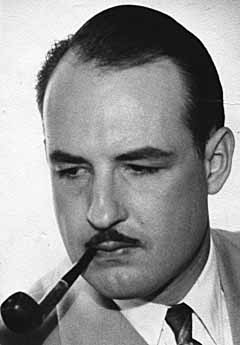

Maxwell Kelch

One morning in 1940, Maxwell Kelch answered his phone. The caller, an official with the Federal Communications Commission in Washington, D.C., apologized in advance for delivering the bad news.

The radio call letters Kelch had requested for his new station had already been assigned to a ship at sea. Kelch would have to settle for his second choice — KENO.

The FCC guy probably wondered why Kelch sounded so happy when he hung up. It was because he had got the call letters he really wanted.

“We leaped up and down and I cried,” recalled his wife, Laura Belle Kelch. “That was the name to have for Las Vegas. But we knew our illustrious Federal Communications Commission would never grant a gambling game name to a radio station.”

Laura Belle Kelch explained that the application form for a radio station license contained spaces for three choices of call letters. Certain KENO would be denied, they listed as their first choice KLVN. For their second, they picked KENO. Just for the hell of it.

Laura Belle Kelch also recalled seeing a mountain bluebird land outside her window just after they had received the news, and she took it as an omen of good luck. But it was vision and energy, not luck, that advanced the fortunes of Maxwell Kelch and his family.

Vision brought Maxwell Kelch to Las Vegas to found the valley’s first radio station. Energy and business acumen placed him at the forefront of the postwar push to make Las Vegas one of the world’s best-known destinations.

“If we trace the ancestry of efforts to publicize Las Vegas as a tourist attraction,” says Michael Green, a professor of history at the Community College of Southern Nevada, “then Max Kelch is the founding father.”

The son of a Los Angeles lawyer, Kelch was born there July 17, 1911. He grew up on Hollywood Boulevard at a time when that star-studded street still had lima bean farms.

By the time he was in high school, he was already licensed as a ham radio operator, spending his evenings chatting with other hams all over the world.

In 1933, he earned a bachelor’s degree in physics from UCLA, and set his sights on becoming a college professor. His amateur radio license helped finance his education, landing him engineering jobs at several Los Angeles radio stations. In 1936, he received his master’s degree in physics from the California Institute of Technology.

Kelch was having second thoughts about a career in academia. The pay was lousy, and the job market was tight. “By golly, I couldn’t get a job,” he later recalled, “because teachers weren’t dropping out.”

On the other hand, opportunities for qualified technicians in radio, film and recording were abundant. Between 1936 and 1939, Kelch was an engineer at radio station KFWB in Los Angeles. It was associated with the National Broadcasting Network, Warner Brothers Pictures, and Decca Records. Kelch worked as a design engineer for Warner Brothers and was technical supervisor for such network programs as “Amos and Andy.” For Decca, he served as a recording engineer for artists such as Bing Crosby and Francis Langford.

Laura Belle Gang was a native of Cincinnati who had lived in New York before coming to Los Angeles. In the late 1930s, she met Kelch at KFWB. “I was doing dramatic parts for an acting group,” she said.

In 1939, when Kelch took the job of chief engineer at station KGDM in the Sacramento Valley city of Stockton, Laura Belle went with him. That same year, they crossed the Sierra to Carson City and were married.

They had already decided they wanted their own radio station by the time they were married. Kelch just needed to find the most promising spot to locate.

“We did a survey of the Southwest, because that’s where we wanted to live,” said Laura Belle Kelch.

That research revealed Las Vegas once had a radio station, KGIX, but it had gone off the air. No competition.

Further inquiries revealed that the local business community would support a new radio station. “I thought it was wonderful,” said Laura Belle Kelch, who was able to ride her horse downtown on errands. “I had never been in, or lived in a small town before.” Of course, Las Vegas lacked the cultural amenities of larger cities, and Laura Belle soon found herself up to her elbows in civic and service activities. She was active in improving the Las Vegas Library and, as an accomplished watercolorist, was a founding member of the Las Vegas Art League.

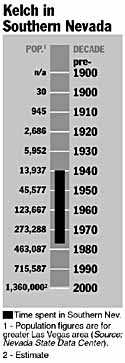

KENO went on the air in the fall of 1940, an ABC affiliate serving a population of only 8,700. “Included in the entertainment,” reported The Evening Review-Journal, “will be … ‘Our Scenic Southwest,’ devoted to promoting tourist interest in Southern Nevada and adjacent areas.”

KENO’s first broadcast facility was the old Meadows Club, which Laura Belle dubbed “The extinct nightclub.” It had been built in 1931 by gambler Tony “The Admiral” Cornero on the Boulder Highway at the site now occupied by Montgomery Ward.

The building itself was without heat in winter or cooling in summer, and was literally falling down.

Shortly after he opened El Rancho Vegas in 1941, casino man Tommy Hull made Kelch an offer he couldn’t refuse.

“Max, if I moved your radio station, your tower, everything, to my property, would you move over there?” he asked. Kelch agreed instantly. It was free studio space in a high-visibility location. Hull got a good deal, too. Every 20 minutes or so, the announcer would identify the radio station, and note that it was “broadcasting from the grounds of the fabulous El Rancho Vegas.” Later, Kelch built a new studio on the Strip, just north of where Circus Circus would later stand.

When the war started, Kelch reacted in the same way as most American men.

“He wanted to join the service and build radio stations abroad wherever they needed them, but they refused him,” says Laura Belle Kelch. “They told him he was more important here.”

And they meant it. An edict came from the feds requiring civilian radio station operators to carry sidearms while on duty.

“The essential radio service to everyone in the area was KENO,” recalls the Kelches’ son Rob. “It was where you tuned if there was an invasion on the West Coast. This was a tremendous scare; people really believed it was going to happen. They were afraid that if they had to evacuate the West Coast in an invasion, Las Vegas would be one of the staging points on the inland move where it would be very critical to have good radio commu- nications.”

And Southern Nevada was a prime target. A successful attack on Hoover Dam could have cut power to Southern California war industries. Basic Magnesium was another potential target, as was the Las Vegas Air Corps Gunnery School.

KENO was the community’s voice. Laura Belle Kelch, under the name “Peggy Maxwell,” hosted a program called “Listen Ladies,” which provided tips on the domestic arts and how to get the most out of ration books. Charles “Pop” Squires took the mike occasionally to recall some slice of local history, or to hold forth on his own brand of rock-ribbed Republicanism. Kelch even offered the Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal a slot to pass along the day’s headlines.

And, of course, he joined the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce. By 1944, he was elected president.

Rob Kelch attended many meetings with his father. Typically, he said, while everyone in the room was voicing opinions, Kelch would sit quietly taking notes. If numbers were bandied about, he would whip out his slide rule and check them.

“When everybody else had their say, he would come in and draw it all together; bring clarity to the situation, bring it to a point,” said Rob Kelch. “And more often than not, everybody would say, ‘Sounds good to me.’ He could summarize very well, and part of that was his mathematics background.”

Green notes that Kelch’s combination of intellect and market savvy was rare.

“The image of the scientist is of a guy tucked away in a lab with test animals, chemicals and a slide rule,” says Green. “Max Kelch stood that image on its head. Most people of an academic bent are not going to be as good at salesmanship as he was.”

The first idea Kelch sold to his chamber colleagues was that if Las Vegas was serious about wanting to build strong postwar tourism, it had to start planning before the war was over.

“Everybody is going to have to do their share to help bring the tourists and continued prosperity to Las Vegas after the war,” he told a gathering of merchants in the summer of 1944. “In short, we are going to have to stop paying more money to have our garbage collected than we have been paying to bring business to Las Vegas.”

Kelch conceived of Las Vegas as a product, like a box of soap or a car. And the way to sell a product was to advertise it.

“This was a quantum leap that really was Dad’s,” said Rob Kelch. “It was the first time the concept had been applied to Las Vegas.”

Kelch and the chamber budgeted $75,000 for publicity in 1945 and in February of that year, launched one of the most ambitious fund-raising campaigns in Nevada history, the “Live Wire” fund.

The “Live Wires” were chamber members who agreed to contribute 1 to 5 percent of their annual gross receipts for promotion. The large resorts pledged to match whatever amount was raised, up to $50,000.

UNLV history professor Eugene Moehring, in “Resort City in the Sunbelt,” said that Kelch and the chamber recognized “the crucial role played by propaganda in cementing support for the war.” They responded to the campaign accordingly.

“From its inception,” Moehring wrote, “the Live Wire campaign was a roaring success: $84,000 was raised that first year alone, with greater amounts thereafter.” The money allowed the agency to hire one of the nation’s largest advertising firms, J. Walter Thompson and, later, the legendary publicity agency of Steve Hannagan and Associates, which had engineered very effective campaigns for Miami Beach and Sun Valley, Idaho.

By 1950, the chamber could no longer afford Hannagan, but his techniques would remain. They would even be copied by other cities, said Don Payne, former manager of the Las Vegas News Bureau.

Payne credits Kelch with appreciating Hannagan’s genius and “borrowing” his modus operandi. “That’s why we named the Las Vegas News Bureau building in his honor and placed a memorial plaque at the front door,” says Payne.

In fact, Kelch’s ethical standards made him something of an oddity in the Las Vegas of the 1940s and 1950s.

He never ran for public office, nor invested in a casino.

The reason he resisted both temptations, explains his son, is that both were infested with people who could best be described as ethically elastic.

“There’s two businesses you don’t get involved in,” Max Kelch told his son, “one’s liquor, the other’s gaming.”

“It wasn’t that he had moral objections to it,” explains Rob Kelch. “He just thought that there were so many other opportunities, why get involved with businesses that tend to have a rather rough clientele?”

After selling KENO in 1955, Kelch got the local franchise for Muzak. He also designed and installed the public address system for the Pioneer Club that provided Vegas Vic, the club’s marquee-mascot with his two-word vocabulary, “Howdy Podner.” Rob Kelch was pretty sure his dad’s voice became the cowboy’s drawl that resonated down Fremont Street for decades.

A private pilot and a skilled boatman, Max spent part of every summer plying the Pacific Coast with Laura Belle in one of the three yachts they christened “KENO.” Kelch wrote a book on celestial navigation and taught it at the community college in the 1970s.

Both of Max and Laura Belle’s children remain in Las Vegas. Robert and his sister, Marilyn Gubler, operate a property management business and a gym.

Maxwell Kelch’s death in 1977 at age 66 was certainly a loss for this hometown, but his son also laments that his techno-crazed dad never had a chance to see the technology of later times.

“He would have loved computers,” says Rob Kelch. “He would be designing them by now.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full