Las Vegas Review-Journal killed story in 1998 about Steve Wynn sex misconduct claims

Claims that casino developer Steve Wynn sexually harassed employees could have surfaced years ago but the Las Vegas Review-Journal in 1998 stopped publication of a story that would have brought the issue to light. After killing the article, the newspaper ordered the reporter who wrote it to delete it from the newspaper’s computer system.

The Review-Journal’s decision came after Wynn’s attorneys met with the reporter and the newspaper paid for lie-detector tests for two women who alleged a culture of harassment at the Wynn-owned Mirage.

Allegations about Wynn’s conduct appeared in a Wall Street Journal story last month. Similar claims were made in a court filing in 1998.

In a lawsuit, a Mirage cocktail server alleged supervisors did not protect women from gamblers who harassed them. She said waitresses were sent to sexually “accommodate” high rollers at the resort’s luxury villas throughout the 1990s.

Another server, upon bragging about her first grandchild in the early 1990s, reportedly was pressured into having sex with Wynn, who said he wanted to experience sex with a grandmother, according to a court filing.

Two of the cocktail servers spoke to Review-Journal courts reporter Carri Geer in 1998. Geer said she remembers then-Publisher Sherman Frederick saying the women should undergo lie-detector tests.

Carri Geer Thevenot, metro editor of the Las Vegas Review-Journal. (Elizabeth Brumley/Las Vegas Review-Journal)

After the polygraph results came back, Geer, who is now the Review-Journal’s metro editor, said she was ordered to delete the story she had written. But she saved a printout of the story, the court records from the case, the polygraph results and the $600 bill for the polygraph examinations.

She could not recall who blocked publication of the story or who ordered her to delete it.

“I always wanted to tell these women’s stories. That’s why I saved this file for 20 years,” Geer said.

No memories

Indiana University law professor Jennifer A. Drobac said public disclosure of the women’s accounts — even in 1998 — might have created pressure to remove Wynn or force changes in his behavior, well before the birth of the “#MeToo” movement.

“Maybe he’s Mr. Teflon, but at least people would have known,” said Drobac, who has represented sexual harassment victims. “It might have made a difference in later business deals. The public would have understood that this guy has a questionable past.”

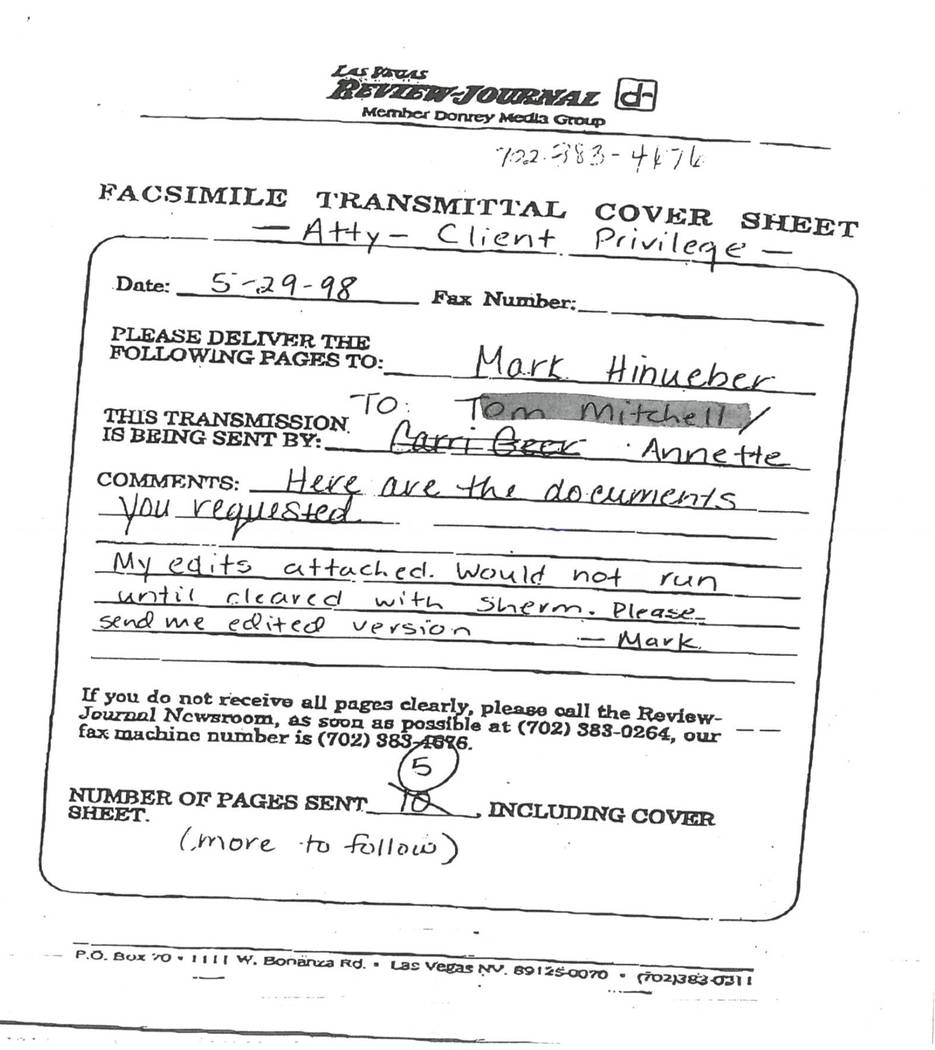

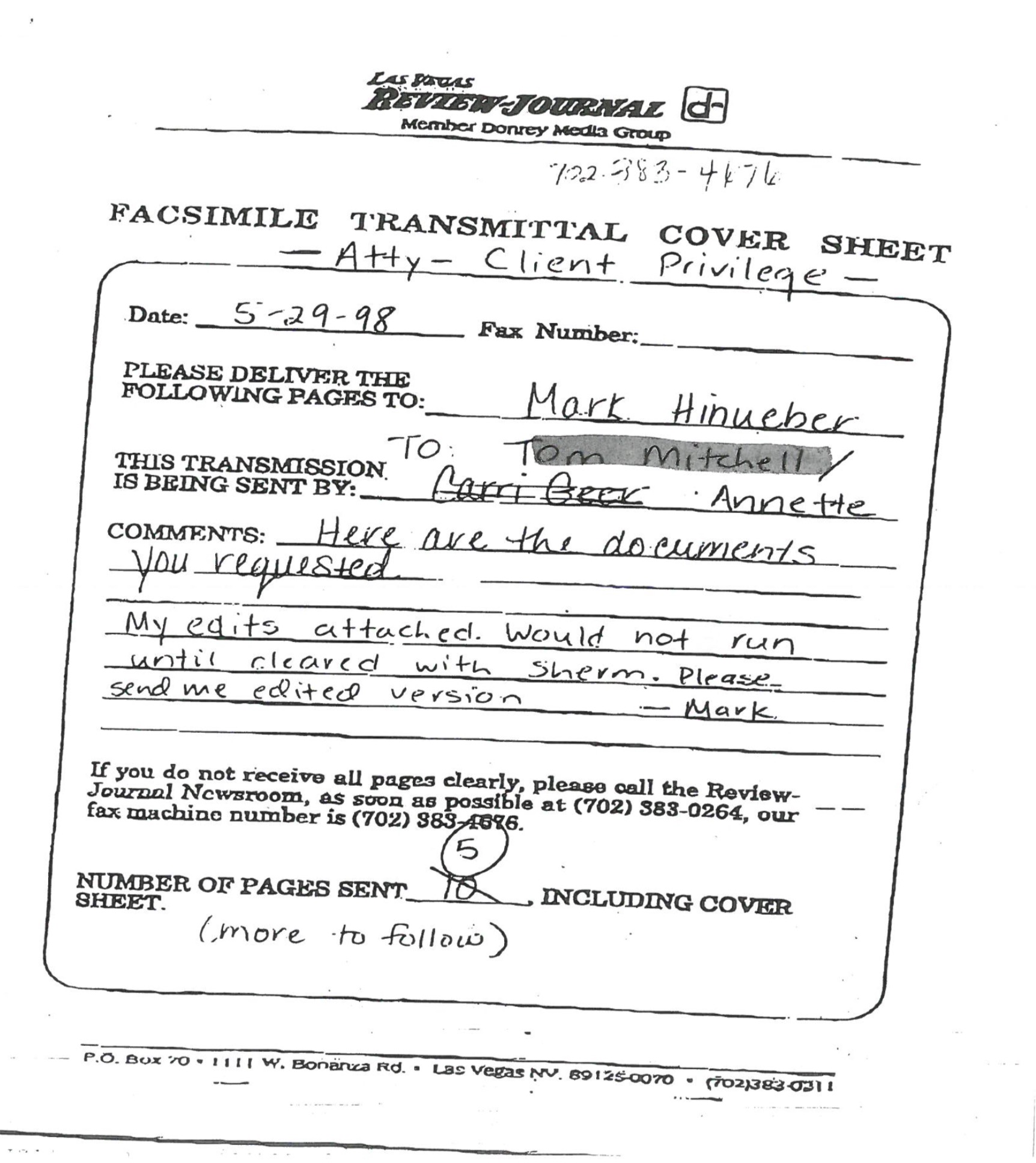

Review-Journal attorney Mark Hinueber reviewed Geer’s 1998 story for liability reasons. His edits, which were saved in Geer’s file, deleted key allegations from the story, including the account of the cocktail waitress who said she was pressured to have sex with Wynn and her supervisor’s warning that she would lose her job if she did not comply.

Hinueber wrote on a fax cover page, “My edits attached. Would not run until cleared with Sherm (Frederick).”

Hinueber, who continues to provide legal counsel for the Review-Journal, declined to comment, citing attorney-client privilege with the newspaper’s previous owners.

Frederick said Tuesday that he does not remember the story.

“You’ve lost me,” he said. “I don’t remember any of that. I certainly don’t remember paying for any polygraph tests.”

Polygraph examiner Ronald Slay, of Western Security Consultants, said a top official — he wasn’t sure who — from the Review-Journal showed up with the two women for the exam.

“When he showed up I knew this was a bigger deal than normal,” Slay said.

A 1998 Fax

Thomas Mitchell, editor-in-chief at the time, remembered the newspaper used polygraph exams for some sources but said he did not remember the circumstances.

“We looked into those sort of things but couldn’t nail them down,” he said. Mitchell said he didn’t kill stories because of pressure from others.

Kevin Doty, an attorney who worked for the newspaper at the time, said Mitchell asked him to set up the polygraph tests, and that Mitchell went with the women to the exam.

Geer said she was called into a meeting with Wynn’s attorneys in Frederick’s conference room as she was preparing the story in 1998. Frederick did not recall the meeting.

Discrimination lawsuit

The allegations against Wynn and The Mirage were laid out in a 1997 federal lawsuit. Eleven waitresses sued The Mirage, where Wynn was chairman at the time, after he allegedly told the servers they did not look good in their uniforms.

A policy change required them to maintain their weight at the time they were hired. His attorneys sent questions, known as interrogatories, to plaintiff Earlene Wiggins, and her answers, which were sworn and filed in court, described a culture of harassment, coerced sexual conduct and misconduct by Wynn.

Wiggins said in the court filing that baccarat players groped her and asked for kisses.

Wiggins also said in the filing that fellow plaintiff Cynthia Simmons had to “accommodate customers sexually.” Simmons told the newspaper in 1998 that she received between $1,000 and $5,000 from each customer in exchange for sex.

Another waitress was sent to the high-roller villas to have sex with a German gambler who was Wynn’s friend, Wiggins said in the court filing.

The Review-Journal published stories about the “fat meeting” and a subsequent lawsuit and Equal Employment Opportunity Commission complaint.

By 2003, The Mirage had settled all of the claims.

Polygraph exams for sources

The polygraph results suggested Simmons was being deceptive, but Wiggins, who was quoted in the court document, was being truthful. Wiggins died in 2006.

Simmons, now 60, said she was nervous during the lie-detector test.

“I was under emotional distress — I couldn’t even sleep the night before,” she said Tuesday.

She said she is upset that, despite support for her story in Wiggins’ sworn statement, the Review-Journal never published Geer’s article in 1998.

“It was hard enough to come forward in the first place and reveal this stuff to my family, and then to have the newspaper curb the whole story, I feel I got silenced,” she said.

Frederick said he would not have buckled under pressure from Wynn’s lawyers.

“Wynn, he’s a difficult guy, and it wasn’t unusual that he would call and yell,” he said.

Kathleen Culver, director for the Center for Journalism Ethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said she has never heard of a news organization requiring sources to take lie-detector tests.

“I feel it is a hefty demand of a source,” she said.

Slay, who administered the polygraph exams for the Review-Journal, said he often tested sources for publications like the National Enquirer but had not done so for mainstream news publications.

Culver said that accurately quoting a court document protects journalists against defamation claims.

The $600 bill for the polygraph examinations.

“Lawsuits can be really taxing on a news organization, and you can see why you would be afraid, but I don’t see why you would bow to that fear and spike the story,” she said. “Journalism has to be about courage.”

Wynn did not respond to requests for comment on the allegations against him and The Mirage. He has denied the allegations raised in The Wall Street Journal story.

“We find ourselves in a world where people can make allegations, regardless of the truth, and a person is left with the choice of weathering insulting publicity or engaging in multi-year lawsuits,” Wynn said last month in a written statement to the Journal. “It is deplorable for anyone to find themselves in this situation.”

Simmons said The Mirage culture outlined in court records was well-known to employees.

“I’m shocked anyone thought it was a secret,” she said. “We all knew this was going on, but nobody spoke up because they were afraid.”

Review-Journal staff writer Brian Joseph contributed to this story. Contact Arthur Kane at akane@reviewjournal.com. Follow @ArthurMKane on Twitter. Contact Ramona Giwargis at rgiwargis@reviewjournal.com. Follow @RamonaGiwargis on Twitter.

See all the Review-Journal’s coverage of the Steve Wynn story.