Mayme Stocker

Not all the pioneers of the Las Vegas casino business were mobsters. In fact, Las Vegas’ first lawful casino license was held by Mayme Stocker, a wife and mother so respectable her birthday parties were covered in the Las Vegas newspaper society pages. She didn’t have any personal background in the gaming business, either. She was a decent working-class woman who didn’t have many chances to get rich, but managed to bet on the right one.

“Anybody who lives here is out of his mind,” was the remark she recalled making on her arrival in 1911. She remembered it 37 years later for a Review-Journal reporter who interviewed her as one of the community’s pioneers.

Born in 1875 in Reading, Pa., she was the daughter of a railroad man and married one at the age of 16. Mayme and her husband, Oscar, had three sons, Clarence, Harold and Lester.

The family moved from town to town in pursuit of railroad jobs — eventually to Las Vegas. Most of the moves were involuntary. Railroads in those days transferred their employees, hired them, and fired them, at will. In one case when the Southern Pacific laid off 100 of its employees, including Oscar Stocker, those laid off were paid in scrip, rather than cash, and not all stores accepted it.

So when Oscar got a job as an engine foreman in the Las Vegas railroad yards, the family was tired of moving every couple of years. They vowed to stay in their new home as long as they could, even if it turned out to be on the doorstep of hell. Which it pretty much seemed to be.

“There were no streets or sidewalks, and there were no flowers, lawns or trees,” Mayme recalled in the 1948 interview. In the hot summers, she said, “A familiar scene was the family groups hiking to the ‘Old Ranch’ for picnics and a few hours of relaxation in the shade of the large trees there. The older children in the family were usually seen pulling the younger tots in small wagons along the dust-covered trail made by horse-drawn vehicles.”

She could recall only three forms of public entertainment: “Ben Emrick and his four-piece German band, which played on the street corners on Saturday night … Ladd’s swimming pool on East Fremont Street, and the Princess theater, where a 5-cent movie could be viewed.”

There were no street lights and a walk downtown at night required carrying a lantern. “After a rain the walk was unpleasant because of the puddles of water left in the street. Ground, which appeared to be firm by the light of a lantern, often turned out to be wet and slippery, a hazard to a woman wearing a long skirt.”

Family duty rescued her temporarily from the boredom that was Las Vegas; a few months after her arrival, she learned that one of her two sisters in Butte, Mont., had not much longer to live. Mayme Stocker went to care for her and took along her son, Harold, then 11. It was a fateful trip, for it provided little Harold an introduction to the whiskey business. “Both my aunts were married to saloon owners on opposite sides of the street,” Harold Stocker recalled in 1981.

“One made a lot of money in Prohibition; he bought three carloads of liquor for 50 cents a quart, just before Prohibition went in. The people sold it cheap because Prohibition was coming, and my uncle bought it because he didn’t believe they would ratify Prohibition. When they did, he was stuck with it. Three years later he sold it anyway, and he got $25 a quart.”

In the meantime, Harold had moved back to Las Vegas. Then the local school burned down. Since the family worked for the railroad and could commute free, Mayme took Harold to Los Angeles and enrolled him in school there.

“I went to work as a dealer one summer, met somebody who got me a job in a casino in Tijuana,” Harold told the Review-Journal in 1981. “I was only 17, but it wasn’t illegal; there was no regulation there at all. I started out stacking chips at a roulette wheel. That was the game that had the most play in those days. That and ’21,’ which we dealt with gold coins and big pesos.

“There was a movie producer in L.A. who went down there to play, and he staked me to $500 to play in a ’21’ game while he went over and played pan. I’d bet $5, which was the minimum, till I had a hand, and then I’d bet $100. And if I lost, I’d go back to $5. When the summer was over, my cut was $6,000. A lot of money for a 17-year-old.”

When World War I broke out Harold joined the Student Army Training Corps, and was pulled out of school for active duty in coastal defense at San Pedro, Calif. “Then the flu bug came along and closed all the schools … I never did finish. I came back here in 1919 and went to work in the railroad shops.”

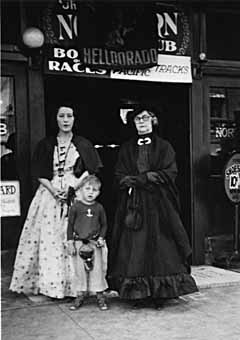

In 1920 Mayme Stocker opened the Northern Club, which would become a landmark on Fremont Street. Ostensibly a soft-drink emporium, its real mission was betrayed by its name. Virtually every town born during Nevada’s mining booms of the early 20th century had a Northern Saloon, and some of them still do. The name was supposed to appeal to veterans of the earlier gold rushes to the Yukon and Alaska.

Mayme Stocker was the original licensee, explained Harold, “because railroad men weren’t supposed to have anything to do with things like that.” Oscar and all three of his sons were connected with the railroad or aspired to be, since the railroad was the main local employer.

But Harold was part of the Northern from the start, and according to him, so was gambling. “She told me to come in and work because I knew how to deal, from Tijuana. There was hardly anybody who knew how in those days.” The Northern was a respectable place, but Harold also invested in some of the sawdust joints of Block 16. Some of these were only bars, while some were gambling houses and de facto brothels. (Harold said the usual arrangement was to rent rooms to attractive women, who did whatever they wanted in the rooms. The usual mode of getting acquainted was to buy the lass a drink, which contained no alcohol. The woman and the bar split the 50-cent proceeds from her drink, and that was the only profit the establishment made from her business.)

Although legal gambling is usually considered to date from 1931, said Harold, five games were legal in the 1920s — stud, draw and lowball poker, “500,” and bridge. No other games were then offered in Las Vegas, he said. “We had a tough sheriff then, Sam Gay. You could do it if it was in the book, and if it wasn’t, you couldn’t. I never gave anybody bribes but Sam couldn’t be bought anyway; he wouldn’t take a nickel from Jesus Christ.

“Sam Gay was against everything but whiskey … That was up to the federal government, and Sam left it to them.”

Percy Nash, Las Vegas’ chief of police, was not so easy to deal with. “I used to keep only one bottle of whiskey behind the bar, and that was in my pocket,” remembered Harold. “I could get rid of it quick, and if the prohis did catch me, they could get me for possession, but not for sale. Well, one day Percy Nash said he was going to jump over the bar and grab my bottle.

“I told him, ‘Percy, I got a .45, and if you jump that bar I’ll put one in your belly.’ ”

Percy Nash didn’t jump.

Harold Stocker was a law-and-order Republican, but figured that Nash, a local officer, had no business enforcing a federal law.

Another safety measure Harold took was never serving any drinks that weren’t mixed. “That meant that to prove it had whiskey in it, they’d have to have it analyzed. That was a lot of expense and trouble for a $200 fine.”

Harold Stocker was a partner in a distilling operation. “We made it in some natural caves out near where Vo Tech is … made good whiskey, bourbon bell… Aged it about three months in oak casks.” The operation used a copper pot still, noted for making the highest quality of moonshine. It produced more than the Stocker clubs could sell, and other retailers bought the surplus.

Harold’s older brother, Lester, was a professional gambler, and Harold credits him with getting wide-open gambling legalized. “He tried in 1925 and couldn’t get it open, and he couldn’t in ’27 or ’29.”

The rural counties weren’t interested in legalization, Harold Stocker told an interviewer in 1967, because the anti-gambling statutes weren’t enforced there, and gambling was already wide open. But conditions changed about 1930, when some big-shot Reno gamblers were sent to prison. Enforcement became less lenient.

“So in 1930 Lester called a meeting at a back table of the Northern. Not a back room, but a back table.” Present were some club owners, a city councilman, a high state official, a businessman booster, and two assemblymen, all of whom Harold Stocker declined to identify for the 1981 interview. One of them said, “If I had some money to spread around I could probably get it on,” Harold related.

Most of the $10,000 required came from the Stockers and their partners, primarily Lester Stocker, said Harold. “So they got the legislator from Winnemucca, Phil Tobin, to introduce it, and the fellow took the money. I don’t know who he gave it to. I don’t know if he gave it to anybody. But the bill passed.”

Assemblyman Tobin said all he made out of it was three bottles of scotch. He didn’t want to make money out of it. “I was just plumb sick and tired of seeing gamblin’ going on all over the state, payoffs being made all over the place,” Tobin told an interviewer in 1970. He served in the Nevada Senate through 1935, and went home to spend the rest of his life as a buckaroo living in a bunkhouse. He died in 1976 at age 75.

Lester Stocker died in 1934. Oscar died in 1941.

Mayme Stocker handed off the day-to-day operation of the business to others thereafter, and it operated under a variety of names including the Exchange Club and the Rainbow Club. In 1945 she leased the place outright to Wilbur Clark, who changed its name to the Monte Carlo Club. Her son Clarence continued to operate the Northern Hotel, which occupied the second floor. She built an elegant home in Huntridge, and every year enjoyed a birthday party given by her sons and friends. She lived until 1972 and the age of 97. Clarence Stocker died in 1951.

Harold Stocker lived until 1983 and the age of 82 but, surprisingly, got out of the gaming business and the whiskey business about the time they became fully legal. “The Depression had taken all the profit out of it. Besides, I never liked the business,” he said.

Harold also wanted to develop some glass-sand claims he had at Overton. Mayme Stocker was his partner in those. He built and operated the Chief Autel Court, a brick motel at Fremont Street and Maryland Parkway, and an apartment building which was then the largest in the state. In the 1930s he served a while on the County Commission, mainly because nobody else wanted the job, he said. He was instrumental in rural electrification and fiscal reforms.

Harold was chairman of the Nevada Republican Party in the 1950s. He was a political maverick who advocated dividing Nevada into two states, with 12 counties in Northern Nevada and five in Southern. He also advocated legalizing practically all victimless crimes and specifically prostitution. If there was any lesson to be learned from the successful legalization of gambling, he said in 1981, that should have been it.

“They’re trying to lay all this crime we have today on the hookers and the pimps,” he said. “Well, if that’s the problem, why the hell don’t they legalize it so they can regulate it, as they basically did on Block 16? Regulating it is all you can hope to do, because they have never succeeded in eliminating it in a thousand years of trying.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full