Schools helping students become bilingual, biliterate

At Harmon Elementary School, 14 first-graders settle on the rug for their Tuesday morning vocabulary and spelling lesson.

Cristina Rodriguez-Nguyen, their teacher, chooses one student at a time to spell vocabulary words using cardboard letters arranged in plastic slots at the front of the room.

"Dormir, dor-mir," she says to one boy, slowly pronouncing the Spanish word for "sleep."

The boy arranges the letters correctly, and Rodriguez-Nguyen prompts the other students to offer a round of "aplauso" for his efforts.

Just up the hall, a similar scene is unfolding in Josephine Holland’s first-grade classroom, except in English. When a girl correctly spells "boot," Holland tells the other students to "give her a hand."

Halfway through the day, the students switch classrooms and receive instruction in the other language.

Harmon is one of the Clark County School District’s eight dual-language schools, designed to help students become bilingual and biliterate, able to speak, read and write in both English and Spanish.

Administrators say Clark County has comparatively few such schools for a district its size and may lose them if budgets continue shrinking. This leaves students less able to eventually compete in a global economy, said Miriam Benitez, dual-language coordinator for the district’s English Language Learner program.

Dual-language programs "are our attempt to make our kids as competitive as possible," she said.

THE BENEFITS

In addition to learning a second language, students who attend dual-language schools score as well or better on standardized math and English tests as those who don’t, according to a broad spectrum of education research.

But many of the benefits of such programs don’t necessarily translate into test scores, said Eugene Garcia, vice president for education partnerships at Arizona State University. Garcia has written extensively about language teaching and bilingual development.

"Not only are there linguistic benefits, there are cognitive benefits," he said. Dual-language students, for instance, seem better able to focus in school.

"If you’re learning two languages you have to pay attention more than when you’re learning one," Garcia said. And people who are bilingual appear to "get a three- to five-year reprieve on memory loss" later in life.

Children who are exposed to "whatever language" learn it, he said. "If they are exposed to more than one language they learn it as well, without any negative" outcomes.

Garcia said research also shows that students who attend dual-language schools develop more positive attitudes about students from other cultural backgrounds and are more comfortable interacting with people from other ethnic groups.

"It’s a win-win," Benitez said. "The students are bringing cultural sensitivity and awareness into each others’ lives. It’s a beautiful thing."

Students for whom English isn’t the primary language do especially well in dual-language schools.

"The one program that seems to close the achievement gap (for English Language Learners) is a dual-language program," Benitez said.

That’s because ELL students at such schools "learn content in their native language as well as learning English," she said. "They’re not lacking anything."

The district has identified 92,000 of its roughly 310,000 students as English Language Learners. Spanish is the primary language for the majority, about 85 percent of such students.

HOW THE SCHOOLS WORK

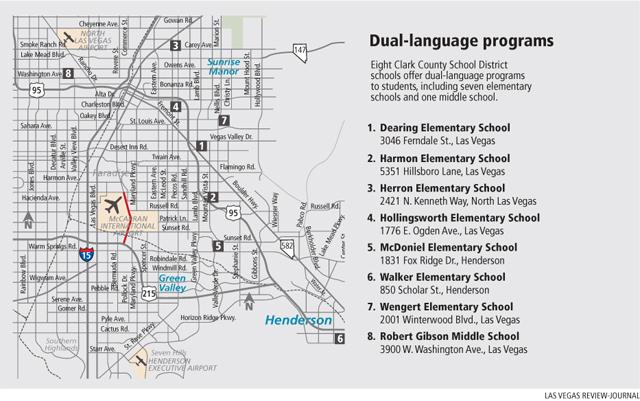

The district’s dual-language schools include seven elementaries — Dearing, Harmon, Herron, Hollingsworth, McDoniel, Walker and Wengert — and Robert Gibson Middle School.

Only McDoniel and Walker offer schoolwide dual-language programs, Benitez said. The other schools have a limited number of dual-language classrooms.

The district’s goal for the programs is to offer half a student’s curriculum in English, half in Spanish. Students are shared between two teachers, one who delivers instruction in each language.

Lessons aren’t translated when switching from one language to another. Instead, students learn language through parallel content.

Ideally, the mix of students in such programs would also be half and half, with an equal number of students whose primary language is Spanish or English.

"The goal is to bring together kids who may not speak English with kids who do, with a goal of generating kids who can speak both languages," Garcia said.

But it doesn’t always work that way in Clark County because of the demographics of the communities in which the schools are located. English is the primary language for a majority of students at McDoniel and Walker, Benitez said. At Herron, the primary language for most students is Spanish.

Dual-language programs at such schools become "one-way," Benitez said.

About 1,000 dual-language schools are in operation nationwide, Garcia said.

"While they are predominantly Spanish-English, they come in various languages," he said. "French, Chinese, Navajo, Tagalog."

Dual-language schools originated decades ago in cities such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York and Chicago when middle-class parents showed an interest, Garcia said.

"They saw that this is becoming a global competitive environment and that adding a second language early on might be beneficial to their kids," he said.

Educators soon realized that such programs provided ELL students the same opportunities as more economically privileged classmates, he said.

PROGRAMS FACE CHALLENGES

The school district should be able to maintain its dual-language programs even with potential budget cuts this year, Benitez said.

But that will become more difficult if there are more cuts in the future. And it will be even harder to grow the number of such programs, she said.

"We’re just trying to keep intact the ones that we have, to protect them," she said.

To offer a dual-language program, a school must recruit bilingual teachers. With budget cuts, some of those teachers could be "bumped," jeopardizing a school’s program.

"If that was your fourth-grade, Spanish-speaking teacher, your fourth-grade program is done," Benitez said.

While bilingual teachers at dual-language schools aren’t paid more in Clark County, they usually have to assume more responsibility than other teachers, she said.

"It is more work because you have to work with a partner," she said. "Sometimes materials aren’t available in Spanish, and the Spanish teacher has to translate or create her own materials."

Some bilingual teachers aren’t willing to sign on for that.

Building dual-language schools takes time and commitment, Garcia said.

"You can’t just say, ‘Tomorrow we’re going to have these programs in Las Vegas.’ "

Parents also must "buy in" to the program, Benitez said.

"Kids will come home with Spanish homework. It is a commitment."

Most parents realize the benefit of having their children learn a second language, she said. But some resent it.

"They say, ‘Why do my kids have to learn Spanish? This is America,’ " Benitez said. "I say, ‘We want our children to be able to compete globally.’ Other countries are teaching their kids three or four languages. Why should our kids only have the option of learning one?"

Unless the dual-language program is schoolwide, parents can opt their children out of it. If the program is school-wide, parents can get zone variances to send their kids elsewhere, Benitez said.

Parents also can request zone variances so their children can attend dual-language schools, but space is limited.

"You don’t want your classes bursting at the seams," Benitez said.

That may become a problem anyway at schools such as Harmon, which is losing several teaching positions next year because of budget cuts.

"The (dual-language) program may look different," said Principal Henry Rodda. "There will be less one-on-one help" and bigger class sizes.

Further cuts could threaten the program’s future, he said.

That would be a bummer for the first-graders at Harmon, who seemed to really enjoy Rodriguez-Nguyen’s Tuesday vocabulary lesson.

She directed them to spell each of the words "en el aire, en la mente, en el piso" — in the air, in the mind, on the floor.

The students helped each other in English and in Spanish.

As he used his index finger to spell a word in Spanish in the air above his head, one boy exclaimed: "This is fun!"

Contact reporter Lynnette Curtis at lcurtis@reviewjournal.com.