Joe Neal dies, first Black state senator in Nevada

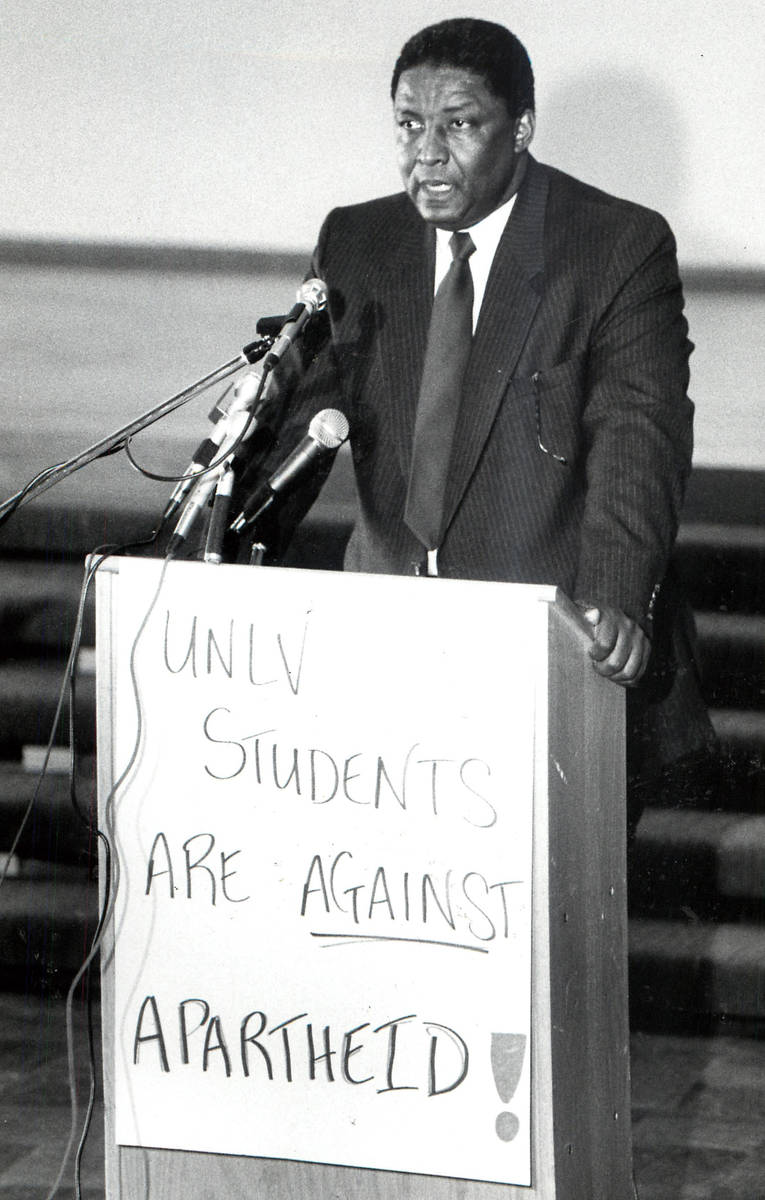

Joe Neal, Nevada’s first Black state senator who served more than three decades in the legislative chamber and championed the poor and working-class, has died.

Neal, who served 32 years in the state Senate, was 85. He died on Thursday while under medical care.

“My Dad, after a long-fought battle, succumbed to an illness,” stated his daughter, Sen. Dina Neal, D-North Las Vegas.

“He passed away at 10:25 p.m. Dec. 31 at Dignity Health, Siena Campus, in Henderson, where he received the best care, surrounded by family,” she added.

‘Giant of a man’

Neal was the first Black person to become a major-party nominee for governor in the state, losing to Republican Gov. Kenny Guinn in the 2002 general election. He also made an unsuccessful run for governor in 1998.

Politicians and community leaders on Friday expressed sorrow over Neal’s death.

“I was deeply upset and saddened to hear of the death of Joe Neal, the second-longest serving State Senator in Nevada history, a champion for the African-American community, a warrior for social justice, and a tireless advocate for Nevada’s workers,” Gov. Steve Sisolak said. “True to his nature, Joe fought until the very end, battling illness for a long time.”

Former Nevada Assemblyman Wendell Williams said Neal was a pioneer in the state. One of Neal’s greatest accomplishments, Williams said, was leading the way in securing public safety improvements in commercial buildings in Nevada following the deadly MGM Grand fire in 1980.

“He was the first senator from our neighborhood, our community,” Williams said. “I grew up probably about 10 miles from where he grew up. They used to give African Americans a test to be able to vote. He was the first person who passed that test, by the way.”

Sen. Mo Denis, currently the Senate president pro tem, described Neal as a legend.

“When I think of Joe Neal, he was both a giant of a man, both physically and also in the community for the things he did,” Denis said, adding “he was able to accomplish a lot, but more importantly, he was very passionate about representing his community. He was very respected as a legislator and, as a person, he really made our community much better.”

A press release from his former campaign manager, Andrew Barbano, described Neal as “the best who ever was.”

‘Champion for the little guy’

Neal earned the nicknames “Westside Slugger” and “Conscience of the Legislature.” He was known for his oratorical talents, his tactical ability and his zeal for working on behalf of the poor and marginalized.

“He was always a champion for the little guy,” U.S. Rep. Dina Titus, a Democrat who served alongside Neal in the state Senate for 13 years, told the Review-Journal in 2019. “He was willing to fight against any odds for what he believed was right.”

On Friday, Titus recalled their friendship and noted how they met up every few months after Neal retired.

“I would ask his advice, but I would also listen to his stories of Nevada history and some of the things he’d been through and his perception of how things have happened in the state,” Titus said. “He saw a lot of changes over the time he was here and making a difference.”

Early years

Joseph M. Neal Jr. was born July 28, 1935, in Mound, Louisiana, and moved to the Las Vegas Valley in 1954 after graduating from high school.

Neal recalled for a UNLV University Libraries oral history that he moved into a rental home he shared with his mother and other boarders on D Street in the then-segregated Westside neighborhood.

In 1954, Neal joined the Air Force so that he could earn GI Bill benefits and pay for a college education he otherwise could not afford. He served in the U.S. Air Force from 1954 to 1958 and enrolled at Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1961 to study political science.

Neal earned a bachelor’s degree in political science and history from Southern University, did postgraduate study in law and studied civil identification and criminal investigation at the Institute of Applied Science in Chicago.

While an undergraduate, Neal joined other students in civil rights demonstrations.

“Blacks did not have any rights that whites would respect at that time, so you had to force that upon them and make sure we were not invisible,” Neal told the Review-Journal in February 2019. “Back then, they would send you into service to fight, and they would not give you the right to vote.”

After returning to Las Vegas, Neal worked as an equal opportunity compliance officer for Reynolds Electrical & Engineering, charged with integrating the company — then one of Southern Nevada’s largest employers — into compliance with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. He also worked to fight discriminatory practices at North Las Vegas City Hall and area labor unions.

Stirring the pot

In 1972, after spending most of a decade working toward economic opportunity in the hotels and building trades — and especially at the Nevada Test Site — Neal, D-North Las Vegas, was elected to the state Senate.

Neal’s Senate win followed two failed attempts to run for the state Assembly and one failed run for the state Senate. In 2012, he told KNPR’s “State of Nevada” program that he ran partly to prove black people could.

“It was to get out there and stir the pot,” he said, “and let people know that people like myself … had an absolute right to get out there and run if they felt they wanted to be elected to something.

“I knew I had some issues and I wanted to create a situation where Blacks would be able to get elected to the state Legislature on their own terms.”

As a freshman senator, Neal memorized the Legislature’s rules of order — “I used to take that book and beat ’em up on it,” he said — and studied drafts of bills. He even viewed losing as a way to put his issues with a bill on the record.

“My whole makeup at getting elected to the Senate was not to go along to get along,” he told the Review-Journal in 2019. “People thought maybe I would sit in the background and just vote and stay along with the party structure, but I didn’t do that.”

Neal retired from the state Senate in 2004 after serving 16 regular legislative sessions and seven special sessions. His tenure included stints on the Interim Finance Committee and Legislative Commission. He also served as assistant majority floor leader (1985), assistant minority floor leader (1987), minority floor leader (1989), and president pro tem (1991).

Speaking up and speaking out

As Neal battled conservatives in his party, he also fought to land, and keep, committee chairmanships. He was known for his oratorical eloquence and his willingness to address unpopular topics, including the need to expand health care and the treatment of minorities by police.

In his UNLV oral history, Neal recalled challenging then-Gov. Mike O’Callaghan’s proposal in 1973 to issue the death penalty to anyone who killed a police officer.

“I’m sitting there as he gave his State of the State address, knowing, of course, that someone from the press will ask me about this particular statement,” Neal said. “So when they asked me about it, I said, ‘Why give the death penalty to one who kills policemen? Why not give the death penalty for killing a janitor? Life is life. It’s just as important to a janitor as it would be to a policeman.’”

Neal said his relationship with O’Callaghan was rocky after that.

“If (O’Callaghan) had something that I thought was correct and fair to the people of the state of Nevada and to the people that I represented, yes, I would support it,” Neal said in the oral history. “But if it wasn’t, I didn’t, and I would get up and talk against it. That was something that he didn’t like, if you could pick his legislation apart. He didn’t like that at all.”

Neal also tangled with gaming’s titans. His argued against a tax exemption Steve Wynn wanted for artwork that he had purchased. Neal called the exemption push “Show Me the Monet” and made it a centerpiece of his run for governor. Neal also argued against the spread of casinos into residential neighborhoods.

“See, gaming does not put anything back. It has a tendency to sweep the wealth in a community into a pyramid owned by a few folks. And that’s what it does,” Neal said in the oral history. “So if you have a gaming house in your community, then that gaming house is going to draw money from that community that should go for Medicare or groceries or paying the rent and things of that sort. It has a tremendous social impact upon the residential areas. So that was one of the reasons that I supported a moratorium on gaming.”

Neal helped state senators in 1977 pass the Equal Rights Amendment out of that half of the Legislature, but it failed in the Assembly. His unrelenting effort helped tighten Nevada’s commercial fire safety codes after the tragic MGM Grand fire in November 1980 in which 85 people died.

With Titus, an eventual congresswoman, Neal issued warnings about the danger of deregulating Nevada’s electricity market amid Enron Corp.’s chicanery. He also fought against special interest legislation.

He won several awards for his political service, including the Rev. Jesse Jackson Distinguished Political Award from the NAACP and a Lifetime Commitment Award, Nevada AFL-CIO.

Barbano said Neal lost his wife, Estelle Deconge Neal, to breast cancer in 1997 after 32 years of marriage. He was the father of five: Charisse, Tania, Withania, Dina and Joseph; grandfather of 10 and great-grandfather of two.

Contact John Przybys at jprzybys@reviewjournal.com. Follow @JJPrzybys on Twitter. Contact Glenn Puit at gpuit@reviewjournal.com. Follow @GlennatRJ on Twitter. Former Review-Journal assistant city editor Matthew Crowley contributed to this report.