Reasons for Democrats’ iron rule of Clark County Commission cover many fronts

It happened, again.

In an election considered fertile for political outsiders — a year when businessman and former reality TV star Donald Trump upset political behemoth Hillary Clinton in the race for President — all four incumbent Democrats on the Clark County Commission easily turned aside Republican opponents.

Each Democrat won re-election by more than 14 points. In one case, it was closer to 60 points.

This type of blue sweep has become typical in Clark County, home to more than 70 percent of Nevada’s population.

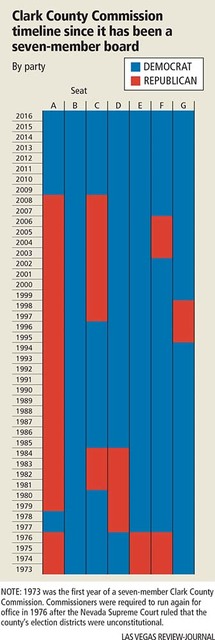

Here, voters have not elected a Republican to the County Commission since 2004.

So, what’s holding the GOP back?

PARTISAN RACE

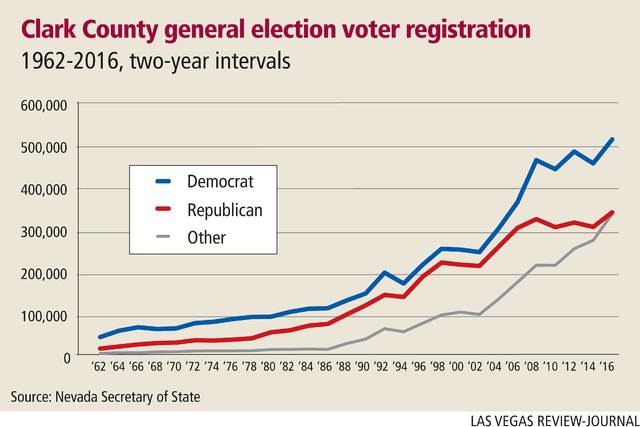

“It all starts with voter registration,” said Chris Miller, chairman of the Clark County Democratic Party. “In every one of those seven (County Commission) districts we have an advantage of there being more registered Democrats than Republicans.”

Throughout the county, registered Democratic voters hold the majority over registered Republicans, about 510,000 to 337,000.

The largest gap is in District D, which includes North Las Vegas, where there are more than four times the number of registered, active Democratic voters than Republicans.

And because commission elections are partisan races, having a D or R next to a candidate’s name means a lot.

“A lot of people, especially in a presidential year, vote a straight party ticket,” said Bruce Woodbury, an attorney, Republican and one of the commission’s longest serving members, from 1981 until 2009.

For Woodbury and other Republicans, such a wide disparity in voter registration numbers is enough to call for the end of partisan elections for local offices.

“I just think for the future, you would get more people willing to run for office if they didn’t have to worry about who had party registration plurality in their districts,” Woodbury said.

During the 78th Session of the Nevada Legislature in 2015, a bill to make the commission nonpartisan failed in the Assembly. No Democratic Assembly members voted in favor of the bill, which would have also effected other county elected offices including district attorney, treasurer and clerk.

Assemblyman Stephen Silberkraus, a Republican who authored the bill in 2015, has filed a bill draft request for the upcoming legislative session early next year. But after Democrats reclaimed control of both houses of the Nevada Legislature this week — including unseating Silberkraus — the proposal seems less of a possibility.

David Damore, a political science professor at UNLV who specializes in campaigns and elections, argued that removing the D’s and R’s could do more harm than good in local, down-ballot races, where voters typically have limited knowledge about candidates.

“It’s a useful cue … having that party label next to the name lets them have some inference on how the candidates would behave in office,” he said.

Damore added he believes the current commissioners bring a “diversity of opinions” to local government, pointing to the recent clash of ideals between Steve Sisolak and Chris Giunchigliani on whether a $1.9 billion NFL stadium should be partially funded by the public.

“Just because they’re in the same party doesn’t mean they’re always on the same page,” Damore said. “The Democrats fight on there. It’s not all unified. You see tension between them.”

Still, others believe a change is needed. Jordan Ross, whip for the Clark County Republican Party and a whip for the Nevada Republican Party, pointed to the county’s nonpartisan municipal elections as a “model that works” for giving Republicans a fighting chance at getting into local office.

“When people go to the ballots they’re not going to see Republicans or Democrats, they’re going to see the individual candidates,” he said. “It’s going to continue to be an enormous challenge to fundraise for Republican candidates for county commissioner as long as it remains a partisan race.”

‘MONEY MATTERS’

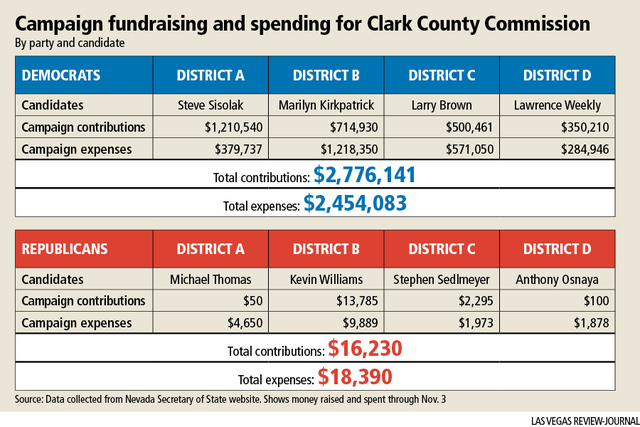

When it comes to campaign finances, the difference between parties is staggering.

As of Nov. 3, the four Democratic candidates running for County Commission had each received hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions, totaling $2.776 million.

That was 171 times more than the total amount raised by the four Republican candidates, all political novices and relatively unknown.

The vast gap in fundraising doesn’t surprise Damore. He said incumbency and name recognition are among the biggest barriers working against Republicans in County Commission races.

“It’s an expectations game. If people think the incumbents are going to win then that’s who they’re going to back with their money,” he said.

For Woodbury, it’s simple: “Money matters.”

“It makes a big difference. You’re able to afford signs and mailers and fliers, radio ads. If you want to go that far, TV ads. You’re able to hire consultants,” he said.

“It’s no different than any other election.”

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

The 2018 elections may hold the best chance Republicans have at winning a County Commission seat in years, according to Woodbury and Michael Green, an associate professor of history at UNLV and county resident for almost five decades.

Two Democratic incumbents — Susan Brager and Chris Giunchigliani — will be termed out.

In District G, Commissioner Mary Beth Scow will run for a third term after a narrow victory decided by roughly 1,000 votes in 2014.

“In (Brager and Scow’s) districts, there’s a Democrat plurality, but not overwhelmingly,” Woodbury said. “In Nevada the Democrats turn out in big numbers in presidential election years, not so much in nonpresidential election years.”

Green theorized “a good, business-oriented candidate who’s a political novice and takes directions” could propel the Republicans to a local victory.

But he has doubts the party can recruit such a candidate for the race.

“The most appealing Republicans are going to look elsewhere, to run for the Legislature or just stay out,” he said.

Woodbury agreed.

“It would take a challenger with some name recognition in the community, a person who was able to raise money or would be a self-funded candidate, a very wealthy person,” he said.

“But usually those types don’t start at the County Commission.”

Contact Michael Scott Davidson at sdavidson@reviewjournal.com or 702-477-3861. Follow @davidsonlvrj on Twitter.