Jobs, architectural bravado back with structure by Hoover Dam

Hoover Dam is an engineering marvel, its construction, the stuff of lore. The dam was built during the Great Depression from 1931 to 1935, drawing more than 5,000 workers to the cauldron of the Nevada desert. The construction project provided much needed jobs for an out-of-work country, while opening the West to new development with water and power.

It’s powerfully ironic then, that as the country faces its worst economic slump perhaps since the Depression, that sense of engineering bravado and big-time building is back. This time with a monumental bridge 1,500 feet downstream from the Hoover Dam. Its official name is the “Mike O’Callaghan-Pat Tillman Memorial Bridge,” named after former Nevada Gov. Mike O’Callaghan (1971-79) and professional football star-turned-soldier Pat Tillman who died during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan.

“It’s a well-known project in the engineering community,” said Khaled Mahmoud, chairman of the New York City-based Bridge Engineering Association. “It’s the longest concrete single arch bridge in North America, and the fourth-longest in the world.”

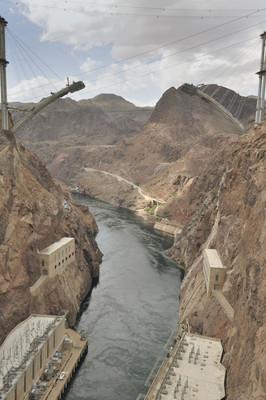

The sleek structure stretches across Black Canyon in a single span, soaring 890 feet above the Colorado River. The concrete-and-steel composite bridge, which measures 88 feet wide and 1,960 feet long, is significant because of its commercial importance and proximity to the dam.

But there is more to the $240 million project than meets the eye. Like Hoover Dam, which required nitty-gritty foundation work and diversion tunnels, the bridge similarly entails complicated but less visible site construction. The components, though less spectacular, play crucial roles in the overall bridge program.

For example, there are new four-lane roadways at each bridge end that tie into U.S. Highway 93. The 1.8-mile-long Arizona approach, which finished in October 2004, has a small 900-foot-long bridge that spans a 200-foot-deep ravine on the east side of Sugarloaf Mountain. It also has a new intersection at the Hoover Dam Access and Kingman Wash roads. The 2.11-mile Nevada approach, meanwhile, finished in October 2005, roughly two months ahead of schedule. It consists of six new bridges over rocky terrain that includes a 463-foot-long, steel-girder structure over a 160-foot-deep gulch. There is also a new four-lane highway alignment and a new traffic interchange at U.S. 93 near the Hacienda Casino. R.E. Monks Construction Inc. of Fountain Hills, Ariz., built the Arizona half with Chino Valley, Ariz.-based Vastco Inc. Edward Kraemer & Sons Inc., of Plain, Wis., did the Nevada side.

Eight large steel-lattice power towers carrying 230-kilovolt and 440-kilovolt electrical lines were also moved away from the bridge path. The $9.6 million job was completed by Kansas City, Mo.-based Par Electrical Contractors in 2003.

“Collectively, the project is 85 percent complete, including earthwork, paving and utility lines,” said Dave Zanetell, project manager for the Federal Highway Administration’s Central Lands Highway Division. “The center span of the bridge will finish in October, with final completion about a year later.”

Talk of an eventual alternate route over the dam dates back to the 1960s. Traffic often congests U.S. Highway 93, which now runs over the dam’s crest. The route also has switchbacks and abrupt inclines that create safety concerns. The two-lane roadway, a key route in the North America Free Trade Agreement between the United States, Mexico and Canada, sees 17,000 vehicles daily. It has also been identified as a high-priority corridor in the National Highway System Designation Act of 1995, and it’s a part of the Canamex corridor linking Canada to Mexico.

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, security for the nation’s infrastructure and monuments was increased. Truck traffic has since been diverted 23 miles away from the dam, costing consumers some $30 million annually. Other commercial four-lane routes add an additional 250 miles.

“Right now, our guys cannot go over the dam. They have to go through Laughlin instead,” said Paul Enos, CEO of the Nevada Motor Transport Association, a Sparks-based industry trade group. “The bridge is important for more efficiently moving commerce and goods throughout the West. It benefits everybody. There is nothing in society today that trucks don’t move, including clothes, food and medicine.”

Construction of the bridge will create 1,200 direct and indirect jobs; the economic impact of not building it is $100 million annually, the administration estimates. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is allocating money for new construction to re-energize the economy. “Shovel-ready” projects have recently taken center stage. But not all construction is the same.

“More complicated construction, like building a new bridge, has a higher rate of economic return,” said Edward Sullivan, chief economist for the Portland Cement Association, a Skokie, Ill.-based industry trade group. “For every dollar spent, you get 16 percent more jobs created in new bridge construction.”

The Hoover Dam Bridge is as big and complicated as it gets. A joint-venture led by Obayashi Corp., San Francisco, with PSM Construction USA Inc. of Brisbane, Calif., won the contract in 2004 with a $114 million low bid. Its proposed cableway bridge erection method helped it cinch the deal. The contractor is using four 330-foot-tall steel towers, two pairs on each side of the Black Canyon, with 2,500-foot-long, 3-inch-diameter cableways strung in between. Bridge segments are moved into place using trolleys attached to cables, or “high lines” as workers call them. The system can carry 50 tons of building materials at speeds of up to 400 feet per minute. A similar system was used during construction of Hoover Dam. It’s the most practical way to move things over the canyon’s treacherous terrain and sheer drop-offs. It’s something like the arcade game in which a player maneuvers a mechanical claw over a prize, lifts it, and drops it into an opening.

“Cableways aren’t a common thing to use in bridge construction, but you’re dealing with a construction site that is 800 feet about water level,” said Mahmoud, who also serves as president of Bridge Technology Consulting, a New York City-based company.

In September 2006, trouble struck the bridge construction site. The cableways collapsed under 55 mile-per-hour winds, bringing construction to a standstill. The incident delayed bridge construction by a year. Both the owner and contractor declined to comment further on what went wrong.

But Obaysahi/PSM faces $8,000 a day in late fines after 1,271 working days, which could amount to $5 million in late penalties. The high lines were a 42-year-old system refurbished for the project by Coraopolis, Pa.-based American Bridge Co. It was originally built by manufacturer Skagit in 1964, and worked on West Virginia’s New River Gorge Bridge through 1977. It was used on other jobs before being decommissioned in 1988. A new cableway system has since been designed and built specifically for the Hoover Dam Bridge. It’s in use now. The project has found its stride again, with about 150 crafts workers on site.

“I think (the bridge) is going to have a huge impact,” said Ray Bacon, executive director of the Nevada Manufacturers Association, a Carson City-based industry trade group. “In general, Nevada has more and more truck traffic that ships from the (Interstate) 15 corridor and moves toward U.S. 93.”

The bridge opens U.S. 93 as a major corridor in the movement of manufactured materials; trucks now deliver products and goods to 80 percent of all U.S. communities.

Rising fuel costs, growing gridlock and increased emissions standards could force more trucks to abandon Interstate 5 in California in favor of U.S. 93, which is characterized by long straight stretches with few steep grades.

“The new bridge will eliminate the sharp turns, narrow roadways, inadequate shoulders and low travel speeds of the existing travel route,” Zanetell said. “This is really a historic project that has been a long time in the making.”

Contact reporter Tony Illia at tonyillia @aol.com or 702-303-5699.