Turkish PM vows new gesture aimed to cool protests

ANKARA, Turkey — Turkish activists leading a sit-in were considering a promise Friday by Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to let the courts — and a potential referendum — decide the fate of an Istanbul park redevelopment project that has sparked Turkey’s biggest protests in decades.

In last-ditch negotiations after Erdogan issued a “final warning” to protesters, his ruling party announced early Friday that the government would suspend a controversial construction plan for Istanbul’s Gezi Park until courts could rule on its legality. Even if the courts sided with the government, a city referendum would be held to determine the plan’s fate, officials said.

The unilateral pledge aimed to cajole protesters into ending a two-week standoff that has damaged Erdogan’s international reputation and led to repeated clashes with riot police. After initially inflaming tensions by dubbing the protesters “terrorists” and issuing defiant public remarks, Erdogan has moderated his stance in closed-door talks this week.

It remained far from clear, however, whether the overture would work. The park is one of the few green areas left in the sprawling metropolis of Istanbul and many protesters were still seething over the forceful operations by riot police that at times devolved into violent clashes with stone- and firebomb-throwing youths.

Such scenes prompted the European Parliament on Wednesday to condemn the heavy-handed response by Turkish police and sparked a heated riposte from Erdogan.

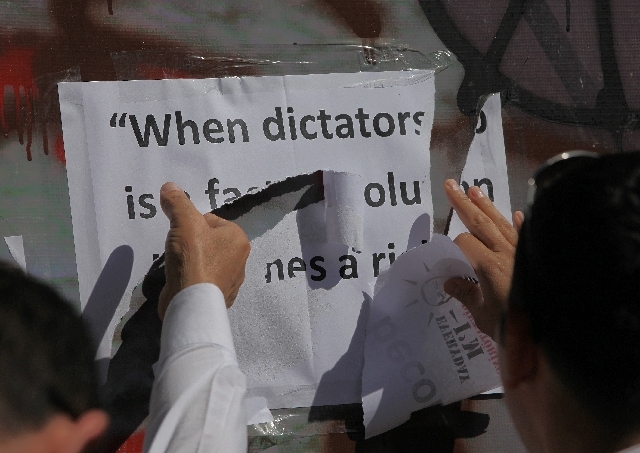

A May 31 police raid to clear out the park ignited demonstrations that morphed into broader protests against what many say is the prime minister’s increasingly authoritarian style of government. Five people – four demonstrators and a police officer -were killed in the protests that spread to dozens of other cities.

The protests have centered lately on three cities: Istanbul, Izmir on the Aegean Sea coast, and Ankara, the capital.

Erdogan’s opponents, including many protesters, have grown increasingly suspicious about what they call a gradual erosion of freedoms and secular Turkish values under his Islamic-rooted party’s government. It has passed new restrictions on alcohol and attempted but dropped a plan to limit women’s access to abortion.

Mobilizing instruments of democracy and the state – the courts, and a referendum – could shield the prime minister from accusations of an authoritarian response.

“Until the courts give their final verdicts, no action will be taken regarding Gezi Park,” said Huseyin Celik, a spokesman for Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party, after the meeting. “Even if the court … is in favor of our government’s decisions, our government will hold a referendum to see what our people think – what they want and don’t want.”

The Taksim Solidarity group, two of whose members were in the meeting with Erdogan, has emerged as the most high-profile from the occupation that began last month. But it does not speak for all of the hundreds camping in the park. Many say they have no affiliation to any group or party.

Tayfun Kahraman, one of the Taksim Solidarity members who attended the meeting, said he believed Erdogan had offered “positive words,” and that fellow activists would consider them in a “positive manner.” But he said those in Gezi Park would “make their own assessments.”

Suspicion within the park about Erdogan’s tactics and motives remains widespread, and the protesters are firmly entrenched:

In recent days, the festive tent-village atmosphere – with amenities like a medical station and library with donated books – has been marked by nightly piano concerts.

“The prime minister calls the people he pleases to the meetings and says some stuff,” said demonstrator Murat Tan. “We don’t care about them much. Today, we saved the trees here but our main goal is to save the people.”

Erdogan has pledged to end the protest, and has called his supporters to rally in Ankara and Istanbul this weekend. But those demonstrations could revive the discord between his conservative, Islamic base, and more liberal- and secular-minded progressives and others who are holed up in the park – potentially torpedoing his own efforts to end to the showdown.

Analysts say the protests don’t present a threat to Erdogan’s tenure, but threaten his legacy. Some say he has ambitions to enter the history books as a contemporary answer to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the founding father of modern Turkey.

Erdogan has reiterated his support for Turkey’s secular democracy in the face of the accusations of authoritarianism – and sat in front of a portrait of Ataturk during the overnight talks at his residence in Ankara.

—

Eds: Onur Cakir in Istanbul and Jamey Keaten in Ankara contributed to this report.