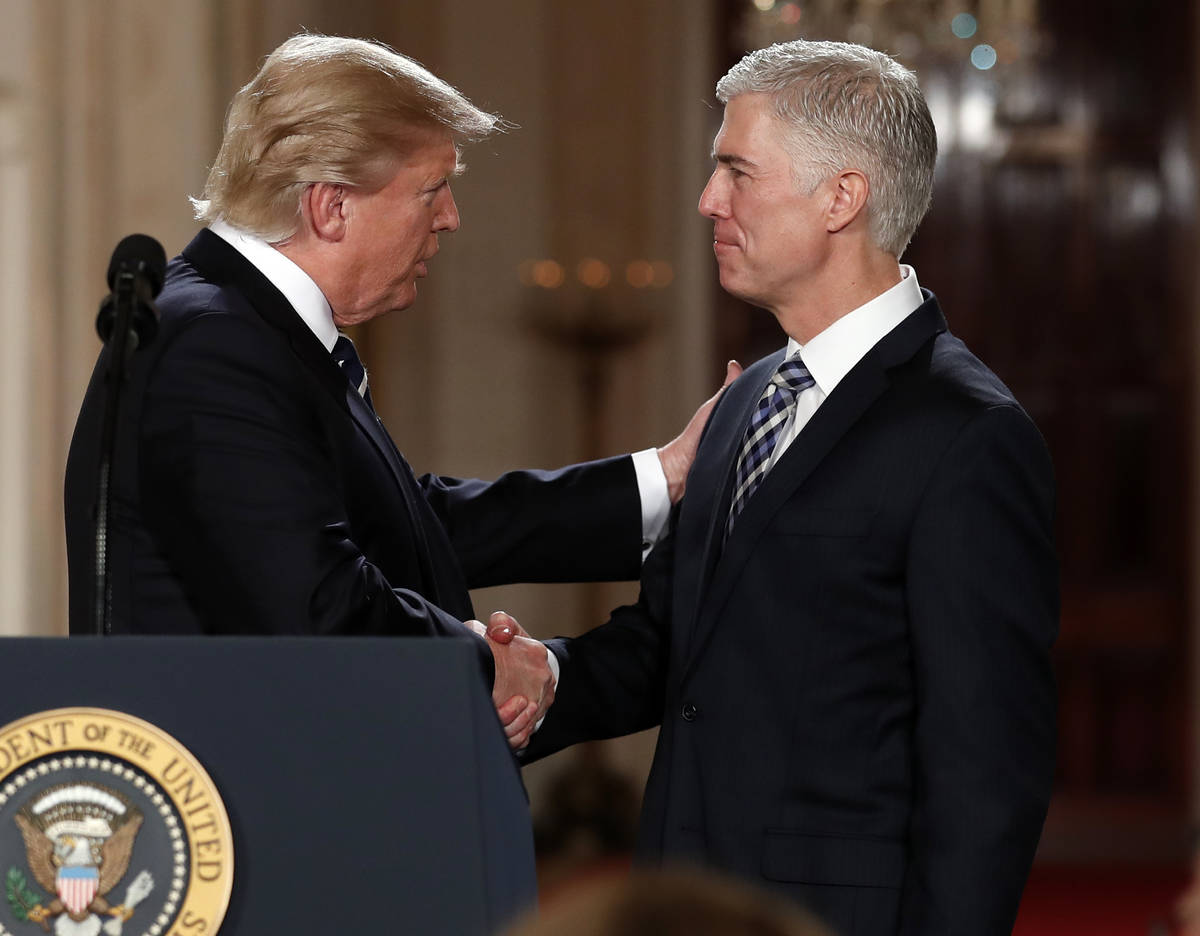

In 2016, Trump understood the best way to win over reluctant Republicans would be to assure them that he would restore the top court’s 5-4 conservative majority with justices who would be reliable votes in the decades to come. That’s why he released the names of potential Supreme Court justices during the campaign.

For 2020, Trump has another selling point: With Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, he has appointed 202 new federal District Court judges and 51 new appellate judges, according to Carrie Severino of the conservative Judicial Crisis Network.

It is the fruit of a concerted effort. Trump’s 51 appellate judges were confirmed at a rate nearly twice as fast as Obama’s, who appointed 55 appellate judges over eight years.

But as Severino sees it, the right had to mobilize to correct liberal judges “who are functioning more as politicians,” writing laws instead of interpreting them.

To the right, it’s a matter of survival. “Time and time again, you’ve seen Democratic-appointed federal judges being liberal activists in black robes rather than following the Constitution,” a senior administration official told the Review-Journal.

“They’re trying to consolidate political power through the judiciary that they don’t think they’ll be able to retain at the ballot box,” said Sam Berger of the Center for American Progress.

Court packing, slow-walking

Berger called the Trump-McConnell effort “a court packing plan” — a play on the term used for President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s bid to expand the Supreme Court to create a pro-New Deal majority.

The cooperation has successfully moved “hard-right ideologues” onto benches across the land. It is a feat that would not have been possible if McConnell had not delayed votes on open court seats.

Toward the end of Obama’s time in the Oval Office, noted University of Virginia law professor Saikrishna Prakash, McConnell engaged in “slow-walking” Obama’s court picks.

Slow-walking is a common exercise among partisans who want to stop a president from the other party from installing as many like-minded appellate and federal judges as possible on the bench toward the last years of a president’s term.

It’s a practice McConnell extended to the Supreme Court when Scalia died in 2016.

A month after McConnell announced the Senate would not vote on Obama’s unknown pick, Obama nominated Merrick Garland, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and a former federal prosecutor, as a moderate alternative to a more progressive figure likely to be nominated if, as expected, Hillary Clinton won in November.

As a senator, Obama voted against Chief Justice John Roberts and supported an unsuccessful filibuster to thwart the confirmation of Justice Samuel Alito.

Nonetheless, when he introduced Garland in the Rose Garden, Obama said, “I simply ask Republicans in the Senate to give him a fair hearing and then an up or down vote. If you don’t, then it will not only be an abdication of the Senate’s constitutional duty, it will indicate a process for nominating and confirming judges that is beyond repair. It will mean everything is subject to the most partisan of politics — everything.”

It’s highly unlikely that the Senate, with its 54-46 GOP majority at the time, would have confirmed Garland if there had been a floor vote on the Obama nominee, as Garland’s ascension would have shifted the Supreme Court’s balance from majority conservative justices to majority liberal justices.

But Democrats could have used a confirmation battle to apply pressure on GOP senators running for re-election.

The result, as the Center for American Progress’ Berger succinctly put it, “Merrick Garland is still a judge and not a justice.”

“As a matter of the original Constitution, I think Obama had it right and the Democrats had it right,” Prakash told the Review-Journal, because the Senate has an obligation to present its views to a president. But “the problem was they didn’t really believe what they said,” he said.

Indeed, Republicans had unearthed a 1992 quote uttered by former Vice President Joe Biden when he was in the Senate — that then-President George H.W. Bush should not nominate a Supreme Court justice if a vacancy occurred before the election. Such a vacancy never occurred, however, so Biden’s remark was never put into practice.

Might makes right

Perhaps the lesson is that each party will do what it needs to keep or gain judgeships. It’s not a matter of right and wrong as much as might making right.

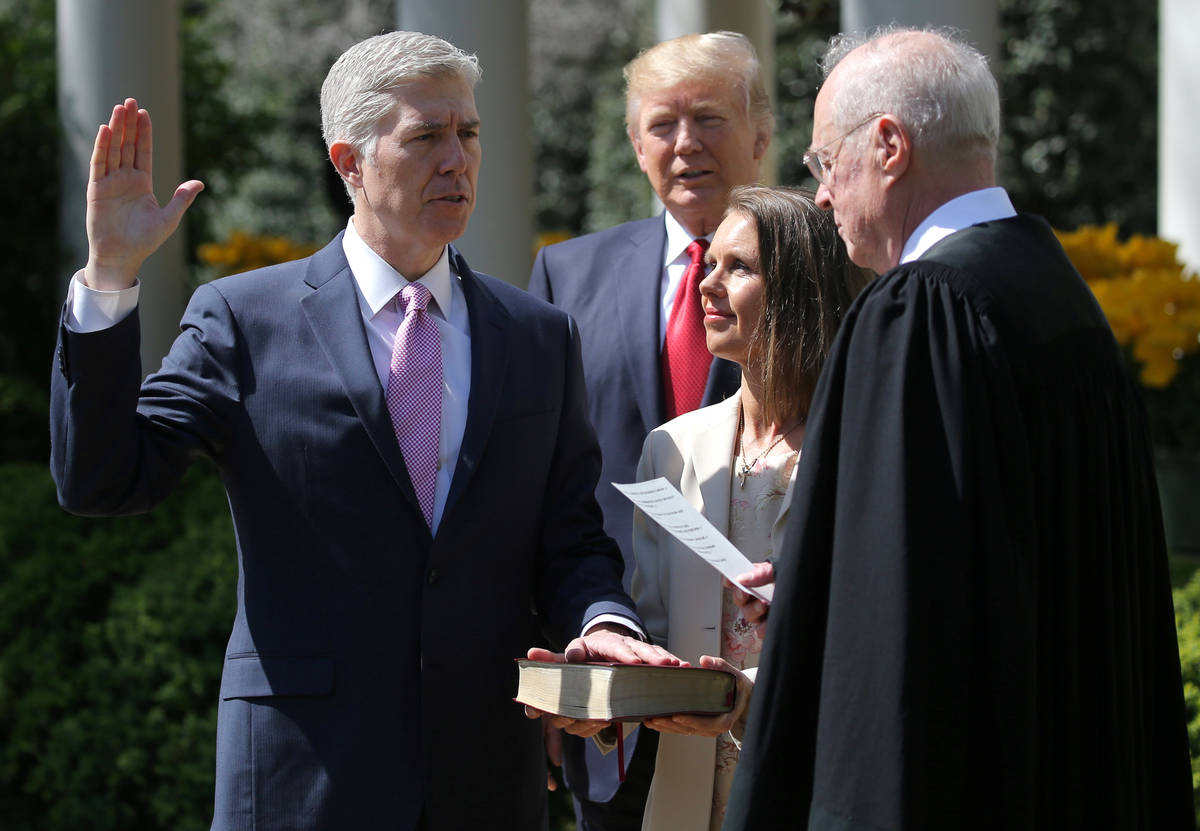

Promptly after taking the oath of office, Trump was able to nominate the highly credentialed Gorsuch, a favorite of the right-leaning Federalist Society, to the Scalia seat.

In retaliation for Garland, Democrats voted to block Gorsuch’s confirmation with a filibuster — a maneuver that required a supermajority of 60 votes to confirm Gorsuch.

McConnell struck back by exercising what Republicans called “the nuclear option.” The Senate voted along party lines — 52-48 — to eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court justices. Three Democrats from Trump-voting states then crossed party lines to put Gorsuch on the top court.

In ending the filibuster, Republicans argued that they simply were taking to its logical conclusion a 2013 rules change made under then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, who answered GOP obstruction by eliminating the filibuster for administration and judicial offices, but not Supreme Court nominees.

If Trump wins re-election in 2020 and Democrats take the Senate, Prakash offered, Senate Democrats “could very well do to Trump what Republicans did to Obama.”

That is, more “slow-walking,” this go-round of GOP judicial candidates.

The tit-for-tat escalation in eliminating rules that accommodate the minority party won’t end here.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., has argued that the filibuster must go for legislation as well because a gun-control bill cannot be passed by a supermajority.

But it is in federal courtrooms where Trump may have made a more lasting impression. There were 112 federal judicial vacancies when Trump took the oath of office. Trump had done nearly as much to shape courts in three years as former President Barack Obama did in eight years, wrote Ian Millhiser for the left-leaning Vox. Trump’s picks are “based solely on objective legal credentials, the average Trump appointee has a far more impressive resume than any past presidents’ nominees,” he wrote.

The pool of active and senior judges is now more than 1,000. Because the average age of Trump’s 200-plus judges is younger than 50, even if a Democrat wins the White House, it will be years, perhaps decades, before the influence of Trump’s judges wanes.

Another tool in the bench wars: blue slips. By tradition, senators have returned blue slips on circuit court nominees to signal their support for a nomination. The practice encouraged presidents to pick more moderate nominees acceptable to senators on both sides of the aisle.

In 2012, Reid nominated then-state District Judge Elissa Cadish to the federal bench. But then-Sen. Dean Heller refused to sign the blue slip, citing her position on a gun-control survey. Then-Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., would not hold a vote because of Heller’s missing signature.

But in 2017, then-Senate Judiciary Chairman Chuck Grassley said he would put nominees to a vote even if they did not have blue slips, another break with Senate tradition.

Last year, the Senate approved Lawrence VanDyke with 51 votes to a seat on the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals though neither of Nevada’s two Democratic senators — Catherine Cortez Masto or Jacky Rosen — returned his blue slip. The former solicitor general of both Nevada and Montana received a “not qualified” rating by the American Bar Association.

Severino, who went to Harvard Law School with VanDyke, said that “you couldn’t ask for a better lawyer or a man of more exemplary character.”

Changing the balance

Trump’s picks already have moved the balance of power in the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, known on the right as the “nutty Ninth” because of a history of liberal rulings. Democrats had enjoyed an 11-judge edge in the circuit, but now it has 16 active judges nominated by Democrats and 13 active judges nominated by Republicans.

Many decisions issued by the 9th Circuit are written by three-judge panels. With a more ideologically balanced makeup, Severino predicted fewer decisions destined to be overturned by the Supreme Court and fewer nationwide injunctions that expand a ruling by one judge or a three-judge panel that apply to the entire country.

In February, a federal judge in North Carolina blocked a Trump policy that makes it harder for undocumented immigrants to stay in the country after their legal status runs out. That same month, two judges on the 9th Circuit blocked Trump’s asylum rules on the grounds that the rules do harm outside the circuit.

Some Supreme Court justices have voiced their issues with the practice. “By their nature, universal injunctions tend to force judges into making rushed, high-stakes, low-information decisions,” Gorsuch and Justice Clarence Thomas opined recently.

“The one thing that’s really changed but comes into sharper focus is just how central confirming judges is over everything else, including responding to the (COVID-19) pandemic,” Berger said.

Berger noted that the Senate continues to work on judge confirmations as COVID-19 has brought death and high unemployment rates.

“Rather than considering bills to help people, they’re spending their time trying to confirm judges. And it’s pretty shocking when you think about it,” Berger said.

That was then

As for current Judiciary Committee Chairman Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., he has changed his mind about giving the voters a chance to chime in on a Supreme Court vacancy during an election year. In 2016, he said he was for it.

Graham told “Full Court Press” host Greta Van Susteren recently, “Merrick Garland was a different situation. You had the president of one party nominating, and you had the Senate in the hands of the other party. A situation where you’ve got them both would be different. I don’t want to speculate, but I think appointing judges is a high priority for me in 2020.”

While think-tank scholars talk about the need for apolitical judges, Trump showed his disdain for the notion when he dismissed a ruling against his asylum restrictions as the work of an “Obama judge.”

Chief Justice John Roberts countered, “We do not have Obama judges or Trump judges, Bush judges or Clinton judges. What we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best” to do right by those who appear before them.

Practically no one else in Washington believes that.

^

Contact Debra J. Saunders at dsaunders@reviewjournal.com or 202-662-7391. Follow @DebraJSaunders on Twitter.