Las Vegas veteran recalls battles around Pork Chop Hill

Years after the 1953 truce that left the Korean peninsula divided, historians continued to call the United Nations police action that led to the stalemate a “conflict” instead of a “war.”

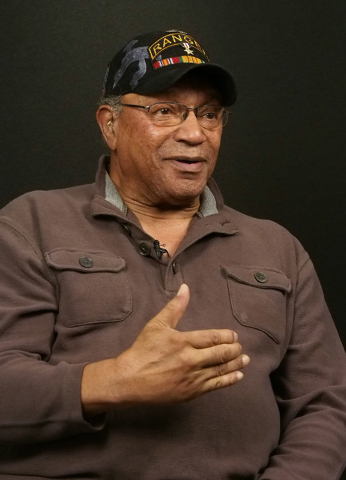

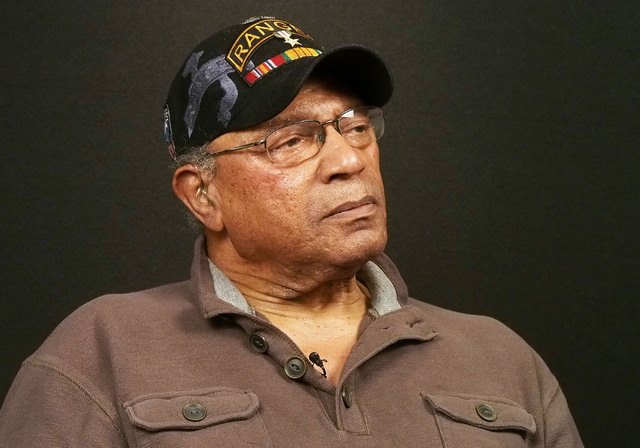

Sixty years later, nobody will ever convince Army veteran William “Bill” Miller that it wasn’t war. He was there. He fought it. Many of his friends in Love Company died in famous battles in and around Pork Chop Hill.

“It smelled like death. There was a lot of death,” Miller, 80, of Las Vegas, recalled recently in an interview. “We were trying to take the lives of the enemy and save the lives of the friendly.

“A lot of people died there. We had enemy and we had friendly. And they died,” he said. “We shed tears. We embraced each other and we prepared for the next battle. We don’t give up and we didn’t give up.”

Miller was born for battle. As a black teenager growing up in Georgia, he wanted to be among the first to integrate the ranks of U.S. troops fighting in Korea. He was 17 when he persuaded his parents to sign for his enlistment despite his mother’s staunch objections. She invited World War II veterans to their home to try to talk him out of it.

Instead, their stories fueled his desire.

“The more they said, the more I wanted to go. I want to defend this country. I want to fight communism. I want the whole world to be free. So Mom finally signed.”

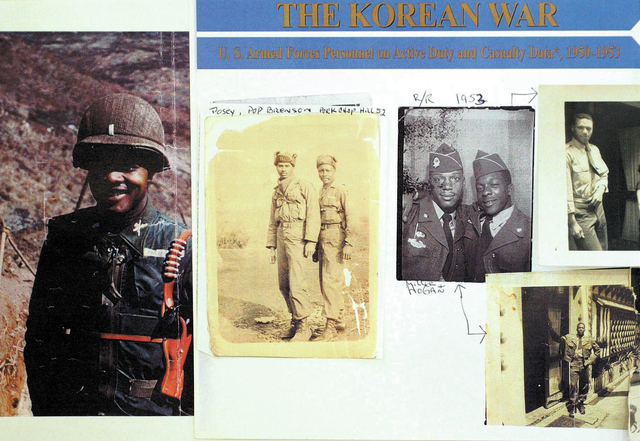

After airborne infantry training, he arrived in Korea in the summer of 1952 and was eventually assigned to Love Company — L Company, 3rd Battalion, 31st Infantry Regiment of the 7th Infantry Division. The company was commanded by a black officer, 1st Lt. Raymond Thompson, and fought in major battles of the Korean War. That included numerous times at Pork Chop Hill, a strategic outpost on the line of resistance where Chinese and North Korean soldiers had previously opened a path to Seoul, the South Korean capital.

Love Company had three rifle platoons and a weapons platoon that initially combined for about 150 soldiers of all races. But after battles on Pork Chop Hill in April and July 1953, its numbers dwindled significantly. In a five-month span, Miller’s field promotions boosted him from a private into the sergeant ranks.

“This is where the military was integrated. We just meshed and did the job as infantrymen,” Miller said. “We loved each other. We cared about each other. It didn’t make a difference where you came from. We just had men who could function, who could shoot, move and communicate. And men who were concerned about the man on his right and the man on his left. We refused to give in. You just keep shooting and keep firing. You never let the enemy take charge of you.”

One of the soldiers, Master Sgt. Edward Posey, began the war in December 1950 with the all-black 2nd Ranger Company, the first to integrate the 7th Division. His transfer to Love Company inspired Miller and others. He conditioned the younger soldiers by making them run up hills carrying five-gallon cans of water. After getting used to lugging the heavy cans around “you put on your bandoleers and rifle and you could fly,” Posey told the Review-Journal in a 2003 interview while visiting Miller who had recently moved to Las Vegas from Virginia Beach, Va.

Posey died this year, but his story is preserved in the book “Pork Chop Hill” by war correspondent S.LA. Marshall.

“The last thing you think about is getting killed. Getting killed is not really an option. I was never trying to be a hero,” Posey told Marshall.

Miller’s platoon fired mortars at the enemy around Pork Chop Hill from the rear of Hill 200. Much of their effort was devoted to setting up booby traps to dissuade enemy attempts to overrun the hill. They went on “contact patrols” to find and engage the enemy.

They supported assaults with fire from rifles, carbines and machine guns. They rescued wounded from the battlefield. They recovered the dead. They built and reinforced bunkers to protect them from enemy bombardments and to endure the freeze of winter and the summer heat.

Miller recalled his first day in Love Company on a smaller hill near Pork Chop Hill. “This young man got up and tried to go up that hill. There was fire and he rolled back down and he came to rest with his face in the dirt. I had seen my first death in the war.”

One time early in Miller’s deployment the company was pinned down.

“I got up and started up that hill. There was fire going but nobody hit me. I don’t know why. I’m waving to everybody else in the company. ‘Get up and charge.’ I got to the top of the hill as a private. When I came down for being a leader and trying to get others to move and not stay pinned down, they promoted me to PFC (private first class.)”

Miller said the attacking Chinese soldiers were tenacious. “You have to be prepared and we prepared for them, including fixed bayonets. We had a few people get involved in bayonet fighting.

“These guys were coming in waves. They were tough but we were tougher,” he said. “We were continuously under some form of enemy contact. So we had to say, ‘Why me? Why am I still standing? Why did that guy die and not me?’ I’m standing in front of a man talking to him. A round came in and he’s dead. I don’t even have a scratch. But that’s the way war is. You don’t know why but you continue to do your job.”

Miller made a career out of the Army. His awards include battle stars and medals for valor including a Silver Star Medal from his later days in Vietnam.

“I don’t have a victory medal and I wanted one,” he said, noting that the Korean War ended with an armistice agreement. “We did not win and I wanted to win. I didn’t get a parade. I didn’t get a victory medal. So, whatever. But I fought this war. Like a lot of young men we did it with dignity. We did it with pride. And then I had to go over to Vietnam and we didn’t win that war either. But the one thing I feel comfortable about is we integrated the Army and I became a leader, and teacher and trainer. I just don’t have the medal.”

Miller said Veterans Day means a lot to him. “I love veterans. I want to reach out with my arms and caress all of them. We should be setting examples for this country.

“Sometimes I lay in bed at night and think about the guys who were there with me and I shed a few tears.”

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.