County, city try new ways to help homeless after COVID-19 complex closes

Clark County and the city of Las Vegas spent more than $32,600 per patient to isolate and quarantine the homeless for 11 weeks in a temporary facility at Cashman Field.

The so-called ISO-Q Complex closed June 30, after the governments spent approximately $8 million to build and staff the facility intended to stop the spread of COVID-19 among the homeless.

Instead, Clark County is continuing with a less costly plan to deal with cases of the disease caused by the new coronavirus among the particularly vulnerable population.

At the same time, it’s not clear whether the new approach will be sufficient if Clark County’s recent spike in COVID-19 cases continues.

The ISO-Q Complex, which opened April 13, was erected in two weeks and was designed to accommodate 500 people. During its roughly 2 1/2 months of operation, it served 245 and administered 860 COVID-19 tests, 17 of which were positive, and helped 22 patients recover.

Kathi Thomas-Gibson, the city’s director of community services, acknowledged the operation was costly but said it was a prudent safeguard since officials had no idea at the time whether the pandemic would overwhelm local hospitals.

“What price tag are we putting on a human life?” she asked, adding that the city had to prepare for the worst because it would not have been able to expand capacity after the fact.

Planned for a ‘worst-case scenario’

“The expenditures were necessary because we needed to be proactive. We planned for a worst-case scenario and we did not have that, and so that’s a blessing,” she said.

The city is continuing its “hired, housed and healthy” approach to homelessness at their Courtyard Homeless Resource Center, Thomas-Gibson said.

The department is setting aside federal dollars for housing assistance and other programs for the homeless and those at risk of becoming homeless due to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

City and county officials designed the ISO-Q to relieve hospitals of homeless patients who were not seriously ill but had nowhere to quarantine.

On its busiest days, the complex housed 66 people on April 30, and 54 on May 17 and May 18.

Since then, the numbers declined, city officials say.

Clark County in April also funded 161 isolation and quarantine beds at existing facilities valleywide for a fraction of the cost.

To fund the beds at Well Care Living for 90 days, it costs the county about $1.2 million.

The county now has a similar arrangement in place with CrossRoads of Southern Nevada, a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility, paying on a per patient, per day basis. The Southern Nevada Health District approves each client and determines the length of stays.

Dr. Cortland Lohff, acting chief medical officer for the health district, said that despite the closure of the ISO-Q facility, the district is continuing to partner with agencies to increase testing and outreach among the homeless.

“Although we’ve seen cases among homeless folks, we’ve certainly not seen a large number of cases or outbreaks (like) other big cities, and in some ways we’ve been lucky in that respect,” Lohff said.

“One of the most important priorities is to continue to investigate folks who are positive for COVID-19 and make sure they’re getting the care they need and they’re appropriately isolated … and to identify their contacts and test their contacts and make sure they are also placed in quarantine.”

Fire Department’s backup plan

While the current surge in COVID-19 cases has Southern Nevada hospitals nearing capacity, the Clark County Fire Department has plans ready to create a medical surge center at the Las Vegas Convention Center should the need arise.

But before that would happen, each hospital would have to reach its surge capacity.

“Before the Convention Center would ever get activated, all those hospital surge plans would have to come first, and they’re monitoring the numbers,” county spokeswoman Stacey Welling said.

Such a scenario isn’t likely, according to University Medical Center CEO Mason VanHouweling. He said the public hospital has not seen a spike in COVID-19 cases among the homeless since the closure and that the ISO-Q had run its course.

“They only had a few patients a day there, and it just didn’t warrant running such a large operation when we have capacity in our hospitals in Southern Nevada,” he said.

“Every hospital is going to do their part taking care of the homeless population.”

The health district also has had a plan for a similar facility in the works since March 30, when the board voted to build a $3 million, 40-bed isolation facility that at the time was “expected to be completed in no more than 10 days.”

Lohff said details on that facility are still being worked out but noted it would instead be a 20-bed facility and cater to patients that test positive but don’t have a safe place to quarantine.

In the meantime, there are open beds at facilities such as CrossRoads.

The treatment center, which was previously losing $300,000 a month under different management, had transformed itself, largely because of public contracts with Clark County to help the homeless with substance abuse and case management and from minimizing exorbitant prices charged by some vendors.

‘Smart and creative approach’

On June 25, CrossRoads CEO Dave Marlon had an empty unit for coronavirus patients.

He then received a call from the health district saying that two patients — inmates who tested positive at a halfway house — would be on their way to isolate.

The unit, which first started operating in April, opened back up the next day and over the next 12 days admitted 10 COVID-19 patients, he said.

“They’re expecting a second spike,” he said. “And we’re like a little shelter detox. We’re always around to be able to be here as a community partner.”

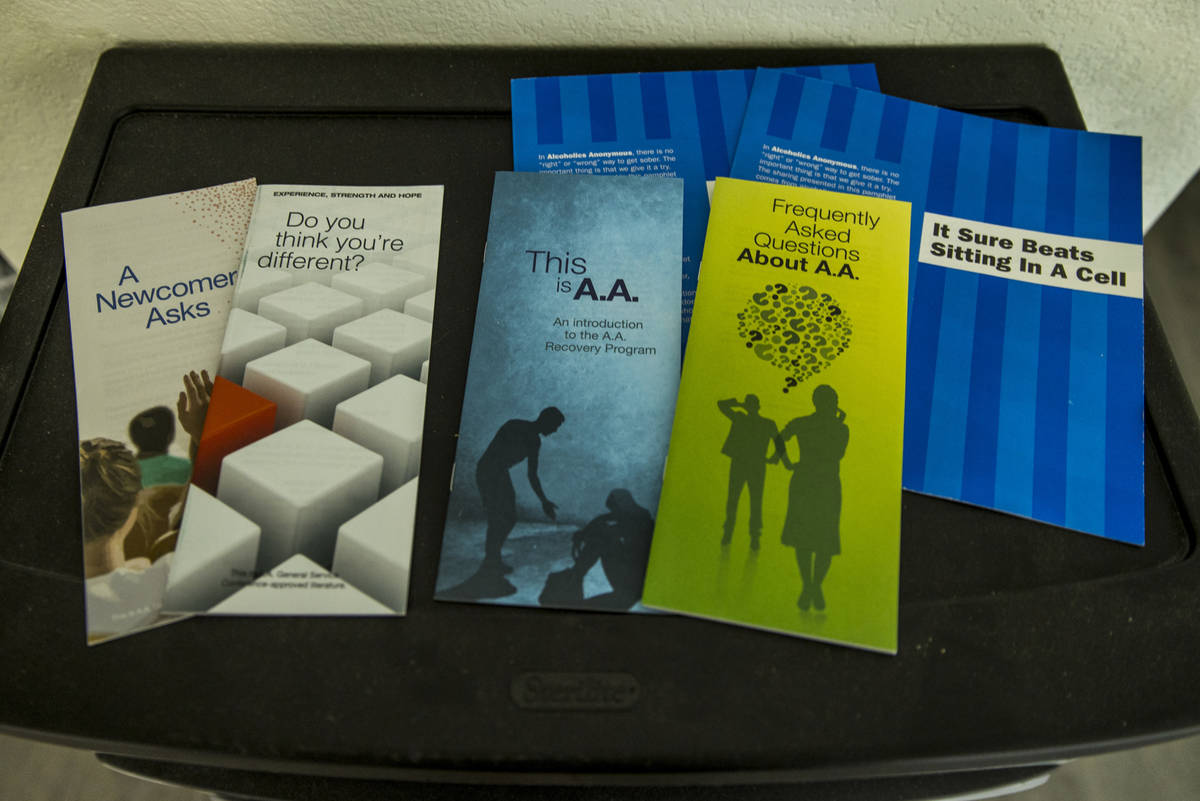

The facility provides 24/7 nursing, counseling, access to doctors, case management and dietitian-approved meals.

As of Wednesday, there were three patients in the unit and 33 beds available. A total of 16 have been housed since the county signed the contract in April.

Marlon called the arrangement with the county a “smart and creative approach.”

“The ISO-Q spent a ton of money and with this county contract, there’s been very little spent to be able to accomplish this same thing,” he said.

Dealing with the sick patients also gives the facility an opportunity to address the barriers contributing to their homelessness.

One patient’s story

One of their patients, 42-year-old Raggie Cole, decided to use the opportunity to stay at CrossRoads and get sober.

“It was a blessing, being supported by strangers,” he said. “I probably would have been one of those numbers that was classified as dead.”

Cole’s mother died from stage 4 liver cancer March 24, and his aunt died from coronavirus shortly afterward.

Cole had been his mom’s full-time caretaker, battling an alcohol addiction during the pandemic and sporadic unemployment. After she died, he was forced to move out of his mom’s senior living development and found himself homeless.

In early April, he first felt a shortness of breath. He had asthma so he went to Valley Hospital Medical Center to get a prescription for an inhaler. Instead, he tested positive for COVID-19 and was put on a ventilator.

“It felt like somebody just poured cement on my chest,” Cole said.

While in the isolation unit at CrossRoads, Cole looked through the window and saw clients walking through, receiving treatment, and became curious about living a sober life.

It was a promise he had made to his mom, “to get right, stop drinking.”

“The death of my mother changed my life. I don’t want to break my word,” he said, holding a heart-shaped locket containing her ashes.

Cole checked out of the facility July 4 to live with family out of state, but he told the Review-Journal he plans to continue his sobriety and “take it one day at a time.”

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @ByBrianaE on Twitter. Review-Journal staff writer Mary Hynes contributed to this report.