Water negotiators spar as time runs out to stabilize Colorado River

Two bitterly divided coalitions of Colorado River states took shots at one another Thursday at a Las Vegas conference, indicating that a unified front on how to update expiring operating guidelines is not in the basin’s near future.

At the second day of the Colorado River Water Users Association conference, the Bureau of Reclamation provided more details about its five proposed paths forward for post-2026 river operating guidelines. And both the Upper and Lower Basin states spoke openly about their frustrations in separate panels about talks that haven’t yielded compromises needed to sustain the system that provides water to more than 40 million people, including Las Vegas residents.

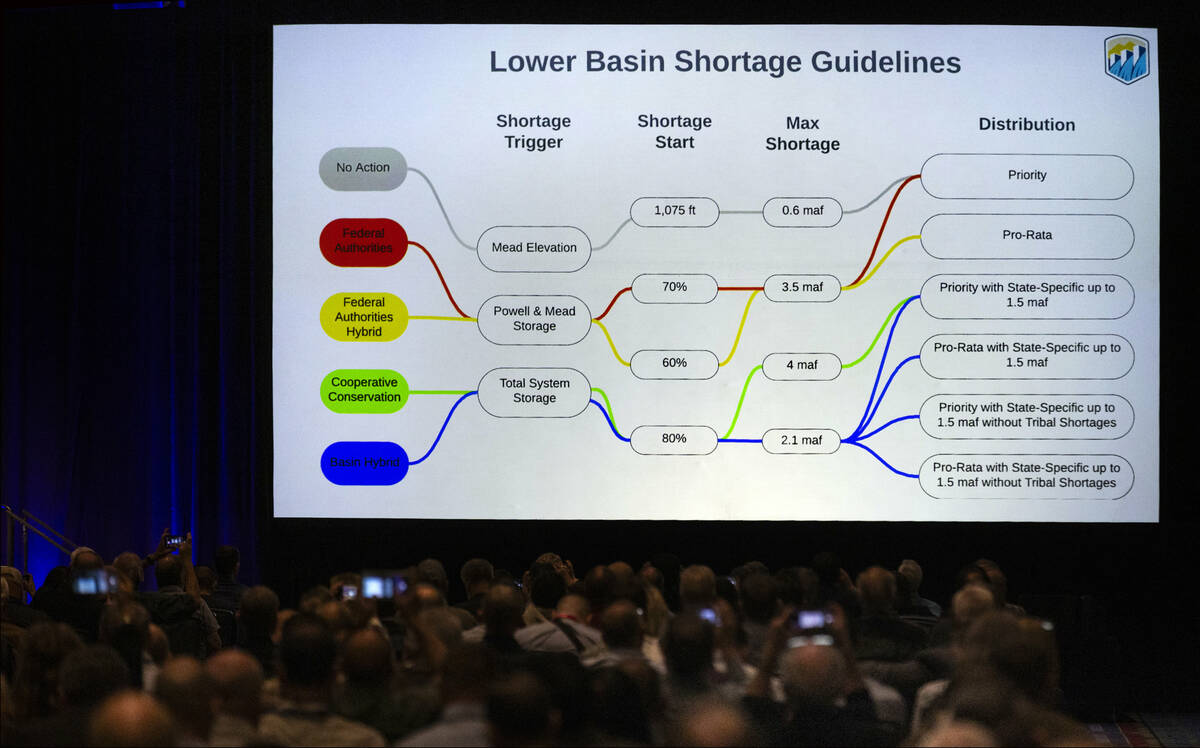

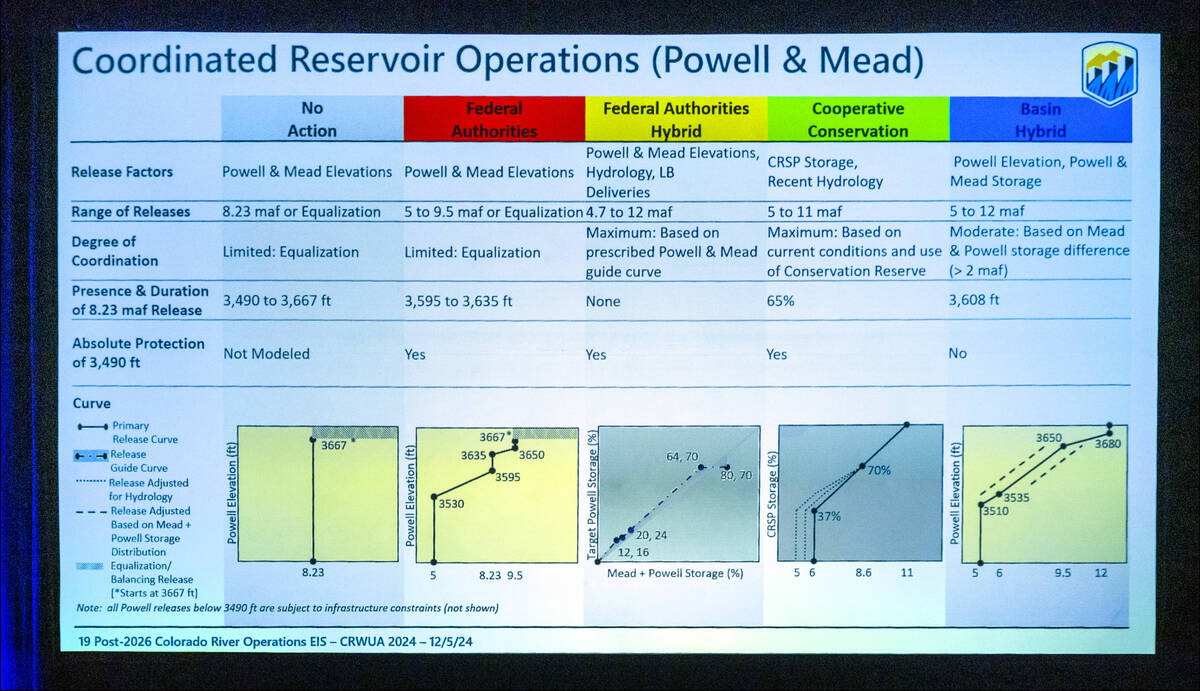

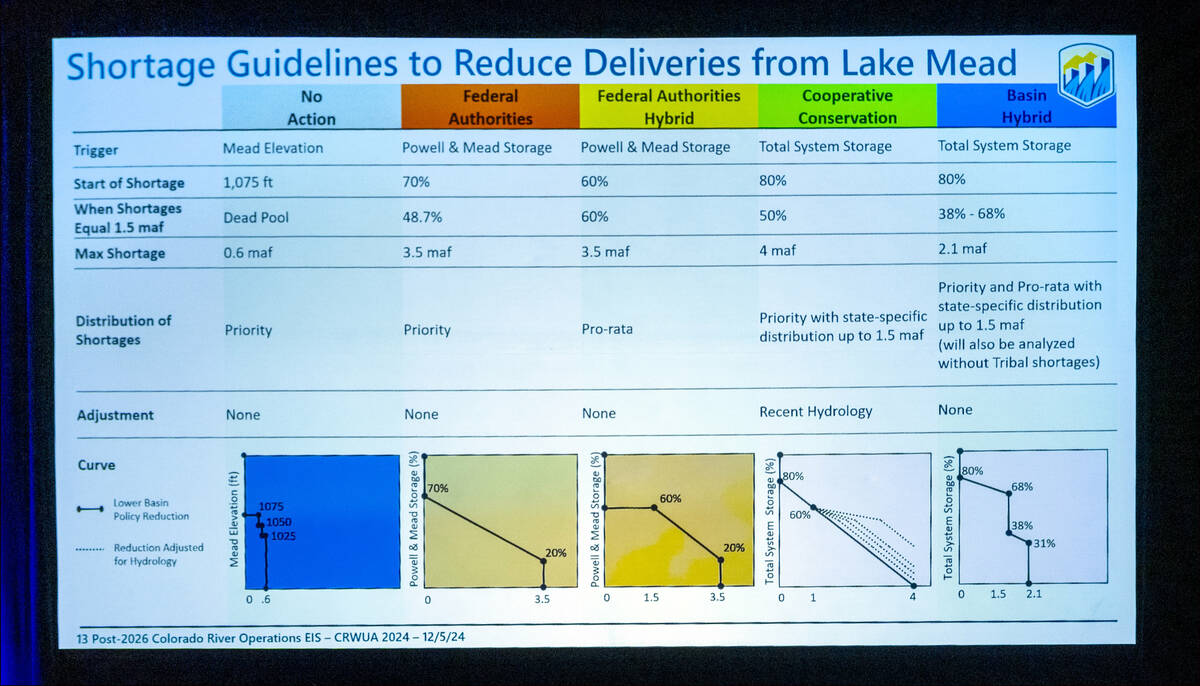

Rather than considering the competing proposals set forth by the Lower and Upper basins this year, the bureau put together a “Basin Hybrid” plan that regulators feel is the beginning of a compromise. Some have suggested that the disagreement could result in a costly Supreme Court case against the federal government.

“We’re in halftime here,” said Carly Jerla, the Bureau of Reclamation’s program manager over the interstate negotiations. “We need to be moving as a basin a lot faster in the second half than we did in our first.”

Jerla affirmed the agency’s intention of adopting guidelines by August 2026.

Why it matters for Nevada

The fate of the Colorado River is something that would directly affect Southern Nevada, a region of the state that sources 90 percent of its water from Lake Mead. Scientists say the river has faced unprecedented shortages in the 2020s, with less water available for use than ever because of climate change and historic overuse.

Thus, the need for sweeping changes to 2007 operating guidelines that will no longer apply in 2026.

Depending on how conversations proceed, the Lower Basin states of Nevada, California and Arizona could continue to bear the brunt of mandatory cuts to their allocations from the river. The Lower Basin has proposed basin-wide cuts should a shortage exceed 1.5 million acre-feet, the amount of water known as the “structural deficit” that the river loses to evaporation and transport.

The Upper Basin states of Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming have argued that declining snowpack and a lack of reservoir storage already set them back 1.2 million acre-feet. Northern states have floated putting more dams and reservoirs on the river that could, in total, store the equivalent of Nevada’s allotment from the river.

“We really need to understand that the enemy we’re battling right now is not the Upper Basin; it’s not the Lower Basin. It’s hydrology,” said Brandon Gebhart, Wyoming’s state engineer and Colorado River negotiator. “All of the rhetoric and other distractions going on right now are bulls—-. It needs to stop.”

Upper Basin negotiators pointed out that the conference could have been another chance for all seven states to meet, though that was not arranged.

In an interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal, Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke said the Upper Basin states decided they wanted to meet on Monday, not allowing sufficient time for preparation. Buschatzke said this is the first time all seven states haven’t met during the conference since he began attending in 2011.

Meetings between states are largely kept confidential, leaving little room for public oversight or scrutiny.

Despite the disputes, Nevada is still marching toward its goal of reducing water use to 86 gallons per person per day. That’s something the state has made gains in achieving every year, reaching a low in 2023 of 190,000 acre-feet of water used and not returned to Lake Mead.

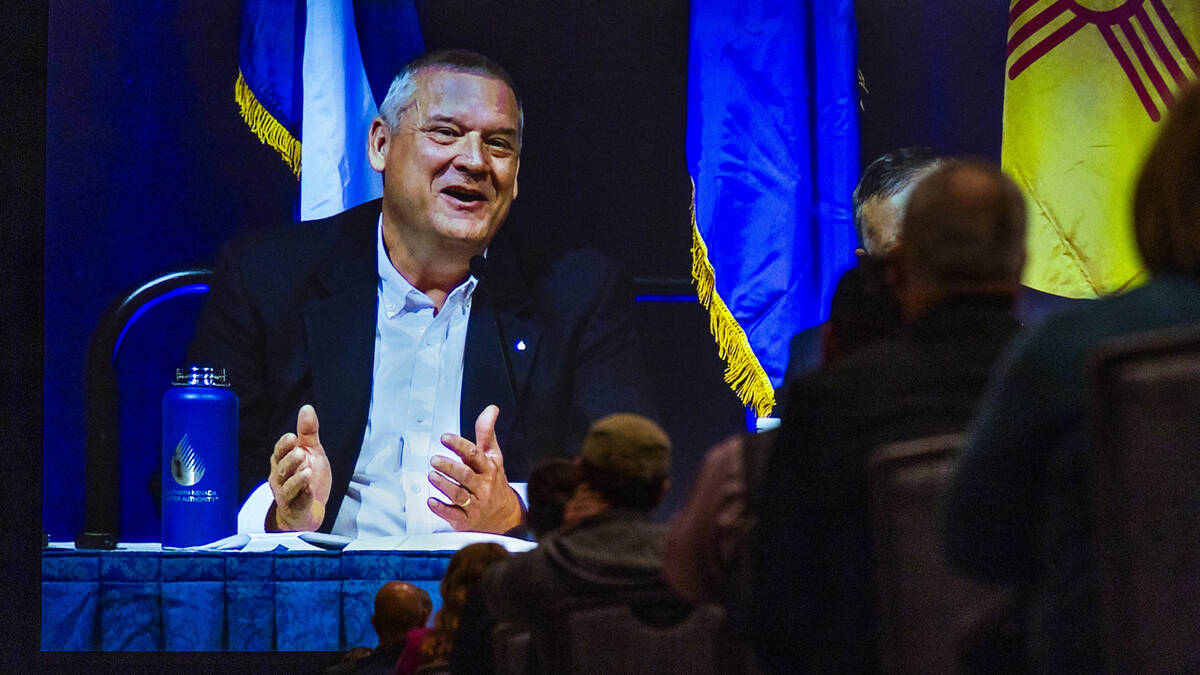

John Entsminger, Nevada’s representative on river issues and general manager of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, took a softer approach than other negotiators in his remarks.

“I want everybody from the Upper Basin to hear from Nevada: We believe compromise is possible,” he said. “We think it’s the first, second and third best option. But we need a dance partner, so let’s get back to the table and make this happen.”

States remain ambivalent on ‘Basin Hybrid’

Nevada and the Lower Basin haven’t offered much analysis of the Basin Hybrid plan.

Jerla, from the Bureau of Reclamation, provided more information about what such a plan might look like.

Like the Lower Basin’s proposal, the Basin Hybrid proposal would base shortages on the “total system,” meaning water stored in reservoirs other than Lake Mead and Lake Powell would be considered. That would lead to 200,000 acre-feet of Upper Basin conservation — something Buschatzke, of Arizona, said is essentially a cut without the name.

In a news conference, Upper Basin negotiators said they have requested that the Bureau of Reclamation provide more detailed modeling to see how the plan might work in practice.

When asked about the Basin Hybrid plan, Entsminger said there’s still a long way to go to seeing a consensus-based plan between both sides.

“I don’t think it performs as well as the Lower Basin proposal, but we haven’t had a chance to model it and compare that,” Entsminger told the Review-Journal. “They’re probably stressed less about the details of each individual proposal as they are about establishing the poles within which a preferred alternative can emerge.”

Bureau of Reclamation officials said the agency plans on releasing a more comprehensive analysis of all five federal proposals for post-2026 guidelines by the end of the year.

Contact Alan Halaly at ahalaly@reviewjournal.com. Follow @AlanHalaly on X and @alanhalaly.bsky.social on Bluesky.