George ‘Bud’ Albright

Nobody has to tell you when Comdex or the Consumer Electronics Show are in town. The traffic on and around the Strip is gridlocked. The sidewalks are packed with business suits and nary a fanny pack in sight. It’s a mess.

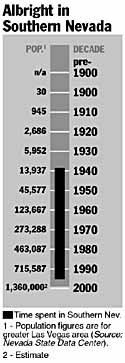

Blame it on Bud. He was George “Bud” Albright, the man who virtually built the Las Vegas Convention Center and conceived the self-perpetuating funding mechanism by which to expand and promote it.

But if you blame Bud for the commotion and disruption caused by more than 40 million visitors who attended 35,348 conventions at the facility since it opened in 1959, then credit him for the $35 billion they left in Las Vegas.

Albright was born in Pittsburgh on Dec. 6, 1909, to George and Bertha Mae Albright. By the time he was 10, his father had contracted tuberculosis, and the family moved to Albuquerque, N.M. His father died when Bud was 17, leaving the breadwinning duties to him and elder brother Jack. Bud had to leave high school in his early teens. At 18, he married Marjorie Hageman and they had one son, George LaVerne, who goes by “Vern” and is now a Las Vegas attorney. The couple divorced after three years.

In 1931, Albright struck out for Las Vegas, where he joined brother Jack in the typewriter and office machine business. Their staple client was the Six Companies building Hoover Dam, and business was brisk. The dust from the construction project took a heavy toll on office machines, and they had to be constantly cleaned and repaired. In fact, says Vern, after the Albright Brothers had trucked a load of machines from Las Vegas out the unpaved Boulder Highway, they were usually so clogged with dust that they had to be taken apart at the site and thoroughly cleaned.

In Las Vegas, he married Ellen Finnerty, and they had two more sons, Karl Thomas, a retired 20-year veteran of the Clark County Sheriff’s Department who now owns a carpet and floor covering business, and Kenneth Edward, a business management consultant.

The three sons gathered around a table to discuss their father are reverential. That is, until they start telling Dad stories.

“He once told us, ‘My boys, there is nothing your Pappy can’t do,’ ” says Karl. And it wasn’t an idle boast. Bud Albright could stitch up a badly injured dog one day and supervise construction of a great public building the next. He could rebuild a carburetor or perform a valve job on a 1951 Chevy, then fly off to Carson City and shepherd a pet bill through the Legislature. He learned by doing and by reading. In his final years, recalls Vern, his mortality worried him less than his failing eyesight.

“He was terrified that he would go blind and wouldn’t be able to read.”

Or build things. He was a hyperactive tinkerer who often would walk into the house after a full day’s work, and head directly for his shop. The boys remember the toys best.

There were the 9-foot kites that they could pull behind a pickup; the roller coaster on skate wheels that went from the second story balcony to the street. They also remember him as an incorrigible prankster. Sometimes, he would pluck a sleeping son from bed and lay him on the grass in the back yard. He would be watching through a window at sunrise, giggling, when the victim awoke. An avid hunter, he liked to lead large parties, and serve as camp cook. Someone would invariably cut into a pancake with a tin can lid buried inside.

In 1933, brother Jack Albright was commissioned by the Las Vegas Chamber of Commerce to build a model of the as-yet unfinished Hoover Dam. It would be displayed at the Los Angeles County Fair. Bud and younger brother Kenny were enlisted in the project, which took 57 days to complete. It was not precisely to scale and not accurate in details, but it wowed the fairgoers.

With the completion of Hoover Dam in 1935, Jack and Bud set out to build what Albright later would describe as “a romance in concrete and steel, a symphony in physical material.”

The second model of the dam took 2 1/2 years to complete, cost $25,000 to build, and cost the Albrights the life of their youngest brother, 17-year-old Kenny. It was hard for Bud Albright to talk about the tragedy, so none of his sons is certain exactly what happened that day.

It is known that a fire erupted in a bucket of gasoline in the shop. One version of the story has it that someone grabbed the flaming bucket, kicked the door open, and flung the flaming contents all over Kenny, who was just coming through the door. Another has that Kenny spilled the flaming liquid on himself as he tried to get the bucket outside. Consumed by flames, Kenny ran across the lot pursued by Jack and Bud, who tried to get him to the ground and roll out the flames. But he had been fatally burned.

As for the model, it was completed in time for the 1939 World’s Fair in San Francisco.

It has sidewalks, flagpoles and cars. It is rendered at 1 inch per 25 feet, and depicts 1 square mile. It is 18 feet long, 8 feet wide, 8 feet high and weighs 8,000 pounds. It uses 1,000 gallons of water to demonstrate the workings of the dam, tunnels, tubes, spillways. The topography of Black Canyon also is in perfect scale.

Today, it is in storage at the Las Vegas Convention Center.

In 1941, Albright joined the electrical firm of Luce and Goodfellow where, learning on the job, he became a master electrician, and wired the first Strip resort, El Rancho Vegas. In 1950, Albright formed Albright’s Courtesy Electric, an appliance and contracting firm.

By that time, Albright had been appointed to the Clark County Juvenile Advisory Board and was serving as chairman in 1946. The only juvenile detention facility was on Bonanza Road, a dirt-floored tin shack, with open holes for windows. It was totally unfit for human habitation. Albright launched a crusade to construct a decent juvenile home on Shadow Lane, near today’s Clark County Health Department.

Its first inmates were sons Karl and Kenny Albright. They had been playing “war” in an alley, and lit some garbage cans on fire to create the proper ambiance. Dad caught them in the act, marched them to the new juvie, and booked ’em.

In 1952, Albright was elected to the first of three terms on the Clark County Commission, and almost immediately saw the need for a convention center. He wasn’t especially concerned about increasing casino profits, since he regarded gambling as a foolish pastime, a sentiment he shared with one of his sons who had seen a slot machine and wanted to know what it was.

“Well,” explained Albright, “with this machine, you put $500 into it, and it gives you back $200.”

Albright’s interest in the convention center was based on the belief that relying solely on leisure travelers to support the city’s lifeblood industry made the city more vulnerable to economic downturns, and the perennial slow seasons.

Moreover, Albright understood that simply increasing the volume of visitors would result in a “multiplier” effect on nongaming businesses.

In 1955 the city and county formed a joint convention hall subcommittee, comprised of Horseshoe Club executive Joe W. Brown, Last Frontier founder William J. Moore and Bonanza Airlines President Edmund Converse. They eventually chose a piece of Brown’s land bordering Paradise Road.

In January 1957, Albright announced that construction would commence on the $4.5 million convention center. Albright worked out the financing formula himself. The answer was a room tax, collected each time an out-of-towner checked into a local hotel or motel. Kenny Albright remembers his father hunkered over his adding machine, trying to figure out how much revenue a room tax would produce at various rates. The numbers he produced were enormous.

“He thought he had put the decimal in the wrong place,” says Kenny. “He called Mom in and said, ‘Do this with me; I must be doing something wrong.’ ” He wasn’t.

Still, the attitude of the hotels was that collecting room taxes would be a nuisance. They had plenty of business, most of it weekend and summer leisure travelers, not conventioneers.

“And that was the selling point,” says Karl Albright, “He said, ‘We’ll bring conventions here not just in the summer, but also in the winter.’ ”

As chairman of the Clark County Fair and Recreation Board, the project was Bud’s baby, and in his characteristic hands-on approach, he spent as much time at the construction site as many of the workers. He drove contractors crazy, carefully scrutinizing the placement of practically every beam, poking batches of concrete to make sure they were mixed properly and always offering suggestions about how something could be done better or faster.

The Las Vegas Convention Center was completed in early 1959, and the city’s first big convention, The World Congress of Flight, was booked for April. Congress organizers were worried, because as the date drew closer, there still was no one in charge of running the center.

Albright was drafted, sold his business, resigned his seat on the county commission and was named executive director at a then-generous salary of $25,000 per year.

Those who had supported the convention center expected that the grand new building would be soon bursting at the seams with conventioneers every single day. That would happen eventually, but in those early days, Albright took a lot of heat for the lulls between conventions. Herman “Hank” Greenspun, publisher of the Las Vegas Sun, was particularly vocal in his denunciations of Albright’s management.

“He said one time that he thought he and Greenspun had buried the hatchet,” recalls Kenny Albright. “Until he opened the paper the next morning and found out where he had buried it.”

However, in the late 1960s, he was named “Convention Man of the Year,” by the local chapter of the National Hotel Convention Sales Managers’ Association.

In July 1967, he was fired in a secret meeting by the five-member Convention and Visitors Authority, chaired by Mayor Oran Gragson. Gragson told reporters Albright’s actions “contributed to the community’s lack of confidence in the operation of the convention authority in the past few years.”

Albright’s sons agree that the main reason for the firing was Greenspun’s interminable broadsides against their dad, but Karl allows that his plain-spoken manner may have chafed some of the powers that were.

“Dad was not famous for being tactful,” he says.

Actually, the reason may have been money. In 1967, Albright was being paid $29,500 per year. Gragson made a point of informing reporters that the salary of his replacement, Radford Cox, “will not exceed $17,500.”

Less than a year later, Albright was hired by Clark County with the title of director of special projects. The room tax he had created helped him fund parks, swimming pools and recreational facilities. He was also placed in charge of acquiring land for the ongoing expansion of McCarran International Airport.

In 1973, Ellen Albright died, and the following year, he took his third wife, Flora Grant. In 1979, at age 69, Albright retired, but stayed active in the Masonic Lodge and the Kiwanis Club, where he was a 50-year member, and the Clark County Sheriff’s Mounted Posse.

“We had lunch with him once a week for 35 years, except when one of us was out of town,” says Vern.

By the time he died in 1996, he was generally acknowledged as “The Father of the Convention Center.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full