Superintendent search spurs salary debate

Is a salary of $270,000 enough?

Clark County School Board President Carolyn Edwards posed the question last week when short-time Superintendent Dwight Jones announced his resignation, and it surely will be a point of discussion today as the district begins planning the search for his replacement.

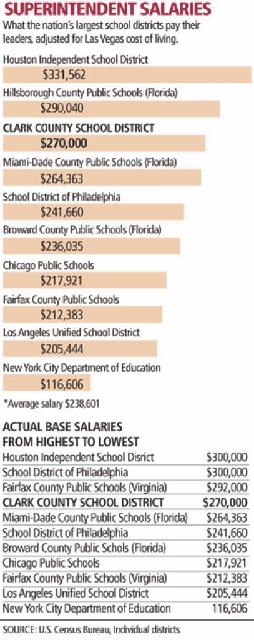

Jones, who didn’t cite salary as a reason for his departure, already receives $20,000 more than his counterpart at the much larger Chicago Public Schools, which has a third more students than Clark County.

And he receives $57,000 more than the head of the New York City Department of Education, the nation’s largest district with more than 1 million students, three times that of Clark County.

Paying the superintendent more is “not popular in this community,” Edwards conceded during a news conference March 6 at which Jones formally announced his resignation after two years at the helm. But, she pointed out, “whoever comes in is going to be the superintendent of the fifth-largest school district in the nation.”

Jones’ base salary of $270,000 lands right on what’s average for the country’s top 10 districts, and it’s just 10 percent off the high of $300,000 in Houston and Philadelphia. In fact, Jones’ pay is actually high when taking into account the lower cost of living in Las Vegas compared with other communities with large districts, which are mostly in expensive urban areas, such as Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City and Arlington, Va., according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

IS MONEY THE ANSWER?

Edwards’ initial reaction to launching a superintendent search was suggesting a salary increase to attract qualified candidates. But board members Erin Cranor and Linda Young are adamant that more money isn’t the answer when the current salary is already competitive.

“I’m not for waiting for Superman,” Young said in an interview Wednesday. “And if you’re concerned about the cash, that won’t work.”

Young pointed to previous superintendents who refused bonuses and requested pay cuts for the sake of the cash-strapped district.

Today, the Clark County School Board will discuss whether to search locally or nationally for a new superintendent, which will determine where they set the salary, board member Lorraine Alderman said.

“We have to cross that bridge first,” she said.

The board meets twice to discuss the search, once at 9 a.m. and again at 4 p.m., according to its agendas. The meetings take place at the Greer Education Center, 2832 E. Flamingo Road.

In October 2010, the School Board hired then-Colorado Education Commissioner Jones after a national search for a compensation package totaling $358,000.

Jones resigned halfway through his four-year contract and said he needs to care for his ailing mother in Texas. He gave just two weeks notice although his contract calls for 90 days.

He is leaving with the highest salary of any departing superintendent in Clark County’s history.

“I don’t know that the salary needs to be increased,” Edwards said Wednesday, softening her original stance.

PERKS OF LEADERSHIP

On top of salary, urban superintendents are often given substantial benefits packages averaging $141,000 in value, according to a survey of 56 urban superintendents done by the Council of the Great City Schools, an organization of the nation’s largest urban districts.

Jones’ benefits amount to about $88,000, including a $700 monthly car allowance and $660 a month to offset costs of participating in community events.

Benefits are what board members Young, Edwards and others thought the district could improve for a future superintendent.

It is becoming more common for districts to give bonuses for improving performance, such as raising the graduation rate or the percentage of students that pass state tests. If the bar isn’t reached, no bonus.

About 40 percent of urban districts provide such incentives, awarding superintendents between $5,000 to $65,000 for reaching certain student-performance benchmarks, according to the council.

Clark County no longer offers that.

Previously, the district offered Superintendent Carlos Garcia a maximum 6 percent bonus every year if he could show gains in student performance. He held the position from 2000 to 2005 and once earned a $10,000 bonus because of improved student performance, which he declined because of the district’s financial hardship.

Although undecided on the superintendent’s salary, School Board member Deanna Wright said she is open to bringing back performance pay.

“Maybe it’s time we make that leap,” she said.

But if the superintendent is awarded for student gains, teachers should be too, Young asserted.

“Rank-and-file teachers are going to make that happen,” said Young, irritated about the push to make the superintendent’s salary “competitive” while she said teachers are underpaid.

Nationally, the average teacher salary is $54,200, but the average Nevada teacher earns under $50,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

A few urban districts are experimenting with teacher bonuses for student performance, but not in Nevada, although it’s being discussed.

If the district chooses to simply increase salary to win over the next superintendent, that would make a “dangerous statement,” Young said.

“I don’t want to buy anyone,” she said, noting that someone like that “can’t be a committed, caring superintendent” because their priorities are skewed.

A devoted superintendent will forgo making personal gains at the expense of students, Young said.

Jones’ predecessor, Walt Ruffles, requested a 10 percent pay cut in 2009 and another 10 percent pay cut in 2010 because of the tight budget. That decreased his salary by $61,400. He was hired in 2006 for $290,000 but retired in 2009 making $246,000.

Before Rulffes was Garcia, who resigned in 2005 with a $212,000 salary. Brian Cram, who retired in 2000, earned $158,000 for the last year of his contract.

SUPPORTING EDUCATION

Jones was awarded a salary higher than his predecessors and was allowed some nontraditional perks.

In addition to a $15,000 relocation payment, Jones was given free housing for his first six months in the district. The Public Education Foundation, a local education nonprofit that employed Jones’ wife during his tenure, raised $22,540 for the housing subsidy.

Board member Erin Cranor argued that Clark County didn’t lose Jones because of shortcomings in his compensation package.

Cranor said that a community that makes education and reform priorities are what keeps a superintendent, not a larger pay check and extra perks.

“The system has got to be geared toward supporting the student.”

And that support isn’t fully realized in Nevada, although the tides are changing. In Carson City, legislators normally in opposition are showing bipartisan support for improving schools this session, she said.

“I don’t think compensation is the issue here,” Cranor said.

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.