Nevada heroin overdose deaths have nearly tripled since 2010

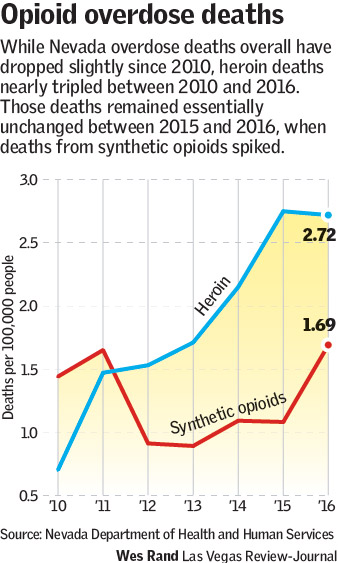

Opioid-related deaths in Nevada have decreased slightly since 2010, but the number of fatal heroin overdoses has nearly tripled since then, according to state data presented Thursday.

But that pattern appears to be changing as well, as heroin-related deaths remained unchanged between 2015 and 2016 while deaths from synthetic opioids, including the super-potent painkiller fentanyl, rose by 56 percent.

“I think the data is definitely evidence that there’s a shift,” Kyra Morgan, chief biostatistician of the Nevada Department of Health and Human Services, said Thursday in a presentation to roughly 45 state and local officials gathered in Reno and Las Vegas.

The data were presented at the first meeting of a new group organized by Attorney General Adam Laxalt. The Statewide Partnership on the Opioid Crisis was formed to increase sharing of information about the epidemic among state and local public health and law enforcement agencies.

“What we’re trying to address here is how as a state we can come together from an information-gathering perspective,” Laxalt said in explaining the group’s purpose. While many state and local agencies collect data on opioid use, overdose deaths and prescriptions, much of it isn’t shared with other agencies.

That prevents public health officials from quickly assessing the data and responding in a way that could prevent unnecessary deaths, said Terry Kerns, the attorney general’s substance abuse law enforcement coordinator.

“If we had a spike in scarlet fever in Carson City, we’d know that very quickly, and the state can coordinate and come up with a response,” said Laxalt, who has declared his candidacy for governor. “We don’t have anything like that in the state for opioids.”

Obstacles in data collection, sharing

Obstacles to statewide collection and sharing of data outlined in the meeting included the underreporting of opioid deaths in rural counties. In rural areas, sheriffs often double as the county coroner, Washoe County Coroner Laura Knight said. They can generally run their own toxicology screening — though they don’t have the forensic pathology background to interpret the results — and often forgo sending bodies to urban coroner’s offices in Washoe and Clark counties because it’s costly.

It’s a national problem, Morgan said, and she is not sure it’s solvable without more funding.

“We’ve been in conversations with other states, so I guess if we’re all going to be wrong, we’ll be wrong together,” she said.

Knight and Clark County Coroner John Fudenberg said they’re open to training rural sheriff-coroners to improve reporting of cases of potential overdoses.

Officials also brainstormed ways to share data between health care providers, such as hospitals and emergency responders, and public health offices.

One legal roadblock raised was HIPAA, the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which generally prohibits the sharing of patients’ confidential health information.

But Linda Anderson, chief deputy attorney general, said HIPAA has built-in exceptions to allow for the release of information for the use of public health surveillance.

Other laws, such as the Family Education Rights and Privacy Act, which protects student records, and 42 CFR Part 2, which makes records of substance use disorder patients confidential, create hurdles to data sharing too.

It’s up to legal counsel for health providers to discuss how that release of data is handled to protect individuals, Anderson said.

‘It’s going to take the community’

Kerns, the AG’s opioid coordinator, was appointed in October to help streamline state opioid data so it’s readily available for public health officials. She hopes meetings with the working group and other organizations create a platform for discussing what data already exist and how to share it in near real-time.

“What I’m concerned about is trying to get data on what is the current picture going on within the counties, within the state,” she said. “Data tells you a lot, but I’d like to be able to know this week what’s going on. I don’t feel like I have a grasp on that.”

Kerns is looking into creating a near-real-time opioid mapping system that would show where overdoses occur, whether the incident was fatal and whether naloxone, the opioid antidote, was administered.

If that information could be entered into the system, either by a first responder or automatically with the use of electronic patient records, that would help officials pinpoint spikes in distribution or areas seeing increased opioid use, which could enable officials to respond quickly to prevent deaths, she said.

According to Kerns, some emergency medical responders already collect that data, but it just hasn’t been consolidated and analyzed.

“It’s a multi-factorial problem,” Kerns said. “It’s going to take the community to try to fix the problem.”

Contact Jessie Bekker at jbekker@reviewjournal.com or 702-380-4563. Follow @jessiebekks on Twitter.

Ongoing efforts to combat opioid misuse and overprescription

The Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act passed in 2015, which expanded access to naloxone and provided immunity for providers using the drug for life-saving efforts.

Nevada Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval convened a summit in 2016 to address the role of prescription drugs in the state’s opioid problem.

Laxalt’s office is working with other attorney generals to investigate whether manufacturers nationwide unlawfully sold and marketed opioids. The investigation, launched in June, is still ongoing.

On Jan. 1, a new law went into effect, providing guildines for prescribers issuing controlled substances for pain. The law has created confusion amongst doctors, many of whom feel the law is too restrictive.

Prescribers are waiting for the state’s licensing boards to reveal finalized disciplinary rules related to the law.