Pension system perks cost taxpayers $23 million a year

Nevada governments are using the underfunded state pension system to boost the income of public employees.

The practice, which is legal but often based on decades-old or misused exemptions to the law, costs taxpayers at least $23 million a year in pension and salary, a Las Vegas Review-Journal investigation found.

An examination of pension data shows:

■ Over the past few years, hundreds of Clark County School District staff drew pensions and salaries based on an exemption that allows the extra payments for workers who fill jobs that are certified as “critical” and lack applicants. But after 143 of those authorizations expired, nearly half of the employees stayed in the jobs, despite losing the pension payments.

■ Some governments use the exemption to let workers collect pensions and salaries for political reasons or for positions they likely could fill without the financial incentive.

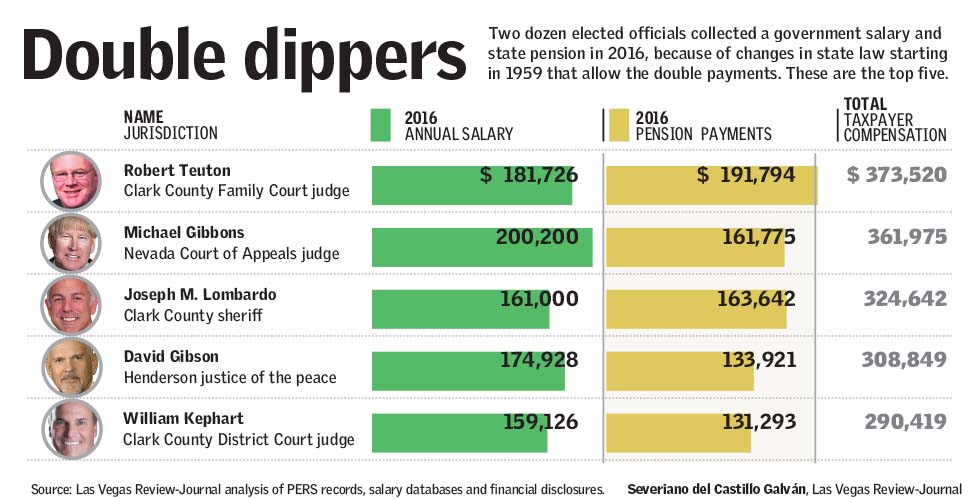

■ Two dozen elected officials collect salaries and pensions at the same time, including eight politicians who use the arrangement to make more than $250,000 a year.

■ There is little accountability or transparency in the system.

We don’t give them pensions so they can double dip. We give them pensions so they can retire.

Edward Zelinsky, professor at the Cardozo School of Law in New York

Edward Zelinsky, a professor who studies pensions at the Cardozo School of Law in New York, said the payments are a symptom of a system bloated with unnecessary expenses and perks.

“We don’t give them pensions so they can double dip,” he said. “We give them pensions so they can retire.”

Elected officials who collect retirement on top of a salary argue that they earned the pension payments and work hard for their current public salaries. They also say the additional pay does not cost the state more, because others would continue to be paid for those jobs if they left their elected positions to retire.

But the benefit creates an incentive for trained workers to retire and switch jobs as soon as they are eligible to leverage the extra pay.

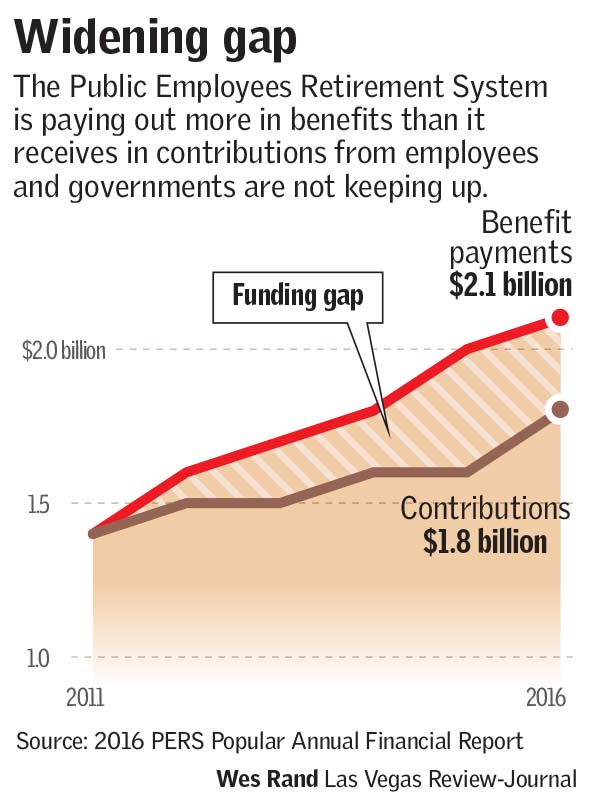

The costs of double dipping also add to the strains on a trust fund that some experts say is headed for insolvency.

The current returns on the fund’s investments are too low to maintain retiree benefits, said former state Assemblyman Randy Kirner, who tried to pass a bill to reform the system when he was in the Nevada Legislature.

“We will need a half-billion-dollar bailout or a billion-dollar bailout, and someone will have to come up with that number,” Kirner said. “That’s going to be the taxpayers.”

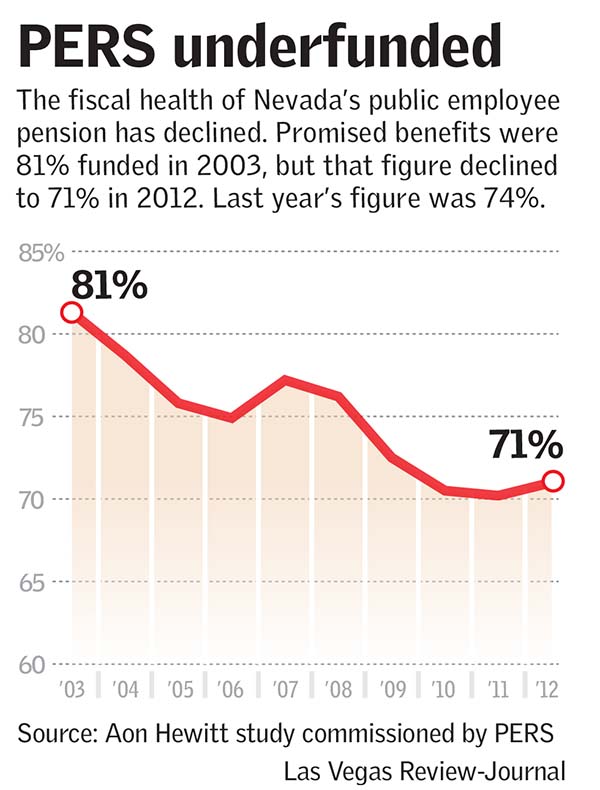

The plan’s 32-year average annual return is 9.4 percent, but in the last decade that dropped to 6.3 percent, pension records show. The fund paid $300 million more to recipients than it collected in contributions in 2016. The pension currently has enough money to meet about 74.1 percent of its obligations, figures show.

Pension fund executive officer Tina Leiss said the fund’s ability to pay future retirees is not a problem and the $38.5 billion account is set up to ensure that retirees get paid.

“The idea of a taxpayer bailout is not supported by any facts,” she said.

The pension agency commissioned a 2013 study that showed the account would be fully funded in 30 years. The study also noted that Nevada’s unfunded liability is about average for other state systems.

We will need a half billion dollar bailout or a billion dollar bailout and someone will have to come up with that number. That’s going to be the taxpayers.

Randy Kirner, former state Assemblyman

Unusually broad law

Most Nevada public retirees must suspend their pensions if they work more than part-time hours, but state law allows any elected official and anyone whose position is certified as critical by a government agency to collect a full-time salary and pension benefits from the Public Employees Retirement System.

The Review-Journal surveyed state pension plans nationwide. Of the 44 states that responded, only six made special provisions for all elected officials to collect pensions and salaries.

For positions deemed critical and hard to fill, only 10 states have such exemptions, and more than half of those are limited to specific categories, such as teachers or prison staff. Nevada allows governments to certify any position as critical if officials document a shortage of qualified candidates for the job.

Most private employers have phased out pensions, requiring workers to fund their own retirements through 401(k) savings that are not usually accessible until age 59½. Social Security beneficiaries who return to work but are not yet 66 years old receive sharply reduced benefits: They lose $1 for every $2 earned over about $16,000 a year. But many of Nevada’s double dippers retire in their mid-50s and then collect as much as 90 percent of their former salaries, along with a new five- or six-figure salary.

To get positions certified, Nevada governments must document the turnover history of the job, the number of open positions compared to qualified candidates, the length of time the position has been vacant and the agency’s recruiting efforts.

However, no one at the state or pension agency can protest or overturn the decision, no matter the justification.

The pension agency also has sought to keep basic information about recipients secret, fighting two separate lawsuits from organizations trying to obtain basic information such as retirees’ names and the agencies where they had worked.

The libertarian Nevada Policy Research Institute won a ruling in January from District Judge James Wilson for more information. But pension officials appealed, spending more than $177,000 to fight the lawsuits, records show.

Robert Fellner, a director at the institute, said the fights are inappropriate.

“It’s indefensible that PERS has publicly opposed transparency,” he said.

Chris Nielsen, general counsel at the agency, defended its spending on court cases.

“We need further clarity, and with all due respect to Judge Wilson, the District Court isn’t the final say in all of this,” he said.

Who collects a pension check? Search the list here and see who received the biggest checks in April.

Who collects a pension check? Search the list here and see who received the biggest checks in April.Big money for elected few

Many elected officials retired only after they were assured of having an elected position to collect a salary.

Michael P. Gibbons retired from his position as a District Court judge on Dec. 31, 2014, with a $160,000 state pension. Five days later, he took the oath for an appellate court job that pays more than $200,000 a year. Gibbons’ annual income now tops $360,000.

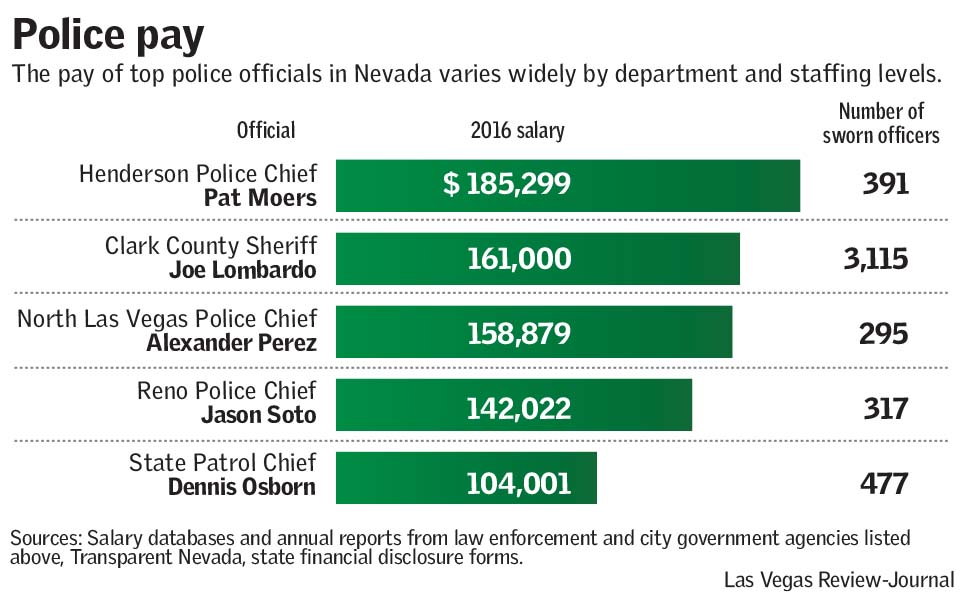

Clark County Sheriff Joseph Lombardo retired from his position as assistant sheriff at the Metropolitan Police Department after voters elected him to the agency’s top job in 2014. He collects nearly $325,000 a year in salary and pension, records show.

And Clark County Family Court Judge Robert Teuton retired from the district attorney’s office in 2008 after the governor appointed him to the bench. Teuton’s combined income is now more than $373,000 a year.

Public retirees often take jobs in other states or in the private sector to collect a pension and a new salary, but it is improper to use public funds for both payments, Zelinsky said.

“It’s deeply troubling, whether or not they’re elected officials, that you’re taking two salaries and that those are financed by the same taxpayers,” he said.

Officials point out that state law allows the payments.

“I had a very good career serving the residents of Clark County for 27.5 years, and I am being appropriately compensated after retiring from that job,” Lombardo said.

Teuton, the Family Court judge, would only issue a statement. “As a young attorney, I began serving our community as a Deputy District Attorney, prosecuting criminals and serving to protect the public,” he wrote. “I chose to forego the potential of a higher salary in private practice.”

Judge Gibbons said he earned his pension and salary by serving the public as a prosecutor and judge for decades. “I could have retired and just gone into private practice and made tremendously more,” he said.

Gibbons said a quirk in pension calculations would have reduced his survivor benefits if he didn’t retire, so he planned to leave office. Then Gov. Brian Sandoval appointed him to the newly formed appellate court. Gibbons also noted that his take-home pay is far less than $360,000 after taxes.

The “amount of federal income tax we have paid beginning in 2015, has dramatically increased,” he wrote in an email. “My net income from employment earnings, and retirement benefits (which are fully taxed as ordinary income), is much different than the gross income numbers that are commonly reported.”

Recruiting aid or pricey perk?

The Clark County School District relies on the use of pension funds as a job incentive more than any other agency in Nevada.

Of nearly 1,200 positions certified as critical in the state since 2001, more than half were at the school district, pension data show.

School officials and other local and state government leaders say they could not fill some teaching, police and even school bus driver openings without the retirement pay.

But when exemptions for 143 Clark County school positions expired after the 2009-10 school year, about 60 teachers, counselors and other staff chose to stay in the jobs without being able to collect pensions, raising questions about whether the perk was necessary.

“The Legislature created critical labor shortages for very valid reasons, but arguably it might be overused,” said Cheryl Blomstrom, interim president of the Nevada Taxpayers Association.

School district spokeswoman Melinda Malone said the district does not know why some teachers continued to work after the certifications for their positions expired.

“Just because some teachers chose to stay doesn’t mean they would have returned to teaching without the (labor shortage) incentive in the first place,” she wrote in an email statement.

The costs are significant.

Between 2001 and 2014, the pension agency paid $97 million in benefits to people who were working full-time for government agencies, Segal Consulting studies conducted for the pension agency show.

“We believe it is appropriate to assume that these retirees would not have retired had the (labor shortage) provision not been in place,” the study authors wrote.

Last year, the pension system paid at least $7 million in benefits to retirees who are in critical labor positions, and governments paid them an additional $9 million in salaries, a Review-Journal analysis found. Those figures are not complete, because pension officials do not release information that could be used to verify the agency from which recipients retired. About two dozen school district retirees contacted by the Review-Journal did not return calls or declined comment.

Officials point out that there are savings in labor shortage positions because the school district doesn’t have to pay retirement contributions for returning teachers.

Pension chief Leiss said her agency’s board opposed the labor shortage exemption. “Ultimately it is the Legislature’s purview to adopt what it thinks are the appropriate benefit provisions,” she said.

Clark County schools lobbied in favor of a law that made the temporary program permanent in 2015. Michael Gentry, the district’s chief recruitment officer, said it does not like using the critical exemption but often has no choice.

“We have done a good job reducing vacancies,” he said. “But as a stopgap measure the (exemption) makes phenomenal sense.”

Critical or political?

In 2012, Elko County Sheriff Jim Pitts had to replace his undersheriff, Rick Keema, after he failed to obtain police certification.

Instead of filling the position with a current staff member or recruiting outside candidates, Pitts asked the county board to certify the position as critical and hired Clair Morris, who had retired from the department in 2005. The position paid $92,700 in 2013, and the salary went up to $102,994 in 2015, records show. Morris also collected about $70,000 a year in pension benefits.

When Morris left last year, Pitts filled the job with another retiree, Ron Supp, who is paid about $90,000 a year and collects more than $92,000 in pension benefits for serving as undersheriff of the 66-officer department.

Pitts said he could not find qualified internal candidates who wanted the position, and he believed it would be unfair to appoint and bring a new hire to Elko with the risk of losing the job if Pitts did not win re-election.

“I have a couple of people in the department (who) don’t have the years in the (pension) system to take the chance of not having a job if I’m not re-elected,” he said.

Blomstrom, of the taxpayers association, said Pitts’ justification for adding pension pay to the salary is not what lawmakers intended.

“If that is indeed what happened, that is tough to defend,” she said.

Pitts said he will drop the practice in the future.

Fellner, of the NPRI, said lawmakers should prohibit double dipping.

“The Legislature should do what they expressly stated the purpose of (the pension system) was to do: Provide a reasonable base income for those who are no longer able to work,” he said.

Contact Arthur Kane at akane@reviewjournal.com. Follow @ArthurMKane on Twitter.