Paratrooper shares 1952 survival story of jumping through remnants of atomic bomb cloud

Relatively few paratroopers have jumped through the remnants of an atomic bomb’s mushroom cloud and lived to tell about it, especially 61 years later.

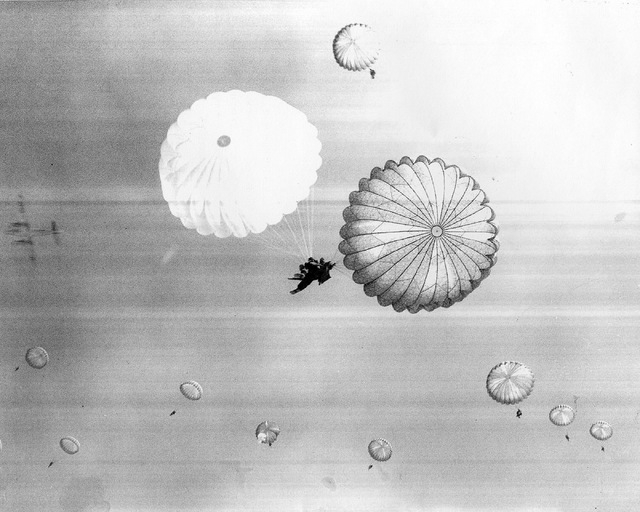

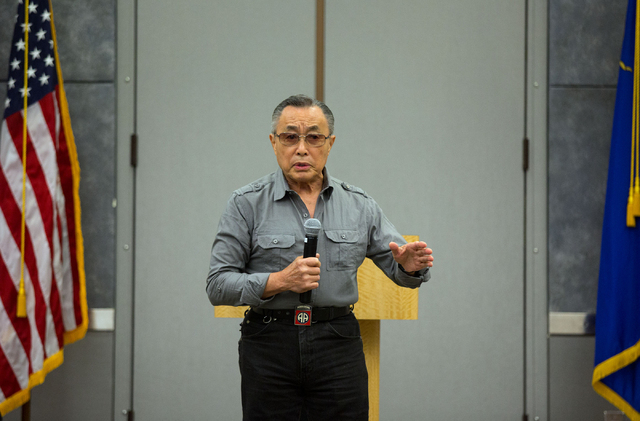

In fact, 82-year-old Al Tseu, who made such a jump over the Nevada Proving Grounds with 300 others from the 82nd Airborne Division, dodged two bullets that day in 1952: he somehow avoided inhaling deadly radioactive particles and also managed to deploy his reserve parachute seconds after his main chute malfunctioned.

“I was the third man out of the airplane. I was counting, ‘one-thousand, two-thousand, three-thousand’ to open chute and nothing happened. Usually the parachute explodes with a ‘boom.’ I didn’t hear it that time,” he said Friday after speaking at the National Day of Remembrance event at the National Atomic Testing Museum.

He encountered what parachutists refer to as a “Mae West,” or the predicament caused by a line crossing over the top of the chute that divides the canopy into two parts. High in the sky it has the appearance of a bra worn by the buxom, mid-century movie star.

“I said to myself, ‘I don’t have the luxury of being panicked, or afraid,’ because I had no time left. I’ve got to work to get myself out of the situation,” the fit, older man from Honolulu said.

“I remember looking down on my rip cord. I pulled it. I consciously held the silk from coming out until less than about a second and a half. Then I threw it (the reserve chute) as far as I can up in the air and it caught the air and bloomed. There was no fear. There was no time for it. Panic was out of the question,” he said.

The occasion, for which Tseu was one of a half dozen invited speakers, was the fifth annual congressionally recognized day to mark the role of Cold War patriots in the nation’s nuclear weapons program.

The event is traditionally held at the National Atomic Testing Museum on East Flamingo Road where the Nevada Test Site takes center stage.

The test site, 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas, was first called the Nevada Proving Grounds from 1951 to 1954 where above-ground nuclear weapons tests were conducted. It has been officially known as the Nevada National Security Site since its well-known name, the Nevada Test Site, was changed by the Department of Energy in 2010.

Tseu recalled how hundreds of soldiers and Marines were hunkered down in trenches near Camp Desert Rock, three miles from ground zero, when the 31-kiloton bomb, Charlie, was air-dropped over the proving ground as part of Operation Tumbler-Snapper on April 22, 1952.

When it detonated, it unleashed twice the explosive yield of the bomb the United States dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, in 1945.

“All of a sudden I could feel the heat that came over us. And it was hot,” he said. “As I looked up, I could see a rolling, fiery doughnut. It was huge. I’ve never seen anything like that.”

About a half hour after the explosion, two companies of paratroopers from the division’s 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment boarded trucks that took them to 20 C-47 cargo planes at the Indian Springs airfield.

By the time he exited the plane the mushroom cloud had dissipated but fallout lingered closer to the ground.

After his aircraft entered the drop zone and he had made the jump with the tangled main chute and reserve chute open, he looked down and saw a photographer.

“When I landed, he was right next to me. I said, ‘What the heck are you doing here?’ He said, ‘Never mind, soldier.’”

Then, Tseu, wearing his battle gear, ran through the ground-zero experimental pens where sheep and goats and other animals had been exposed to the blast and radiation.

“I could see they were burned. Some were so red, really red from the radiation,” he recalled. “I noticed there were no Joshua trees around. There was one (sheep) I’ll never forget. His eyes were wide open, red and bloodshot. It looked at me but I don’t think it saw anything. And so we double-timed out of there.”

He ran with other soldiers until they were met by scientists with Geiger counters who took radiation measurements of their uniforms and gear. He was a corporal at the time on a three-year enlistment.

Tseu said “10 or 15 years later” he received a questionnaire from an atomic veterans association. He was married and had a family. The association wanted to know about his health and his children.

So, in a comment box he wrote, “‘I’m as healthy as can be. I’ve got four children and they’re healthy. But I notice when I check them at night to see if they’re OK, They glow green.’ It was just a joke.”

Later, though, he learned through letters that some of his friends in his parachute company had become sick with cancer.

“I remember one very clearly, a good buddy of mine. He wrote to me. He said, ‘Al, how are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’m fine.’”

His friend wrote back, saying, “Well I have thyroid cancer and I think it could be related to the A-bomb test.”

Tseu never heard from him again.

“So far I’m OK and I’m just grateful,” he said.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.