Harley Harmon

It was a matter of money, not honor, said Harley A. Harmon. And a man who took a life for that reason should breathe the cyanide gas in Nevada’s state prison. No life sentences, no long years at hard labor, no breaks.

Men and women oozed sweat in the undercooled Clark County Courthouse of September 1931 while Harmon and attorney Louis Cohen battled for the life of John Hall. Hall and his wife, Eva, and the victim, Jack O’Brien, were all newcomers. They were part of the flood of boomers and outlaws who washed over Las Vegas as construction began on Hoover Dam. O’Brien stole money from Hall; Hall claimed he also tried to assault Eva sexually. He confronted O’Brien as he tried to drive away, saying, “I want to talk to you about that money.”

O’Brien turned and tried to strike Hall, and Hall shot him.

“People we used to call friends are submerged beneath the new arrivals flocking into our fold,” Harmon told the jury. “We welcome these people into our arms and our hearts, and will work with them, and mingle with them; but let them leave their guns behind, we want no murderers here!”

The jurors deliberated late, slept on it, reconvened at 8 a.m., and a short time later announced a verdict. Foreman Frank Williams handed the verdict to Judge William Orr, who handed it to the clerk. She stood and her voice trembled as she read, “We the jury … find the defendant John Hall guilty of murder in the first degree and sentence him to death.”

The dapper district attorney had set the market price for murder. Rackets were a growth industry in 1931, and guns were tools of the trade, but Las Vegas would honor no trade discounts on human lives. Harmon and his assistant district attorney, Roger Foley, tried five murder cases that year. Four killers were sentenced to the gas chamber, and the fifth survived with a life sentence.

Summing up Harmon’s life years later, the Review-Journal wrote that he was “credited with stemming the rising tide of lawlessness which swept the area with the start of Boulder Dam construction.” Harmon was a self-taught country lawyer and first ran for office by stumping the county in a buckboard; his son, as a county commissioner, would build an airport for jet airliners.

Born in Kansas in 1882, Harmon was himself the son of a self-taught lawyer but ambled far from those footsteps. He was an assistant circulation manager for a Los Angeles newspaper, then a railroad fireman, then an engineer. He came to Las Vegas in 1905 as a crewman on the new San Pedro, Los Angeles, & Salt Lake Railroad, and was stationed here in 1908. In 1909, The Las Vegas Age carried a story under the headline “Frightful Explosion.”

“On Sunday morning last, at 5:15, a train of 31 cars of oranges with two engines ahead and one pushing, was coming up the hill from Kelso to Cima, engine No. 3670 in the lead. Without an instant’s warning the crown sheet of No. 3670 dropped — a roar and it was all over. Harley Harmon, engineer of the wrecked engine, and G.W. Hogue, fireman, had their first knowledge of the explosion when they regained consciousness about 40 feet from the track where they had been hurled from the cab. They were uninjured except for some slight burns from the escaping steam.”

(The crown sheet is part of the firebox under a steam boiler. This didn’t require explaining to the readers of 1908.)

Harmon found a telephone and notified his superiors. He related the damage but assured the brass that he and all hands had miraculously escaped alive.

The exact words of the boss have been lost to history, but can be paraphrased:

“You’re fired, Harmon!”

“The hell I am,” responded Harmon. “I quit 15 minutes ago.”

He was an engineer without engine, but had political talents. When a convention deadlocked over whether to split Lincoln County and create a new one, it was Harmon who realized the wheels of government sometimes needed the proper lubricants. He asked his wealthy friend, Ed Clark, to procure a case of Yellowstone whiskey, which Harmon applied at the sticking spots. The rest was history and hangovers.

Thus did Harmon land on his feet in July 1909 as clerk of newly created Clark County. When Las Vegas incorporated in 1911, Harmon got the city clerk’s job as well, at a salary of $25 a month. That September he married a city commissioner’s daughter, Leona McGovern.

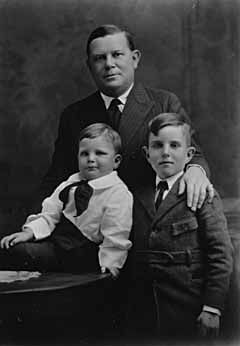

He was nearly 30 by then, but looked much younger. People started calling him, affectionately, “The County Kid.” Leona, shy but poised and beautiful, was nearly as popular as her husband. They had two sons; Charles, born in 1913, and Harley Emmett Harmon, born in 1918. Charles died of a ruptured appendix while still in his teens. The younger son would become well known as Harley E. Harmon, legislator, insurance agent, banker and pivotal player on the Clark County Commission.

In a September interview, Harley E. Harmon explained that his father’s duties as county clerk drew him into law.

“He used to love to go into the courtroom and watch the attorneys,” said Harley E. Meanwhile, he said, a former Stanford law professor, forced by tuberculosis to seek a desert climate “took a liking to my dad and thought he should study the law.” Studying in his spare time, he was admitted to the bar in 1919. Only two years later, he ran for district attorney and won the post.

Whatever happiness victory might have brought, however, was smothered in sorrow. Leona caught strep throat. Antibiotics hadn’t been invented yet, and she battled the illness a month before dying in October 1921 at the age of 29. Her boys would be left to the care of their widowed father and their grandparents, until the elder Harmon remarried in 1924, to Veronica Wengert. The second Mrs. Harmon lived to the age of 96.

One of Harley E.’s earliest memories is of seeing a burned-out Ku Klux Klan cross on Fremont Street He was not yet 4 years old in 1922, when his father launched an investigation of the local klavern. A membership list of the local organization turned up when Los Angeles police raided the Klan’s Pacific Domain headquarters.

District Attorney Harmon got the list and, apparently, let the locals know he had it. Craig F. Swallow, who gathered a history of Nevada’s Klans as a master’s thesis at UNLV, wrote, “Though the membership roster was not publicly disclosed, the loss of anonymity was a deterrent to Ku Klux Klan activity. The Las Vegas Klavern suspended activity and soon ceased to exist.”

Harmon’s duties didn’t require him to enforce Prohibition, as it was a federal law rather than a state one. He didn’t follow it, either.

Once he was traveling in the northern end of the state with C.P. “Pop” Squires, the prissy-looking publisher of The Las Vegas Age, and went into a hotel bar. “They had green rivers, sarsaparilla, and like that to drink,” related Harley E. “My father gave the password so they could go in back and have a real drink,” but the bartender ignored him. The D.A. asked why. “The bartender says, `That guy looks like a minister and we’re not going to let you in as long as you got that minister with you.’

“My father said, ‘He’s not a minister, he’s a son-of-a-bitching Republican!’ ” Harley A. Harmon was a yellow-dog Democrat and proud of it.

He ran twice for governor, but was unable to overcome favorite-son candidates from Northern Nevada, which then had most of the voters. He served four years on the Public Service Commission, became interested in the rapidly changing field of transportation law, and became attorney, lobbyist and organizer for the Nevada Trucking Asso- ciation.

In 1947, the old warrior was called to speak at a gathering of the Young Democrats in Reno. The Review-Journal reported, “As he warmed up to his subject, urging his listeners to carry forward the party banner in 1948, many seemed to sense here was an outstanding oratorical appeal. Old-timers nudged each other and whispered it was the best speech of a long career … As he reached the climax of his address, the speaker declared dramatically, ‘I’d give my last breath for the Democratic Party!’ ”

He sat down — and slumped to the floor with a fatal heart attack.

Meanwhile, Harley E. had learned the political ropes. When he decided to go to law school in Washington, D.C., Sen. Berkeley Bunker got him a job there operating the elevator in the Senate Office Building.

At the time, Harley E. disliked Nevada’s senior senator, Patrick McCarran. His father had helped McCarran get elected and had expected to be named U.S. attorney for Nevada, but McCarran appointed somebody else.

Harley E. took the only revenge he could.

“Anytime I opened the door and saw McCarran I would close it and go either down or up,” he said. “One Saturday morning … he put his foot in the door, and said, ‘Senate’s not in session today, drive this thing up to the top floor and shut it off because you and I are going to have a talk.’ ”

McCarran did most of the talking, explaining that his father’s letter requesting appointment had been intentionally sidetracked by a secretary who was friendly to another attorney who wanted, and got, the federal appointment. Eventually, McCarran become a mentor for the younger Harmon.

In World War II, Harley E. Harmon served in the U.S. Navy gun crews of merchant ships running military supplies through hostile waters. He lost interest in law school, returned to Las Vegas in 1946, and married Cleo Katsaros in 1947. Their sons, Harley L. and Jeff, would eventually take over the Harmon business interests.

In 1947, the younger Harmon served his first and only term in the Legislature. He started an insurance agency in Clark County, got elected to the Clark County Commission in 1950, and found that he who won a commission seat quickly became a successful insurance agent.

“I make no bones about it. Business came to you. For instance, I wrote the Dunes Hotel exclusively. I wrote the original Stardust. I’m not kidding myself. I was a county commissioner!”

But not having to worry about making money, in those tolerant times, gave commissioners leisure to address the pressing problems of their offices.

“We revamped the road department and started building roads, like Nellis Boulevard. At the time, all those enlisted men and officers from Nellis Air Force Base, in order to get into town, had to come through North Las Vegas and Las Vegas, and North Las Vegas was ticketing them.” A Nellis brass hat ran into Harmon at a Lions’ Club meeting in Henderson and asked him to build a road connecting Henderson, where many Air Force personnel lived, to the base. The road became an important artery, but its original purpose was to bypass a speed trap.

Harmon was instrumental in getting sewer service into Paradise Valley, which was a larger accomplishment than it sounds in retrospect, with long-term consequences.

“We had water in Paradise Valley but were at the beck and call of the city of Las Vegas as far as sewerage was concerned. C.D. Baker was mayor and wanted to annex. I said I had no objection to annexation, ‘But how long’s it gonna take you to get sewerage out to those hotels?’

“He said, ‘Well, we might get around to it in three or four, five years.’

“I said, ‘Well, that’s not right. You’re going to increase our taxes; you ought be able to do better than that.’

“One day I was sitting in my office and guy walked in and introduced himself. Said, ‘I hear that you wanta build an outhouse.’ ” Actually, Harmon said, the guy put it less delicately, but Harmon cleaned up the quote.

The caller was Walt Gibbs. “All I want is I’ll sell the bonds, and take my profit from the sale,” said Gibbs.

The county providing urban services removed any incentive Strip powers might have had to consent to city annexation. That froze the city limit at Sahara Avenue, where it remains to this day.

Harmon served 12 years on the commission. He helped build the airport that brings most tourists to Las Vegas.

Like his father before him, Harley E. was offered more than one chance to run for governor, but, unlike him, never ran.

He elected instead to concentrate on business, as one of the founders of Frontier Fidelity. Later, he put together a group of local investors to buy Nevada State Bank, and talked Parry Thomas, of Bank of Las Vegas, into financing the deal.

Under his leadership the bank grew from assets of $7 million in the early ’60s to some $105 million by the time he sold out in 1976. Its strength lay in being locally owned and therefore understanding local issues and opportunities.

How well Harmon’s financial institutions respected and understood their heritage was clear to anybody who got a bank statement. For a time, each statement envelope contained a one-page profile of some colorful character from Nevada’s history. The profiles reflected original research and writing by Elbert Edwards, an educator who would later publish the respected history book, “200 Years in Nevada.”

Harmon had been in Edwards’ seventh-grade class, and his most enduring lesson had been about concentrating on studies.

“Edwards was about six feet two and had fingers that were three times the width of an ordinary man’s. We were on the second floor, windows were open, and Vince Harrington and I were in the back. Mr. Edwards was explaining how the pyramids were built, in his opinion. It was boring so Vince and I were chatting back and forth. I noticed the room got really quiet, and suddenly I was yanked out of my seat and so was Vince.” He dangled both out the window and asked the class, “Should I drop ’em?”

“Yeah, drop ’em!” cried the boys’ classmates.

The brawny intellectual threatened to drop them a couple more times before returning the kids to their seats with orders to pay better attention.

Nearly 30 years later, Harmon learned that Edwards had retired, and called him up. “I got a chance to get even with you for holding me out the window,” he told Edwards. “How’d you like to do some historical research for us?”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full