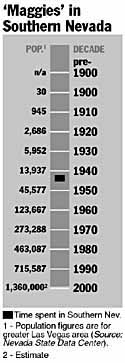

‘Magnesium Maggie’

Call her “Magnesium Maggie.” She was Nevada’s version of Rosie the Riveter, and she spent the war years making magnesium ingots, stacking and shipping them to the factories where they would be turned into tracer bullets and aerial flares and incendiary bombs for the machine guns and bomb bays of Allied aircraft.

Maggie never got the attention Rosie did, but Irene Rostine, herself a former war worker, vows Maggie won’t be forgotten. Rostine is gathering the stories of the women war workers, as her master’s thesis at UNLV and hopes to publish them in a book.

“I wanted to find out about them and put them in the public eye,” said Rostine. “There are movies about Rosie the Riveter and about the women who built ships in Seattle, and we had women who did something just as important,” she said.

She dubbed the women “Magnesium Maggies” because the largest group of them worked at the Basic Magnesium plant in what is now Henderson. But with the manpower shortages of war, women took jobs throughout the local economy, which had formerly been associated with men.

“At BMI they drove forklifts. They drove taxis, which were used to get around the plant because it was so big. They handled and wrapped ingots for shipping,” she said. Some made asbestos gloves to handle the ingots; some repaired gas masks.

The late Thelma Lindquist was called “Chlorine Kate” because she operated a cell that made chlorine gas, hydrogen, and caustic soda, which were used in the magnesium manufacturing process and also sold as byproducts. “Workers who ran these cells had to wear rubber shoes to prevent electrocution from the electrodes that were operating in the tanks of brine, and they had to carry a gas mask at all times,” said Rostine. “It was easily 130 degrees in that section in the summer, and in the winter it was so cold she would crawl up on top of the cells to get warm, even though it was dangerous and forbidden.” The job was so rough that most people who tried it lasted one day, but Lindquist stuck with it through war and peace, until her retirement in 1955.

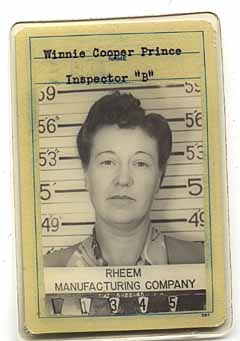

Magnesium production shut down in 1944, but portions of the huge plant were converted to other purposes. Rheem Manufacturing Co. rented the machine shop in May 1945, to make artillery shells and tracer ammunition.

Maxine Buckles worked then in a Boulder City bank. “I learned I could make as much money in a week at Rheem as I made in a month at the bank, so I applied,” she said.

She learned to operate a lathe, machining the shell down to exact size. “It wasn’t difficult work, but the shift was from 5 p.m. to 5 a.m. I got so I couldn’t sleep at night, I was so used to working.”

When the shell delivered to her for milling was too big, it would break the lathe. The worker who came to fix it, Benjamin Buckles, was an Army man employed there while on convalescent leave after being injured in the Pacific. He married Maxine before going back to finish the war.

Though many women married or at least dated men they met on the job, sexual harassment was rare. All the women interviewed for this story, and all those interviewed by Rostine, said neither they nor any of their friends had such problems.

Rostine thinks that may have been partly because Henderson was a company town, which did not blend into some larger society. “The town was built because of the plant, so everybody knew everybody. That would discourage it.” A town where most people were married, and where a would-be Lothario might run into a suspicious spouse at his own job or in the local bar, was a poor place to rustle up an affair, so it appears few tried.

Women’s previous life experiences adapted them to the work, in some ways better than men, suggested Rostine. “The metalworkers section at Basic was very dangerous, working over molten metal. But one woman said, ‘It’s nothing more than working over a hot cookstove.’ ”

The women’s safety record was better than the men’s, but they tended to get hurt in different ways. “They dropped things on their feet, or were hit by an object, or tripped. The kind of thing that happens to you when you are not used to a factory setting and find yourself in one,” said Rostine.

Economic opportunity was an important reason women worked in the war industries, but patriotism was also a strong motivation. Rostine’s mother-in-law, Della Mae Rostine, was a machinist, though so tiny at 90 pounds that she could not pull the safety cover down over her machine. Sometimes the cover sprang back and lifted her off her feet. “She complained to the foreman and he gave her a clipboard and made her keep track of downtime on the machines,” said Rostine. “But that was boring so she asked for a different job. The foreman said, `I don’t have a different one; if you want to help the war effort, you gotta do this.’ So she kept doing it, even though she hated it.”

Although Buckles worked in another war plant in Utah after the Henderson ammo factory closed, she was glad when the manpower shortage was over and she felt she could honorably quit. “I don’t want to do what men do,” she said. “I did it as a patriotic effort, but if they wanted me to do a man’s job now, I wouldn’t want to do it.”

She added, “I must say I really enjoyed the money, though. I saved what I could and went to school, to BYU. I had to drop out after a year because my mother became ill, but I really enjoyed that year.”

Winnie Prince, who also worked at Rheems, said, “I didn’t have any intention of staying (in the labor force). … We had a goal. We wanted to earn enough money to take our family to Salt Lake for the Centennial in 1947.” It was a goal she and her husband realized

Most of the Magnesium Maggies enjoyed their first taste of equal pay for equal work — generally 90 cents an hour for the Henderson production workers. Federal rules requiring equal pay, said Rostine, “were riddled with loopholes, but BMI apparently didn’t take advantage of them. All the women I found said they were paid the same as men.”

Even those who went back to the family cookstove, said Rostine, “cut a path for other women. They did jobs that were men’s jobs before.” By the time the war emergency was over, she said, there were women in most classes of jobs. While breakthroughs into management remained in the future, the door to industrial employment would never again be so tightly closed as it had been in prewar days.

Although the Henderson plants were the most conspicuous examples, said Rostine, much of Las Vegas economy was marshaled into support of the war, and wherever they could, women went to bat for their country.

Rostine herself made tail cones for B-17 bombers in New York before her family moved here in 1941. “I went to work for the telephone company, and that was considered war work because communications were so important. … Operators had to pledge not to disclose anything. You were under constant supervision, so it would have been hard to eavesdrop, but you might have overheard something.”

She parlayed her phone company experience into good postwar jobs setting up phone systems and supervising operators at several resort hotels. Later she owned her own business, Shamrock Realty.

Rostine was born in 1924 and graduated from high school in 1941, when a job in an aircraft factory seemed infinitely more important than a college education. She was past retirement age when she found time to enter UNLV, and was taking a class in social history when she decided to research women war workers.

She’s been at the task ever since. “I consider myself a local historian, trying to fill in the missing pieces in a puzzle. I feel that these women, who got up and went to work every day at a difficult job, helped make the community what it is. So without knowing about them, our understanding of the community is incomplete.”

Part II: Resort Rising