Don’t want your mug shot online? Then pay up, websites say

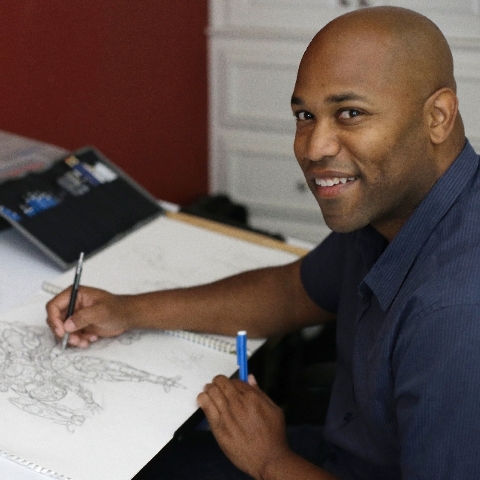

After more than seven years and a move 2,800 miles across the country, Christopher Jones thought he’d left behind reminders of the arrest that capped a bitter break-up. That was, until he searched the Internet last month and came face-to-face with his 2006 police mug shot.

The information below the photo, one of millions posted on commercial website mugshots.com, did not mention that the apartment Jones was arrested for burglarizing was the one he’d recently moved out of, or that Florida prosecutors decided shortly afterward to drop the case. But, otherwise, the digital media artist’s run-in with the law was there for anyone, anywhere, to see. And if he wanted to erase the evidence, says Jones, now a resident of Livermore, Calif., the site’s operator told him it would cost $399.

Jones said he was angered by the terms of the offer, but no more so than scores of other people across the country discovering that past arrests — many for charges eventually dismissed or that resulted in convictions later expunged — make them part of an unwilling, but potentially enormous customer base for a fast-proliferating number of mug shot websites.

With a business model built on the strengths of technology, the weaknesses of human nature and the reach of the First Amendment, the sites are proving that in the Internet age, old assumptions about people’s ability to put the past behind them no longer apply.

The sites, some charging fees exceeding $1,000 to “unpublish” records of multiple arrests, have prompted lawsuits in Ohio and Pennsylvania by people whose mug shots they posted for a global audience. They have also sparked efforts by legislators in Georgia and Utah to pass laws making it easier to remove arrest photos from the sites without charge or otherwise curb the sites.

But site operators and critics agree that efforts to rein them in treads on uncertain legal ground, made more complicated because some sites hide their ownership and location and purport to operate from outside the United States.

“The First Amendment gives people the right to do this,” said Marc G. Epstein, an attorney in Hallandale, Fla. who said he represents the operator of mugshots.com, which lists an address on the Caribbean island of Nevis. “I don’t think there was ever a First Amendment that contemplated the permutations of communication that we have now.”

Operators of some sites say they’re performing a public service, even as they seek profit.

“I absolutely believe that a parent, for instance, has a right to know if their kid’s coach has been arrested. … I think the public has a right to know that and I feel they have a right to know that easily, accessibly and not having to go to a courthouse,” said Arthur D’Antonio III, CEO of justmugshots.com, a Nevada-based site that started in early 2012 and now claims a database of more than 10 million arrest photos. But critics are skeptical.

“I can’t find any public interest that’s served if you are willing to take it (a mug shot) down if I give you $500. Then what public interest are you serving?,” said Roger Bruce, a state representative from the Atlanta area who authored a law, set to take effect July 1, requiring sites to remove photos free for those arrested in Georgia if they can show that charges have since been dismissed.

Scott Ciolek, a Toledo lawyer who last year brought a lawsuit against four sites on behalf of two Ohioans dismayed to find their arrest photos online, said the mug shot publishers are taking advantage of people’s embarrassment to unfairly squeeze them for profit.

“The individuals who are victims of these extortions want as little attention on them as possible, if you know what I’m saying,” Ciolek said.

The mug shot sites are just the latest ventures harnessing the Internet to aggregate information that previously would have taken considerable time, trouble or expense for ordinary people to uncover.

Arrest records are also widely considered to be public information and have long been collected by reporters making the rounds of police stations and courthouses. But before the advent of the web, an arrest on a charge of, say, disorderly conduct might have been printed in a local newspaper’s police blotter and then mostly been forgotten.

The mug shot sites’ operators use “web-scraping” programs to easily collect information from scores of police websites — and as a Texas lawsuit filed by one site operator against another shows, sometimes even to snatch those same photos from competitors. What used to be strictly local is now global, and a new tension results: Release of information widely regarded as necessarily public is, in aggregated form, viewed as potentially violating privacy.

“Certainly the world has changed in terms of the accessibility of historical information,” said Jeff Hermes, director of the Digital Media Law Project at Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society. “My concern is that efforts to create a so-called ‘right to be forgotten’ run the risk of becoming laws that allow individuals to edit history, and that’s dangerous, especially if it winds up being applied to public governmental records.”

But some of those whose photos have turned up on the sites say charging people to erase the evidence of an arrest is abusive.

Phillip Kaplan, one of the two people who brought the Ohio lawsuit, said he thought he had moved past the embarrassment of June 2011 when police, responding to complaints of a loud porchfront party he was attending during the city’s Old West End festival, charged him with failure to disperse. Kaplan, who is 35, said he declined an offer by prosecutors to plead guilty to a lesser charge, and eventually the case was dismissed.

In the meantime, though, Kaplan walked into a convenience store to find his mug shot on the cover of the weekly Buckeyes Behind Bars, alongside the headline “Hot Summer for Sex Offenders.” The publication says on its website that it charges $59 to those who’ve been arrested and want to avoid having their photo printed. Soon after, friends told him his mug shot was published on some of the online sites and later he was asked about the arrest during a job interview.

Kaplan said he understands the value to the public of publishing arrest photos, particularly for sexual predators. “That makes sense,” he said, but not for lesser charges. “I mean, should there be a jaywalkers’ directory?”

Jones, whose April 2006 arrest by sheriff’s deputies near Orlando, Fla., turned up online, said he suspects the availability of his mug shot might be affecting his search for employment.

“I’ve been putting out so many résumés and people’s reactions are just funny. They’re really excited, they’ve seen my résumé somewhere and then all of a sudden it’s like I have an infectious disease,” said Jones, who is 34 and now a college student in California.

The lawsuit filed on Kaplan’s behalf, though, does not go after the websites for posting the photos. Instead, it accuses the sites of violating Ohio’s publicity rights law by wrongfully using people’s images for commercial purposes. Ciolek, the lawyer, said he’s fielded more than 20 calls a day from people interested in joining the suit since filing it last December.

A separate suit by a Sicklerville, N.J., man, Daryoush Taha, filed in U.S. District Court in Philadelphia in December, charges that officials in Bucks County, Pa., failed to remove a 1998 mug shot taken after police intervened in a parking lot dispute between Taha and his girlfriend. Taha accepted placement into a program called Accelerated Rehabilitative Disposition and after completing community service in 2000 his record was automatically expunged. But his photo remained on the jail website and in 2011 was republished by mugshots.com.

“Listen, the whole purpose behind having your records expunged is to give you a second opportunity when you make a mistake,” said Alan Denenberg, the lawyer for Taha in the suit against police, other agencies and the website. But Denenberg said that while he had served the suit on a Delaware firm that registered mugshots.com as a limited liability corporation in the state, he has no idea who owns the website or where it operates.

The mugshots.com site says it is owned by Openbare Dienst Internationale LLC — a name whose first two words are Dutch for “public service” — and lists an address in Nevis that belongs to a different corporate registration agent. People who want to remove their arrest photos are directed to a link for a partner, Unpublish LLC, which lists the address of yet another registration agent, in the South American country of Belize. A phone number for Unpublish, listed on its Internet domain paperwork, rings to a fourth registry agent, also in Belize.

Epstein, who says he handles some public relations functions for the site as well as providing legal counsel, would not provide details of its ownership or location and a message left for the operator with one of the Belize agents was not returned.

“We know we’re going to be talked down. We understand it. Nobody likes meter maids, nobody likes traffic tickets and nobody likes mug shots, but we operate legally and in the realm of what we do, totally accurately,” Epstein said.

A competitor, mugshotsworld.com, lists an address in Russia, with a number on its registration paperwork that rings to a fax machine.

D’Antonio, who said he started justmugshots.com while working as chief technology officer of a Minneapolis web marketing company and recently relocated to a Nevada city he would not identify, was otherwise forthcoming.

He said he started the site after a friend asked for help manipulating web searches to “push down” a mug shot from his arrest on an alcohol-related charge. D’Antonio said that, in the process of doing so, he looked into the law covering mug shots, discovered they were public information and realized that, with his computer skills, that presented a business opportunity.

But he acknowledges that publishing the photos and charging people to take them down contradicts the sentiment of helping his friend. He said he has tried to act responsibly by removing photos at no cost for those who can show all charges have been dismissed, they were found not guilty, were under 18 at the time or for those who have since died.

“Then it becomes a balancing act and it’s a very, very tough line to walk and one that we absolutely take very seriously, but there’s very little black and white to it,” D’Antonio said. He said he expects the business of aggregating and publishing largely overlooked public records to evolve rapidly .

Some of the mug shot sites list numerous affiliated sites, often breaking down arrests by state. Bruce, the Georgia legislator, said calls to numbers listed on some sites were answered by what sounded like the same person, prompting concerns that a payment to erase a photo from one site might prompt the same photo to turn up on another.

But Epstein, the Florida lawyer, said the site he represents is “not Whackamole-y. You don’t hit the head down in one portion of the arcade game and it pops up somewhere else. That’s not our model at all.”

The new Georgia law attempts to curb the for-profit mug shot sites, requiring them to remove photos at no charge for those who were arrested in the state and can prove charges are dismissed, an idea that site operator D’Antonio said he supports. But the legislator acknowledges the law’s protections are limited in scope and its effectiveness will become clear only when it is tested in court. Some of those whose arrest photos have turned up online, though, see little recourse for their frustration.

Nicholas Ingebretsen, a college student in Savannah, Ga., is anything but proud of his arrest this past February, charged with disorderly conduct for throwing an empty bottle in a parking lot outside a bar. When a police officer asked what he was doing, Ingebretsen said he replied, “being an idiot, I guess.”

But when his mug shot showed up on three different commercial sites, Ingebretsen said he was mortified. He heard about Bruce’s bill and called one of the sites to request removal of the photo without charge. But the person who answered told him repeatedly that the website was exempt from the Georgia law, he said.

“They said read the bill. I said I did read the bill,” Ingebretsen said.

“I’m not going to argue with you,” the man on the other end of the line answered. Then he hung up.