Woman charges top US cardinal dismissed sex abuse case

HOUSTON — When Cardinal Daniel DiNardo first met Laura Pontikes in his wood-paneled conference room in December 2016, the leader of the U.S. Catholic Church’s response to its sex abuse scandal said all the right things.

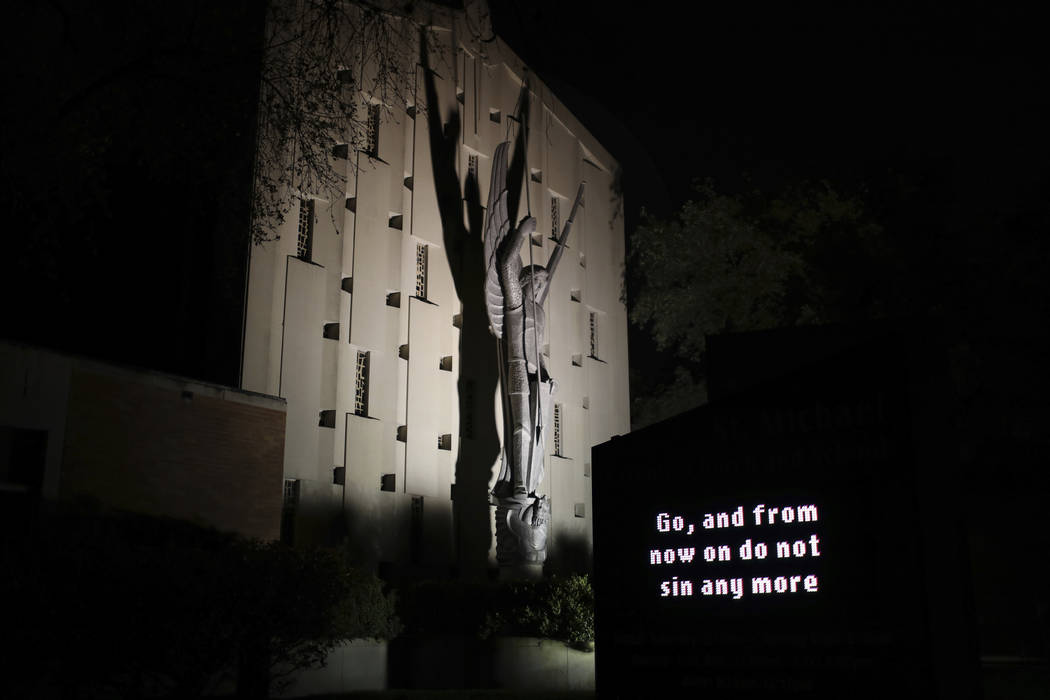

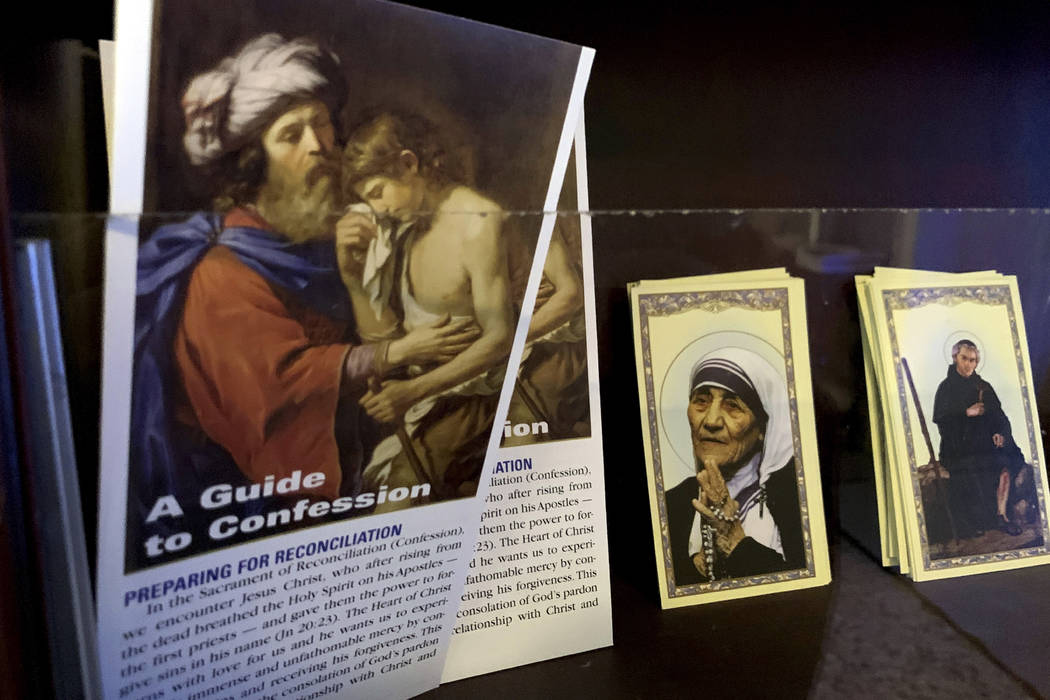

He praised her for coming forward to report that his deputy in the Galveston-Houston archdiocese had manipulated her into a sexual relationship and declared her a “victim” of the priest, Pontikes said. Emails and other documents obtained by The Associated Press show that the relationship had gone on for years — even as the priest heard her confessions, counseled her husband on their marriage and pressed the couple for hundreds of thousands of dollars in donations.

She says she was assured that priest, Monsignor Frank Rossi, would never be a pastor or counsel women again.

Months after that meeting, though, she found out DiNardo had allowed Rossi to take a new job as pastor of a parish two hours away in east Texas. When her husband confronted DiNardo, he said, the cardinal warned that the archdiocese would respond aggressively to any legal challenge — and that the fallout would hurt their family and business.

On Tuesday, after written inquiries by the AP, the church followed through on promises to remove Rossi, announcing in a statement from his new bishop that he was being placed on temporary administrative leave.

Laura Pontikes, a 55-year-old construction executive in Texas, had been at a low point in her life when she sought spiritual counseling from Rossi, the longtime No. 2 official in the Galveston-Houston archdiocese DiNardo heads. Instead, she said, Rossi preyed on her emotional vulnerability to draw her into a physical relationship that he called blessed by God.

“He took a woman that went into a church truly looking for God, and he took me for himself,” she told the AP.

Criminal investigation

Rossi’s sexual relationship with Pontikes is now the subject of a previously undisclosed criminal investigation in Houston. Yet it is DiNardo’s handling of the case that poses far-reaching questions for the church in the #MeToo era, when powerful men and institutions are being called to account over sex abuse.

As the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, DiNardo will lead a meeting next week in Baltimore to address the church’s credibility crisis over its failure to fully reckon with sexual abuse, 17 years after it committed to cleaning house. DiNardo is expected to present his brother bishops with new proposals to hold one another accountable for sexual misconduct or negligence in handling abuse cases.

But Pontikes’ case lays bare that even leaders in the Catholic hierarchy who have vowed to do right by victims continue to fail them. Pontikes said DiNardo has been negligent by keeping in ministry a priest who “seduced, betrayed and ultimately sexually victimized” her, Pontikes’ therapist told Texas prosecutors.

Baltimore meeting

The June 11-14 meeting in Baltimore is part of the church’s effort to confront sexual abuse worldwide. In a little more than a year, Pope Francis admitted he made “grave errors” in Chile’s worst case of cover-up, an Australian cardinal was convicted of abuse and a French cardinal was convicted of failing to report a pedophile.

In the U.S., a Pennsylvania grand jury blasted church leaders for following “a playbook for concealing the truth,” and attorneys general in at least 15 states are investigating sex abuse by Catholic clergy and its cover-up.

The Galveston-Houston archdiocese acknowledged an inappropriate physical relationship between Rossi and Pontikes, but asserted that it was consensual and didn’t include sexual intercourse. In a written statement to The Associated Press, it defended its handling of the case, saying Rossi was immediately placed on leave and went for counseling after Pontikes reported him.

Rossi returned to active ministry, without restrictions, based on recommendations from an out-of-state “renewal” program for clergy he completed, the statement said.

Pontikes filed a police report in August. Under Texas criminal law, a member of the clergy can be charged with sexual assault of an adult if the priest exploited an emotional dependency in a spiritual relationship.

Rossi’s attorney, Dan Cogdell, said Rossi is cooperating with the investigation and has met with police. He declined further comment.

Pontikes’ allegations against DiNardo add to questions about how he has dealt with abuse in the past. SNAP, a national group of survivors of clergy abuse, has called for him to resign as head of the bishops conference because he allowed predator priests to remain in ministry in Houston, as well as in his previous diocese in Sioux City, Iowa.

And when law enforcement raided DiNardo’s offices in November as part of an investigation into an alleged abuser, they found files locked away in a bank vault that the archdiocese had failed to turn over, according to police documents released last month.

Minimized issue in church bulletin

Rossi previously helped handle Galveston-Houston’s abuse cases for more than two decades. But in a church bulletin in February, he minimized the number of abusers nationwide, accused the media of hyping the scandal and insisted that while even one case of abuse was too many, the vast majority of accused were “good men” who simply made a “terrible single decision.”

Pontikes provided the AP with seven years of her email correspondence with Rossi, therapists, priests and friends, along with financial data and communications with the archdiocese. She told the Vatican in April that Rossi heard her confessions after their relationship became physical — a potentially serious crime under church law that DiNardo never asked her about. The Vatican said her complaint was under review.

The church, which has been grappling for decades with the sexual abuse of children, is now being forced to reckon with the idea that adults too can be sexually exploited by clergy. Last summer, amid revelations that ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick had preyed on adult seminarians, DiNardo used his pulpit to apologize for the leadership’s failures.

“This is especially true for adults being sexually harassed by those in positions of power,” DiNardo said Aug. 27. “We will do better.”

That statement gave Pontikes hope, but nothing changed, she said. She said she came forward to protect other women and expose DiNardo’s handling of her case, which has left her so distraught that she can barely sleep or work.

“They’re not going to play with my life like this,” said Pontikes. “They just can’t get away with it … Somebody had better stand up and tell the damned truth.”