Changing faces: Trump’s presidency sees high staff turnover

WASHINGTON — Kathryn Dunn Tenpas had carved out an important but unsexy academic specialty for herself when she began to study hiring practices, with a focus on turnover rates, in White Houses from President Ronald Reagan onward.

“It was a sleepy little subfield,” she recalled from her home in Maryland.

Then came President Donald Trump, whose surprise victory in 2016 turned the Brookings Institution nonresident senior fellow into a go-to source for reporters looking to put Trump’s record-breaking staff turnover in context.

The 45th president, who became famous for telling reality-show participants, “You’re fired,” on “The Apprentice,” has lorded over record churn among top aides and Cabinet members.

In his only term, Trump has burned through four chiefs of staff — Reince Priebus, John Kelly, Mick Mulvaney and Mark Meadows — as well as four national security advisers and four press secretaries. The comings and goings have been so prolific that Tenpas developed a name for the phenomenon: “serial turnover.”

The jobs with the highest turnover were deputy national security adviser and director of communications. Six individuals served in each slot.

If Trump names someone to replace communications director Alyssa Farah, who left the White House in early December, there will have been seven people in that job.

“No matter how you slice the data, the turn-out is off the charts,” Tenpas said.

Losing the A-team

By the end of Trump’s freshman year in office, 35 percent of his A-team were no longer on the job. That’s more than double Reagan’s first-year turnover, which had been the highest before Trump.

“Just 32 months into the Trump administration, the rate of turnover had exceeded his five predecessors’ full first terms,” Tenpas wrote on the Brookings blog.

The White House cited Trump’s style as a reason for the figures.

“The high turnover is due to the president’s work ethic and how hard he works. And he’s relentless, and it’s hard for his staff to keep up with him,” assistant press secretary Karoline Leavitt told the Review-Journal. “I’m 23 years old, and it’s hard for me to keep up with him.”

Trump not only fired or forced a record number of Cabinet members and top staffers to resign — Tenpas came up with a new term, RUP, for “resigned under pressure” — but also has often announced his decision with “the added dimension of public humiliation on Twitter.”

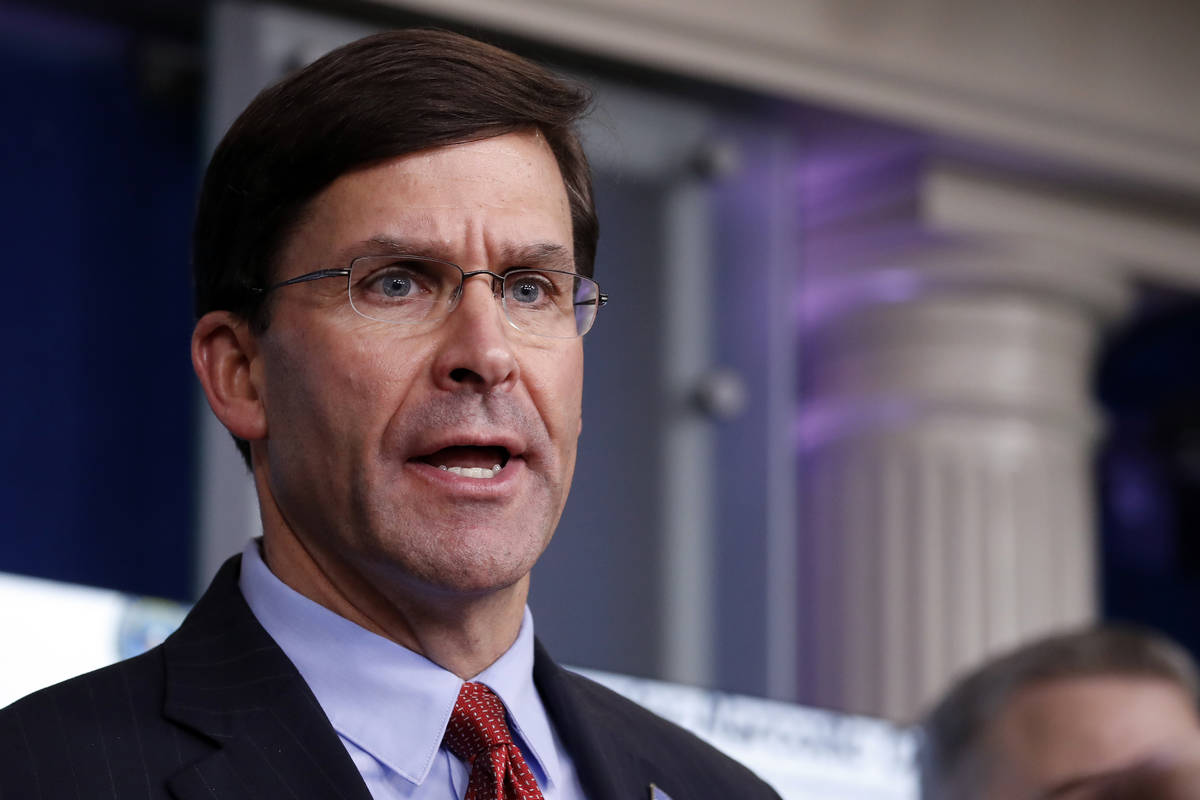

On Nov. 9, when Trump fired Defense Secretary Mark Esper, he wrote on Twitter, “Mark Esper has been terminated. I would like to thank him for his service.” Then Trump named an acting replacement.

Before the month was over, Trump also fired Chris Krebs, director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, on Twitter. Krebs had released a statement that contradicted Trump’s assertions of election fraud by calling the Nov. 3 election “the most secure in American history.”

Tenpas also examined Trump White House staffers who were “survivors,” and put them under three headings. “Trusted confidants” include daughter Ivanka Trump and her husband Jared Kushner, who worked as unpaid aides, and uber-loyalists such as Stephen Miller, Dan Scavino and the since-departed Kellyanne Conway who had relations with Trump before his 2016 victory.

The second group, economic and trade policy wonks, consists of U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, trade policy handler Peter Navarro and Richard Burkhauser, who serves on the Council of Economic Advisers.

The third group, “outside the public eye,” was now down to one person, Lisa Curtis, a member of the National Security Council and senior director for South and Central Asia, before she left on Friday.

Some survivors

Tenpas has a theory about Cabinet members such as Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson and Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who were Trump’s first picks and lasted on the job until this week when DeVos resigned.

“I think there were a lot of issues that Trump didn’t care about,” Tenpas said, and those individuals were more likely to endure. “If you were a Cabinet secretary on an issue that he cared about, then it was harder to survive.”

A key policy area for Trump is immigration, and he has burned through a number of Department of Homeland Security chiefs. He promoted his first secretary, John Kelly, to chief of staff. After Kelly’s successor, Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, resigned under pressure in April 2019, Trump named two acting secretaries, Kevin McAleenan and Chad Wolf, neither of whom was confirmed.

The administration’s musical chairs in Homeland Security led to the use of “legal gymnastics” necessary to appoint replacements in keeping with department rules. Those maneuvers put leadership in legal jeopardy and created vacancies in department ranks. As the Partnership for Public Service reported in August, only 35 percent of Senate-confirmed positions had permanent leaders with the Department of Homeland Security.

Learning curve, burnout

Before Trump, her study informed Tenpas about the rhythm of new administration hires. Officials often would tell her that it took them half a year to master the job, and after another six to nine months, many were burned out. Generally, a new administration’s staff starts to leave after two years.

The first batch of a president’s hires, Tenpas noted, tends to include individuals who have a history with a new president.

“The second string comes along midway through the first term,” Tenpas said, and they don’t have the same stuff.

With Trump, turnover was on steroids, and new elements to the old churn developed. Tenpas never before saw staffers who left a White House in less-than-ideal circumstances later return to the same administration. But then Communications Director Hope Hicks, who resigned in 2018 after she admitted to a House committee that on occasion she told “white lies,” returned to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. in February.

Johnny McEntee, who like Hicks worked for the Trump organization before Trump ran for president, left the White House under a cloud when then-chief of staff Kelly learned that the onetime bodyman had a gambling problem. In February, McEntee returned as director of the Presidential Personnel Office, whence he has been involved in the purge of staffers seen as insufficiently loyal.

On Dec. 1, Trump’s second attorney general, William Barr, told the Associated Press that “to date, we have not seen fraud on a scale that could have effected a different outcome in the election.”

As Trump continued to blame voter fraud for his election loss, he turned his ire on Barr on Twitter, causing some to wonder whether the president would dispense with Barr with the same hostility he had exhibited when he fired his first attorney general, Jeff Sessions.

On Dec. 14, Barr put an end to the speculation when he presented Trump with a letter of resignation.

This time, Trump posted a fond farewell on Twitter.

“Just had a very nice meeting with Attorney General Bill Barr at the White House. Our relationship has been a very good one, he has done an outstanding job!” the president announced. “As per letter, Bill will be leaving just before Christmas to spend the holidays with his family.”

Tenpas, now also a senior fellow at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center, tweeted that the outgoing president had burned through two Cabinet secretaries in three departments, “another historic first. #instability.”

Contact Debra J. Saunders at dsaunders@reviewjournal.com or 202-662-7391. Follow @DebraJSaunders on Twitter.

An earlier version of this story reported that Lisa Curtis worked for the National Security Council. Curtis left on Jan. 8.