Irwin Molasky

Irwin Molasky works in a cylindrical building full of ferns, open staircases, photos of race horses and sports stars.

“It’s the kind of building that ought to be in the middle of a landscaped office park,” he quips. “But it’s in the middle of a parking lot so our tenants can find us.

“You see plans everywhere you look,” he pointed out to the visitor entering a spacious but cluttered office. “This is a construction office. A place to work.”

Molasky opens a conversation by establishing immediately the central theme of his life. He builds. He works. He’s been doing it since boyhood and is still going strong at 72.

Since 1951, he has done it mostly in Las Vegas. Outside those who built the most innovative Strip hotels, he probably has been Las Vegas’ most significant developer. He built Las Vegas’ first enclosed shopping center, Boulevard Mall; its first modern private hospital, Sunrise Hospital and Medical Center; and its best-known office building, the Bank of America Plaza. With Las Vegas partners he built the La Costa resort near San Diego, and started a successful television and motion picture production company.

His father was an Ohio businessman who had a newspaper distribution agency and managed apartment buildings. One of the most significant facts of Molasky’s childhood was attending a military high school, away from home.

“It made me independent,” he explained. “So I wanted to earn my own money from then on. I spent my summers working.” Because his brother-in-law was in construction, he entered the business as a teen-age gofer.

Molasky attended Ohio State for a year but decided to transfer to UCLA and moved to Southern California. “But I started construction jobs to support myself and I just never did matriculate,” he said. “I did everything. Waterboy, hauled lumber, estimating, then I took the plunge and started design and construction.

“I built my first apartment building when I was 19. I was too young to get a loan; it was either forge the papers or get my father to sign for me, and he signed. I didn’t know what I was doing but it was a big success.” The five-unit building still stands.

Molasky was drafted in the late 1940s but was discharged before the Korean War.

He moved to Las Vegas in 1951 to take advantage of the construction opportunities. Initially, he did small jobs such as garage conversions and home additions. A few years later he met Merv Adelson. The son of a Beverly Hills grocer, Adelson moved to Las Vegas to start Market Town, a 24-hour foodstore at Oakey and Las Vegas Boulevard South. They founded Paradise Development Co. which remains active today.

One of their first projects was Paradise Palms, the neighborhood bounded by Desert Inn and Flamingo Roads and by Maryland Parkway and Eastern Avenue. From 1957 through 1959, said Molasky, it sold a house every day for $30,000 to $40,000.

About 1956, said Molasky, the partners started thinking about constructing a medical building, but when they approached doctors to determine interest, “every one of them said, `We really need a hospital.’ ”

The main hospital in town, explained Molasky, was run by the county, and was a political football. “The doctors wanted out of the politics and also they wanted to practice with modern facilities.”

The hospital was originally financed by a local savings and loan business, said Molasky, “But we ran out of money and had to take in some investors.” The investors included Allard Roen and Moe Dalitz, both associated with the Desert Inn.

Sunrise opened its doors in December 1958 with 58 rooms; now it has 688, and is the largest private hospital west of Chicago, said Molasky. “We started the first heart transplant unit, the first children’s surgical unit; it has 28 surgical suites and 1,200 doctors on the staff.”

Molasky’s wife, Susan, sits on the hospital board. Molasky admits a “patriarchal pride” as well as gratitude when comes to the hospital. “One of my granddaughters had a problem at birth and that neonatal unit saved her life.”

After not doing well financially with professional hospital administrators, the hospital hired Nathan Adelson, Merv’s father, who had been in the grocery business.

“The doctors loved him,” Molasky said. “He brought ethical business practices with him. They kept him to run it long after we sold it.”

Molasky continued, “Nate Adelson died of cancer, a very inhumane death. We thought there must be a better way. We heard of a program in England, at a place called St. Christopher’s, where they taught people who are dying how to live their last years in dignity. So the university gave us a lease for a dollar a year to build this kind of facility here.”

Nathan Adelson Hospice was born. It takes all comers, said Molasky, regardless of ability to pay.

It was also through the hospital, Molasky said, that he came into contact with the Teamsters Central States, Southeast, and Southwest Pension Fund, which provided financing for some of his future projects.

“The local Teamsters, as well as the Culinary union, wanted us to take all their members for a certain amount a month. It was an early form of managed care. We needed more bed space to do this.” So local Teamsters loaned $1 million to expand the hospital from 58 to 120 beds.

The Teamsters also financed the famous and notorious Rancho La Costa development near San Diego.

The development loans, more than $100 million, had been made in an era when the pension fund was mob-influenced. After an investigation, Molasky said the federal authorities found nothing wrong with those loans.

Although Dalitz had conducted himself respectably since moving to Las Vegas in the 1950s, he was a former bootlegger and illegal gambler who had been publicly grilled in the U.S. Senate. His associate Roen had pleaded guilty to securities violations in a major stock fraud case in 1962.

Dalitz and Roen were partners in developing La Costa, but inactive. Neither Merv Adelson nor Molasky, the active partners, had ever been charged with a crime. Nevertheless, Penthouse Magazine published an article asserting the resort had been built and frequented by gangsters. “Penthouse made allegations that weren’t true,” said Molasky.

The four partners sued for libel. After years of litigation, they won no money, but Penthouse issued a letter saying it did not mean to imply that Adelson and Molasky “are or were members of organized crime or criminals.” The statement did not include Dalitz or Roen.

Molasky was involved in the development of most of Maryland Parkway from Sahara Avenue to Flamingo Road, including Boulevard Mall. Opened in 1968, it was the first enclosed mall in the valley. He also developed Best on the Boulevard, a smaller shopping center just south of the Boulevard Mall, concentrating on what he calls “big box” retailers such as Best Buy and Copeland Sports. He used the same concept in 1996 at the “Best In the West” center at Lake Mead and Rainbow boulevards.

About 1966, related Molasky, he and Adelson met Lee Rich, who produced TV shows for ad agencies and dreamed of producing TV specials and scheduled shows. Lorimar was born.

One of their first efforts was based on the work of a then-obscure Virginia author named Earl Hamner. “He came to us with this wonderful story about a family going through Christmas after the Depression,” recalled Molasky. The story became known to millions as “The Homecoming,” and spun off the enormously successful series “The Waltons.”

Lorimar also produced “Eight is Enough,” and the less wholesome “Dallas,” “Knots Landing” and “Falcon Crest.”

Lorimar’s feature films included “Sybil,” “Being There” and “An Officer and a Gentleman.”

Molasky is no longer involved with Lorimar. Adelson, who reportedly had wanted to be in the entertainment industry since his Beverly Hills childhood, became more and more associated with Hollywood; he even married Barbara Walters. Lorimar eventually merged with Time-Warner, and Adelson became one of its board members. But he continued to be active in Paradise Development until this year, when Molasky bought him out. Molasky says they are still friends.

Bank America Plaza was conceived when Parry Thomas, who then headed Valley Bank, contacted Molasky. “He said, `I want an image and a name to be seen for many miles around.’ He wanted prestige and he wanted a modern branch downtown,” remembered Molasky.

“I said, `The only way you can get that is a high-rise.’ ” Parry and Molasky purposely built it as the tallest downtown building, to dominate the skyline.

“It was a giant leap of faith. It was built in 1975, and it took years to fill it up,” said Molasky. “But I think it really helped economic development in downtown; I believe a lot of law firms would have migrated out without it.”

Molasky and Adelson also were key figures in the development of UNLV. “Parry Thomas came to me and said if we are to have an urban university, we have to have land.” The partners donated 45 acres off Flamingo Road and Maryland Parkway for the campus. “Again, he came to me and said every great university needs a foundation to help guide, to help subsidize a president and a good faculty, and I can’t think of anybody better than you to start it.” So Molasky started the UNLV Foundation, modeling it on foundations at other institutions.

He is still a member of the foundation, though he stepped down from the board years ago, during the administration of UNLV President Robert Maxson. “I did not like Maxson’s tactics,” said Molasky. He blames Maxson for escalating the conflict between athletics and academics, culminating in the resignation of coach Jerry Tarkanian.

The Molaskys became mentors to several of Tarkanian’s basketball players. On a place of honor on his wall hangs a picture of Sidney Green, a former University of Nevada, Las Vegas standout and NBA player, now a coach in Florida.

Molasky’s interests in sports have been more than casual. He was named as a member of “The Computer Group,” a ring of sports betters investigated and unsuccessfully prosecuted by the Las Vegas Organized Crime Strike Force. Molasky was given immunity but testified in the 1992 trial that he bet small fortunes. In 1982, he testified, he lost $30,000 betting baseball and won $350,000 betting football.

Molasky said the prosecution resulted from the government’s mistaking sophisticated bettors for bookmakers.

“The government indicted 10 or 12 people, mostly people I didn’t even know, and they were all found innocent.”

Does he still gamble?

“The biggest gamble you can get in this country is building a high-rise,” he chuckled. “I still do that.”

He has another hobby that he suggests is not so much gambling, as a very expensive hobby. He owns race horses.

“Racing is kind of a dying sport, but I get a thrill out of having a good horse,” he said. “They’re like athletes.” He owns the horses in partnership with the well-known trainer, Bruce Headley. One of Molasky’s horses is Kona Gold, acknowledged the nation’s fastest sprinter, though now rehabilitating from an injury.

He was formerly an avid golfer and tennis player, but quit both sports because of back trouble.

Molasky has been married twice, first to Pepi Bookbinder, a make-up artist he met in Southern California; they were divorced in 1969. In 1973 he married Susan Frey.

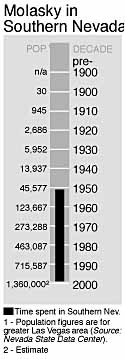

With 48 years invested in Las Vegas, Molasky is still plowing his energy and resources back in to the town, and does not think the phenomenon has run its course. “We have such infrastructure in this community now, billion-dollar hotels, white tigers and volcanoes, so I don’t see how any other community can compete with us just because of the spread of gambling. … I don’t think it will continue a 5,000-a-month growth rate forever, but I don’t think it will crash. … I see the city going to 2 million in the near future.

“The only thing that could blight that future would be slow growth or no growth policies some are trying to put in. … Managed growth, with good architectural controls, certainly we should have that, but not slow growth or no growth. Because who’s to say when the right time is to cut it off?”

Part III: A City In Full