Lingering regret led to Sandoval’s run as Nevada governor

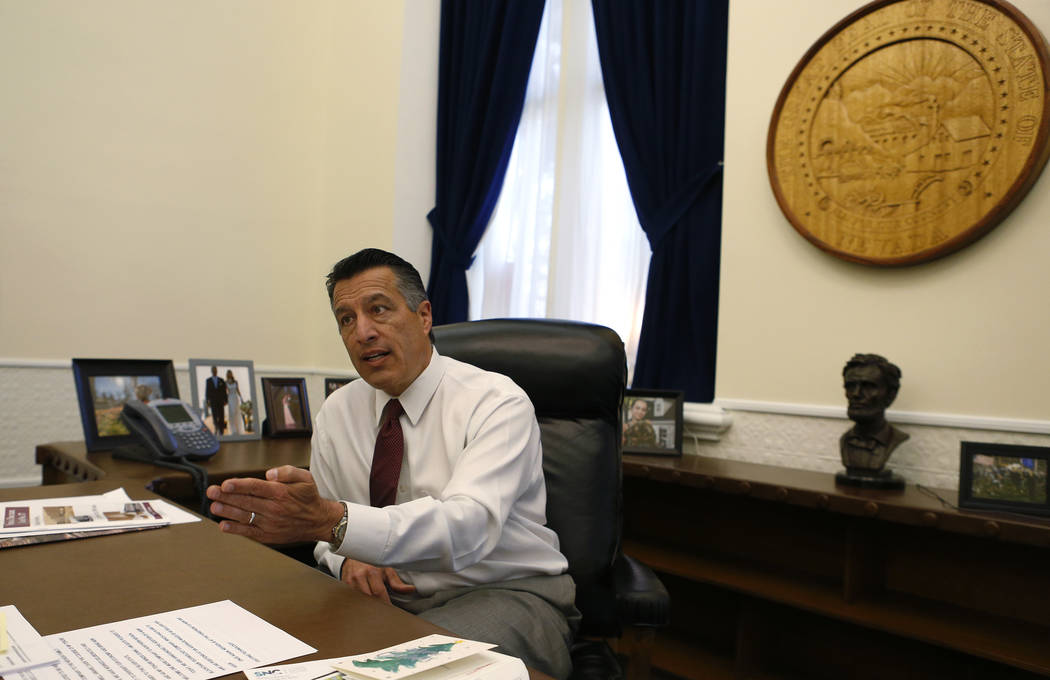

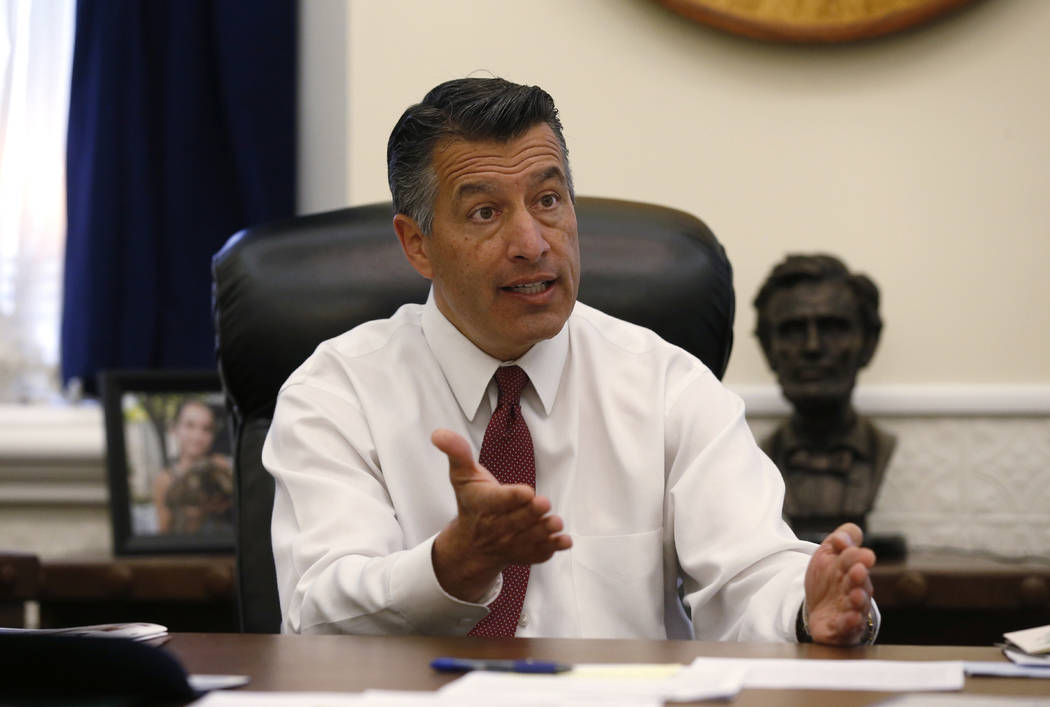

CARSON CITY — For outgoing Gov. Brian Sandoval, the journey to the Governor’s Mansion started with a gamble — and a lingering regret.

It was 2009. The country was in the throes of the Great Recession, and few states were hit as hard as Nevada, where tourism cratered and the housing industry collapsed.

Sandoval was a rising Republican star: a former attorney general mentored by Republican giants Paul Laxalt and Kenny Guinn. He was then the youngest judge on the federal bench in Nevada — a potential lifetime job. So when Sandoval announced he was leaving that job in August 2009 to challenge the sitting governor from his own party, some people thought he was out of his mind.

But Sandoval, whose family moved from California to Fallon when he was in second grade, and who later grew up in Sparks, was convinced he had the right ideas to move the state forward.

“Here was an opportunity to serve my state. And I didn’t want to have that regret for the rest of my life driving down to the courthouse thinking I could have made a difference,” Sandoval said in an interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal as he prepares to leave office Jan. 6 as one of the more popular elected officials in Nevada.

That leap was rooted in a decision he’d made two decades earlier.

Growing up, Sandoval had always planned on joining the military. As a young clerk at a law firm soon after graduating from Ohio State University’s law school, he scheduled a physical and an interview with the Navy and planned on going into the JAG program.

The day before he was set to leave for that interview, a fellow clerk told a partner in the firm of Sandoval’s plan.

“That day they came down and made me an amazing offer to make me an associate attorney,” Sandoval said.

Uncertain about his future and facing hefty student debt, he jumped at the $36,000-a-year offer. He thought he’d “died and gone to heaven.”

Sandoval canceled the Navy interview. That decision follows him to this day.

“One of my biggest regrets in life was not joining the military. There aren’t many days, particularly in my interactions with the military, that I don’t have a regret for not doing that,” Sandoval said.

He would defeat Jim Gibbons in the 2010 primary, more than doubling the incumbent’s vote count, and easily fend off Democrat Rory Reid, son of former U.S. Sen. Harry Reid, in the general election.

What Sandoval inherited as governor proved more daunting than what he’d just accomplished. Nevada faced a $2 billion budget deficit. It had the nation’s highest unemployment and foreclosure rates, the second-highest uninsured rate and the lowest high school graduation rate. It had no money in its rainy day fund and owed the federal government $800 million for unemployment insurance benefits.

“It was really dark,” Sandoval said.

But eight years later, with achievements that include an overhaul of Northern Nevada’s economy by attracting the likes of Tesla, Apple and Google; landmark education initiatives and funding; and being the first Republican governor to accept Medicaid expansion, which granted access to health insurance for more than 200,000 Nevadans, the 55-year-old Sandoval is confident he’s accomplished everything he set out to do.

The state’s unemployment rate has dropped below 5 percent; its uninsured rate is under 9 percent. Graduation rates for the state and Clark County hit all-time highs this year, and not only has that $800 million debt been paid off, but the unemployment insurance fund now has $1.5 billion, according to Sandoval’s office.

“I’m just grateful that I had the privilege of serving as the governor of this state,” Sandoval said. “I’m grateful that I had a team, with (chief of staff Mike Willden) and everyone on my staff, my Cabinet that were so committed to doing whatever it takes to put the state back, to put it on a trajectory that will put us in a position to be economically successful for years to come.”

Staying optimistic

Sandoval had lofty goals, but his governorship got off to what can only be characterized as a rough start.

Sitting in the Capitol building the night before he was to give his inaugural speech, Sandoval and childhood friend Dale Erquiaga were putting the final touches on his 2011 inaugural speech.

That night in Carson City was bitterly cold — maybe Mother Nature’s sign of what was to come for the new administration. So cold that space heaters were being used throughout the nearly 150-year-old building.

“Running a bunch of space heaters in an antique building late at night when it’s super cold is not a good thing to do,” Erquiaga recalled in October during an unveiling for Sandoval’s official portrait.

The fuse box blew, and the power to the Capitol was gone.

“So one of the first official acts of the Sandoval administration, not yet sworn in, was to wake up a bunch of state employees and tell them they had to come fix the fuse box at the state Capitol,” Erquiaga said.

Call it foreshadowing. Not only for the next day, when the public address system failed in the 11-degree weather, but also for the first months of Sandoval’s tenure.

But Sandoval was optimistic about what he could get done, and that showed in his 10-minute speech, when he used “optimism” in some form 10 times.

“The Nevada I know will choose action, courage and opportunity. We will choose optimism. I know this in my heart,” he told the crowd.

But converting optimism into success was easier said than done, as he’d come to find out.

Sandoval remembers being met by a chorus of boos from state workers when he walked into the Nevada Department of Transportation office that year.

On the campaign trail, Sandoval had promised to stabilize state spending while not raising taxes to combat the $2 billion deficit. State employees got 6 percent pay cuts, were forced to take 12 furlough days per year and lost their longevity pay and step increases.

Those workers were angry and let the new governor know it.

“We were trying to minimize those types of impacts,” recalled Sandoval’s former chief of staff and longtime friend Heidi Gansert. “Because they impact families. All decisions around cuts are difficult because he feels it at a personal level.”

In his first budget, he tried to pull funding from a local government entity and put it toward state spending, ruffling the feathers of Democrats in charge of the Legislature.

Then the Nevada Supreme Court weighed in, ruling the budget maneuver unconstitutional.

“Then the real Brian Sandoval emerged,” said Eric Herzik, a University of Nevada, Reno political science professor.

What emerged in the final weeks of that 2011 legislative session was the governor who would quickly earn a reputation as one who, like his friend and mentor Guinn, could buck partisan politics to work with both sides.

“We haven’t always agreed, but we have been able to work together to find a happy medium,” said state Sen. Mo Denis, D-Las Vegas, who led the Senate majority in 2013.

Case in point:

One of Sandoval’s priorities for 2011 was to lay the foundation for a long-term economic development plan, which started with taking that power from the lieutenant governor’s office and putting it under the purview of the governor.

He had broached the idea in his State of the State address and garnered support for the plan from Democratic Legislative leaders Assembly Speaker John Oceguera and Senate Majority Leader Steven Horsford.

“That was one of those moments that really changed the history of this state,” Sandoval said.

Creating a legacy

Over the next seven years, Sandoval would rack up the achievements.

That economic development bill from 2011 led to the creation of the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, which would prove vital in attracting major tech players such as Tesla, Apple and Google to the Silver State and effectively revamping the economy of Northern Nevada, as well as bringing the Raiders to Las Vegas.

Sandoval became the first Republican in the country to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act, which led to 200,000 more Nevadans being covered by health insurance.

He was a champion of Nevada’s outdoor spaces, spearheading discussions and efforts with the federal government to protect sage grouse habitat and significantly expanding and modernizing the state park system.

But nothing was as impressive as what Sandoval did in 2015, Herzik said.

Working with a Republican-controlled Senate and Assembly, Sandoval passed the largest tax increase in state history — a $1.5 billion tax package that would largely fund Sandoval’s education initiatives such as all-day kindergarten and Zoom Schools.

Sandoval knew there could be political fallout from the tax hike. But he also knew that to continue to attract big tech companies, education in the state needed to improve.

“I didn’t wake up saying I want to raise taxes in Nevada. But I did wake up saying I want to improve education,” Sandoval said. “This state would never be where it needs to be unless we invested in education. And the only way we could do that is imposing a new tax.”

Herzik called getting that tax passed “one of the most amazing moves by an executive I’ve ever seen.”

Sandoval proved to be a stark contrast to his predecessor.

“With the previous administration, it was very difficult. Gibbons didn’t really come over to the Legislature a whole lot,” said Denis, who has served in the Legislature since 2004.

But with Sandoval, who served in the Assembly in the 1990s, that changed. He made a point to speak with every lawmaker, Republican and Democrat, caucus leader and freshman, to discuss their priorities.

“He brought everyone into the office one by one. He showed genuine interest in what my priorities were and what I wanted to accomplish,” said former Assemblyman Paul Anderson. “That always stuck with me.”

And throughout most of his term, Sandoval accomplished his goals by developing a trust with lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

“When you made a handshake, a deal was a deal,” Oceguera said.

Sandoval’s seeming lack of concern for the partisan game extended beyond his interactions with the Legislature.

has shown little hesitation in appointing those from both sides to judicial seats, commissions, boards and even his own Cabinet, often siding with experience and ability over any form of partisan loyalty.

Two notable appointments were the selections of Lidia Stiglich to the Nevada Supreme Court and Becky Harris to chair the Nevada Gaming Control Board. Stiglich, a Democrat, became the first openly gay justice to serve on the state’s high court. Harris became the first woman to lead the Control Board.

Looking forward

Sandoval hopes that after he leaves, people won’t remember his eight years as governor for a single achievement, but rather for everything he feels that he has accomplished in his two terms.

“I didn’t set out to have any legacies. But what I set out to do was to position Nevada to be in a place where we’re the forefront of the new economy,” he said.

But even for a successful politician — Sandoval no longer gets booed when he visits the NDOT offices — life in the public eye takes its toll.

With his split from his ex-wife Kathleen at the beginning of 2018, Sandoval became the state’s second consecutive governor to divorce in office. And with his marriage to gaming executive Lauralyn McCarthy in August, he became Nevada’s first sitting governor to marry.

As Sandoval prepares to hand off the office to incoming Gov.-elect Steve Sisolak, the state faces new issues.

Affordable housing and doctor shortages will be at the forefront of Sisolak’s tenure, in part because of the economic and population growth the state has experienced in the last eight years.

One of the biggest criticisms of Sandoval, Herzik said, “is that his priorities worked too well.”

Sisolak said he is looking forward to building upon the progress made under Sandoval.

“I have been lucky enough to count Governor Sandoval as a friend long before I got into the race to succeed him. He has not only been an asset to me during my time on the (Clark County) Commission and as I make this transition, he has been a great leader for Nevada as well,” Sisolak said. “It’s an honor to follow a governor who always strove to put the interests of Nevadans ahead of political pressures.”

As for Sandoval, he is still figuring out what his next priorities will be.

He’s not considering any sort of run for another office at this point, and the only thing he is committed to now is teaching a new “Law and Leadership” program at UNLV’s Boyd School of Law, modeled after a program of the same name from his alma mater, Ohio State.

Beyond that, Sandoval’s still weighing his options for his future, with his children, James, Maddy and Marisa, in mind.

“I’m very excited about that,” Sandoval said of the teaching position. “But I still have two kids in college and one in high school. So I’ve got to make a living. I’m going to sort out some opportunities.”

Contact Capital Bureau Chief Colton Lochhead at clochhead@reviewjournal.com or 775-461-3820. Follow @ColtonLochhead on Twitter.

Timeline

Key events in the political career of outgoing Nevada Gov. Brian Sandoval:

1994-1998 — Served two terms in Nevada Assembly.

1998 — Appointed to Nevada Gaming Commission by Gov. Bob Miller.

2002 — Elected Nevada attorney general.

2005 — Appointed by President George W. Bush to the United States District Court of Nevada.

August 2009 — Resigned from the federal bench to run for governor.

November 2010 — Elected governor of Nevada.

June 17, 2011 — Legislature passes bill giving governor’s office control of economic development in the state and creation of the Governor’s Office of Economic Development.

Dec. 12, 2012 — Sandoval announces that Nevada would opt-in to Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act

Sept. 11, 2014 — Legislature passes and Sandoval signs bill approving $1.25 billion in tax breaks for Tesla to build the company’s flagship Gigafactory 1 in Northern Nevada.

Nov. 4, 2014 — Sandoval elected to a second term as governor.

June 10, 2015 — Sandoval signs bill approving his $1.5 billion tax package, include the Commerce Tax, to fund his education initiatives.

Oct. 17, 2016 — Sandoval signs bill approving $750 million public subsidy to help fund construction of a new football stadium as part of an agreement to move the Oakland Raiders to Las Vegas, which will become the state’s first NFL team.