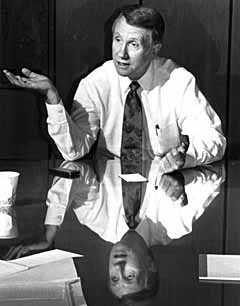

Harry Reid

The Las Vegas Spaghetti Bowl had been giving drivers heartburn for years, until Sen. Harry Reid bathed it in a soothing sauce of $45 million in federal highway funds. Remember that big hole in the ground? Reid spent three years rounding up $98 million to build a new federal courthouse in it.

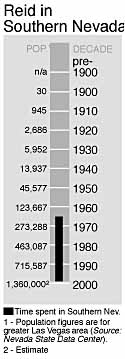

At the close of the century, Reid has emerged as the successor to Nevada Democrats such as Francis Newlands, Key Pittman and Pat McCarran, all of whom shared a talent for bringing home the federal bacon.

“His effectiveness for Nevada is his seniority, and the fact that in a relatively short amount of time, he has attained a fairly high profile,” says political analyst Jon Ralston, publisher of The Ralston Report. “He’s only been in the U.S. Senate since 1986, and he’s already in its second-highest position (minority whip). That’s really saying something.

“He’s not the most dynamic personality in the world; what he’s been able to do is build relationships. He’s willing to take on the grunt work that nobody else really wants and that earns him chits with the leadership and with members of the other party, too.”

Harry Mason Reid was born in Searchlight on Dec. 2, 1939, third of the four sons of Harry and Inez Reid.

The elder Reid was a hard-rock underground miner. Underground mining involves dynamite, and miners were frequently pelted by tiny rocks. Reid recalls watching his father sitting backward and shirtless in a chair while his mother scanned his back looking for stony outcroppings.

“They would work their way to the surface,” Reid explains, “and my mother would pick them out as they did.” As a grade-school kid, young Harry, with his own helmet and carbide lamp, would go underground to keep his father company. As he got older, he worked alongside him.

“I never did any drilling, but I ran the hoist on a lot of occasions, and I did a lot of mucking.” Mucking is the back-breaking job of shoveling rock dislodged by dynamite into an ore cart.

The senior Reid was a tough, independent man possessed of a strong work ethic. By 1972, his health failing, he could no longer work. The reality of never again being productive was more than he could bear, and when his wife stepped out on an errand one day, he fatally shot himself.

Inez Reid taught her boys that despite their humble homelife, they were as good as anyone, and could reach any station in life if they had the ambition, something that is a “primal instinct” for Reid, according to Larry Werner, a former Review-Journal reporter who later worked for Reid as his press secretary.

Reid attended Basic High School in Henderson, where he boarded with a family. It was at Basic that he met Landra Gould.

“She was a sophomore and I was a junior,” says Reid. “We started dating and we’ve been together ever since.”

In his senior year at Basic, Reid was elected student body president, and met his new history teacher, a big Irishman who had lost a leg in Korea. Donal “Mike” O’Callaghan would loom large in Reid’s future.

Reid graduated from Basic High School in 1957, and earned an associate of arts degree from Southern Utah State College in 1959. That year, he married his high school sweetheart. She was Jewish and Reid was unchurched, but shortly after their marriage, both joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In 1960 and 1961, the first of their five children were born.

“She gave up most of her education to put me through school,” says Reid. “I’m the one who should have worked and let her go to school. She’s much smarter than I.”

O’Callaghan kept in touch with his former pupil, providing advice, encouragement, money and the benefit of his burgeoning political power.

On a scholarship arranged by O’Callaghan, Reid attended Utah State University in Logan, where he had a dual major in history and political science, and graduated in 1961 with a bachelor’s degree in both.

That year, O’Callaghan, then chairman of the Clark County Democratic Party, wrote to then-Congressman Walter Baring, asking if he could arrange a patronage job in Washington for his young protege, who was enrolling at the George Washington University School of Law. Baring wrote back, essentially giving O’Callaghan the brush. To make matters worse, he had misspelled O’Callaghan’s proud Celtic name.

Reid was present when O’Callaghan received the letter, and watched as he picked up the phone, dialed Baring, and verbally terrorized him for several minutes.

“What right do you have to write a letter to me and not even spell my name right?” roared the big man. “This is one of the best kids I’ve ever had and you’re telling me you don’t have a place for him?” In short order, Reid was sporting the uniform and badge of a Capitol policeman, and enrolled in law school.In 1963, with another year of school to go, he petitioned the Nevada Supreme Court to allow him to take the state bar examination, offered only once a year. The court approved Reid’s request, he flew home, and was met at the airport by O’Callaghan, who pressed a green bill into his hand.

“It was the first $50 bill I had ever seen,” says Reid. “He is a … disabled veteran, and his pensions have always gone to students. He helped pay my way through law school.”

In 1964, when he graduated, Reid was licensed to practice law in Nevada, and the family returned to Henderson where, as the first resident to graduate from law school, he was appointed city attorney. Reid also maintained a private law practice.

One day, the young barrister went before the Southern Nevada Memorial Hospital Board with his client, a physician who had been accused of some professional transgression.

“The chairman of the board of trustees came out, looked at us, and said, “We don’t need lawyers around here; we do what we want to do.’ ” Reid was offended by the man’s arrogance, and after determining that his was an elected post, successfully ran against him, serving as hospital board chairman 1966-68.

Brimming with confidence, Reid decided in 1967 to run for one of Clark County’s 18 seats in the Assembly.

“I picked a fight with the phone company — service was so bad then — and they were dumb enough to respond to me,” says Reid. “So I had an issue.” Reid was the top vote-getter among the 18 people who won seats in the 1968 Assembly, and one of only two freshman elected that year. The other was Richard Bryan.

That year, the public got a look at the Reid work ethic. He churned out bills like a mucker being paid by the ton.

“I hold the record for introducing more bills in a session than any one person in history,” says Reid. “I didn’t get many of them passed, though. I think the most important thing I did in that session of the Legislature is pave the way for others to adopt legislation that I introduced.”

Reid says he introduced the state’s first air pollution bill, and another to force utilities to pay interest on the large deposits they levied on ratepayers. Both have since become law.

Reid proved Jimmy Breslin’s assertion that politics is “all smoke and mirrors” in the 1970 race for lieutenant governor against Robert Broadbent.

“I didn’t have organization, and I had very little money, but people didn’t realize that,” says Reid. “People thought that Howard Hughes was behind my organization, and I never lied to anybody and said he was, but I never said he wasn’t, either. It was one of my easier elections.”

Surprising, too. His old mentor, O’Callaghan, was the Democratic nominee for governor, facing an “unbeatable” Ed Fike, the outgoing lieutenant governor.

“I was favored to become lieutenant governor; he had no chance when he filed as governor,” says Reid. What no one had anticipated, though, was that in the midst of the campaign season, Fike would become embroiled in a conflict-of-interest scandal over his purchase of government land along the Colorado River while in office.

“It was just fortuitous that he became governor when I became lieutenant governor,” says Reid, who, at age 31, was the youngest lieutenant governor in the state’s history.

“I was not only young,” says Reid, “I looked young.” The Boy Lieutenant Governor wore garish “mod” clothes, affected a set of Elvisian sideburns, and wore his hair long.

“There has never been a governor and lieutenant governor that worked more closely than we did,” says Reid. “There was never a meeting he didn’t invite me to, I knew everything.”

And though O’Callaghan’s job was full time, and Reid’s part time, the hard-charging governor expected everyone around him to work as hard as he.

“It was a very grueling four years,” says Reid. “O’Callaghan had no clock in his head, he had no idea what time it was, day or night. He would call me at 3 in the morning as if it were 3 in the afternoon,” says Reid. “To this day, I can dial a telephone in the dark of night.”

Veteran Democrat Alan Bible announced he would not seek re-election in the 1974 senatorial race. O’Callaghan was expected to run, but didn’t, and Reid decided he was ready for national office. His opponent was Paul Laxalt, who had been governor when Howard Hughes came to Las Vegas in 1966.

Reid launched an aggressive, negative campaign, accusing Laxalt of profiting financially from his association with Hughes. Laxalt had indeed taken cash donations from the billionaire, but so had he, O’Callaghan, and virtually every other politician in the state. It was legal then. Reid, who would soon feel the sting of unsubstantiated attacks on his own integrity, says he now regrets his assault on Laxalt. Besides, it didn’t work. Reid says he resorted to hardball because he needed a high profile issue on which to campaign.

“I was like a fish looking for bait,” he says. “Every time he threw something out, I would snatch it.”

When the votes were counted, Reid had lost to Laxalt by a little more than 600 votes. It was the 35-year-old Reid’s first political loss, and he did not handle it well. In a rare public show of petulance, Reid accused the Northern Nevada press of unfair coverage, and costing him the election. The reply was swift and sharp.

“Reid lost because he ran the worst political campaign anyone can recall around here,” wrote Warren Lerude, then executive editor of the Reno Evening Gazette and Nevada State Journal. “All Reid didn’t say was that the press won’t have Harry Reid to kick around anymore.”

“I was young, impetuous, and I had never lost anything,” he says. “I might as well have blamed Nikita Khrushchev. It was just a sign of my immaturity. But it was one of the most character-building experiences of my life. I think I’m a better person for having lost that race, and I know I’m a better legislator.” Against the advice of all his supporters, Reid filed for the 1975 Las Vegas mayoral race. Still depressed from his senatorial loss, he ran a lackluster campaign, and voters rejected him in favor of Bill Briare.

In mid-1977, O’Callaghan appointed Reid to succeed Peter Echeverria as chairman of the Nevada Gaming Commission. It looked like a political plum, but proved to be a hot potato.

Sometime during the mid-1970s, members of the the Chicago and Kansas City mobs began buying into Las Vegas, filling the void created by the departure of Howard Hughes, and the retirement of old-line crime bosses such as Meyer Lansky.

The front man was Allen Glick, whose Argent Corp. purchased the Stardust and Fremont hotels. The enforcer was a deadly thug, Anthony “Tony the Ant” Spilotro. Mr. Inside, the guy who actually ran the Stardust, and skimmed millions in untaxed dollars for the Chicago and Kansas City bosses, was Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, a convicted sports fixer. Rosenthal posed variously as Glick’s assistant, entertainment director and food and beverage manager. In 1976, he was forced to apply for a state gaming license, but it was denied based on his criminal background.

Rosenthal and Glick decided to fight. On the public opinion front, the Las Vegas Sun and the Valley Times abruptly reversed earlier positions favoring strict gambling regulation, and began howling about the high-handed tactics of state gaming authorities in general, and the abuse of Rosenthal in particular. On the legal front, Rosenthal hired Oscar Goodman, who eventually took the case to the Nevada Supreme Court, which affirmed the state’s broad rights in granting privilege licenses. The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case.

Lefty’s last stand came in December 1978, when he came before Reid’s five-member Gaming Commission, which unanimously voted to deny Rosenthal’s application.

Rosenthal pitched an impressive tantrum. He accused Reid of having a complimentary lunch with Las Vegas Sun executive Brian Greenspun at the Stardust. Reid recalled the lunch, but pointed out that he wasn’t on the Gaming Commission at the time.

“Of all the jobs I’ve held, that was the most educational,” says Reid. “Before that, the words `organized crime’ were nothing but words. When I took over the Gaming Commission, they still didn’t mean anything. But that changed when they divulged all the FBI tapes, and we found hidden interests in the Aladdin and at all the Argent properties. They put bombs on my car, there were threatening phone calls at night, people tried to bribe me and went to jail.” (The car bombs were simple devices designed to light a spark in the gas tank. They failed to work.)

Wiseguy Joe Agosto, masquerading as “entertainment director” at the Tropicana, was heard on an FBI wiretap bragging to his bosses in Kansas City that “I’ve gotta Cleanface in my pocket,” which the feds believed to be a reference to Reid. A five-month investigation concluded that Agosto’s boast was nothing more than an attempt to show his superiors that he was “connected,” and vindicated Reid.

Gov. Robert List asked Reid to remain chairman, but he declined, and left office in April 1981.

By 1982, Nevada was awarded a new congressional seat representing Southern Nevada, and Reid beat Republican Peggy Cavnar to become the first to occupy it in 1983.

Almost immediately, Reid denounced the high-level nuclear waste repository proposed at Yucca Mountain.

Elected to the Senate in 1986, Reid concluded the long-unfinished task of creating Great Basin National Park, and new wilderness areas.

Part III: A City In Full