PAHRUMP —The land on West Irene Street near Warren Street is typical desert real estate, dotted with brush and delineated by gravel roads. Litter clings to the hardpan, and a tire rim lies on the side of the road.

The parcel isn’t much to look at, but its history is rich. This land, along with millions of other acres across the state of Nevada, was granted by Congress to generate revenue for the state’s public education system.

But through a series of trades with the federal government, a desire to lure settlers and some shady dealings by state officials, much of that rich educational dowry — commonly known as school trust or school grant lands — is now gone.

Only 2,914 acres remain from the original nearly 4 million, generating mere dimes compared with the revenue earned by such land in other Western states.

A small group of advocates hopes to change that by campaigning for Congress to restore Nevada’s trust lands.

“Maybe, you know, things could’ve been a little bit different if there was an alternative strategy of not just disposing (land) to settle this state,” said Charlie Donohue, administrator of the Nevada Division of State Lands.

The school trust lands date to the Silver State’s founding in 1864, when the federal government set aside a pair of 2-square-mile sections of land in every 36-square-mile township to benefit public education. Dozens of states received similar deals upon statehood, though a few Western states received four sections per township.

Revenue from the sale or lease of that land in Nevada was to go to the state’s Permanent School Fund. The interest earned from that fund remains one of multiple sources of education funding today.

Yet over the next century, Nevada made a trade with the federal government for far fewer acres and ultimately sold off the majority of the land to the state’s early citizens. These parcels and others types of federal land grants today lie beneath the Bellagio on the Las Vegas Strip, the beautiful Secret Cove on the shores of Lake Tahoe and even parts of Lake Mead — granted long before it was even a lake.

The school trust lands and the revenue they generated also were subject to abuses, including embezzlement by the first state treasurer and a land scandal that rocked the Nevada Legislature in the 1950s.

Today, Nevada’s remaining school trust lands generate less than $5,000 per year for the school fund — versus the nearly $67 million Colorado’s school trust lands pumped into its education fund in fiscal 2019 or the $1.3 million Idaho trust lands earned the same year.

Now advocates are asking Congress for another 2 million acres to match the deal that other dry Western states received upon being admitted to the union. They say giving Nevada more acres would make a huge difference in a state eternally scrambling for education funding.

“Who doesn’t want to help their own kids? Who wouldn’t want to help their neighbor’s kids?” said Paul Johnson, chief financial officer of the White Pine County School District and one of the advocates. “To me, it is just a way to generate goodwill in Nevada and help students regardless of background and origin.”

Land and corruption in the Battle Born state

When Nevada joined the union during the Civil War, it received the 16th and 36th parcel of every township for education.

The parcels were distributed evenly throughout the new state — but that was a problem. Many of the parcels were in dry, uninhabitable areas, while others were on top of mountains.

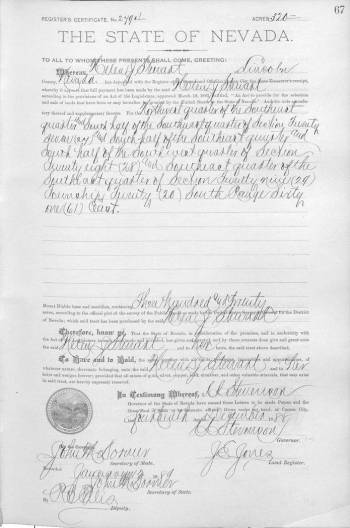

The random distribution of the parcels led Nevada to propose an exchange in which it would return the 4 million acres to the federal government for 2 million acres — the location of which the state could select. Congress accepted the deal in 1880, and the state soon began selling the prime parcels of land to settlers through the state surveyor general’s office. The parcels originally went for $1.25 per acre, to be paid off over time. The money from those sales presumably went into the Permanent School Fund to generate interest.

The swap spurred land sales, particularly near habitable areas closest to water. Over the next 100 years or so, nearly the entire Las Vegas Valley, Pahrump and the areas around Reno and Carson City fell into private ownership — through the sale of school trust lands or roughly 700,000 other acres granted by the federal government.

At the time, land experts argue, the deal made sense for a remote state with a small population. But whether the trade was good for Nevada in the long run is another question.

“The question comes up: Was it a good deal?” said Robert Stewart, a land historian and former national chief of public affairs for the Bureau of Land Management. “They thought it was. We can’t go back now.”

State’s abuse and mistakes

Nevada experienced trouble with the school trust lands from the start.

The state’s first treasurer, Ebenezer Rhoades, embezzled $62,226 from the school fund — but that wasn’t discovered until after his death in 1869, according to a 1980s analysis by former state Treasurer Patty Cafferata and former state Superintendent of Public Instruction Dale Erquiaga.

That theft robbed Nevada schools of nearly $300 million in compound interest that would have accrued over more than a century, Cafferata estimated.

In the 20th century, there was more political maneuvering as Nevada politicians concluded that they got a raw deal.

“In actual fact, the 2 million-acre trade was a bad bargain,” Gov. James Scrugham said in his 1925 State of the State speech.

On top of that, the purchasers of roughly 30,000 acres had stopped making payments on their parcels — land that Scrugham deemed “practically worthless.”

The Legislature acted quickly, drafting bills to exchange the land with the federal government yet again — this time for different parcels for state parks and other purposes.

Nevada Attorney General Michael Diskin ruled the bills were illegal, because the revenue from that land was only to be used for educational purposes as outlined in the state’s Constitution.

But when Congress granted the exchange a year later, the state took school trust land for itself anyway.

Today that land includes parts of 13 state parks and other state buildings — including 8,725 acres of Valley of Fire State Park, 1,578 acres of Cathedral Gorge State Park and 80 acres of a state prison in Carson City.

It’s unclear whether the Legislature created those parks and other government properties knowing the action had been deemed unconstitutional.

Workers in the state lands office rediscovered the diversion in the 1980s. Pamela Wilcox, administrator of the Division of State Lands at the time, fought for reimbursement for the Permanent School Fund.

“I initially went to the budget office and tried to get (the land) appraised for current market value, and as usual the state was broke,” she said. “They said, ‘Oh, can’t we do it a cheaper way? Can’t we do it for the value at the time that this happened?’ ”

The state ultimately reimbursed the education fund in two installments. One 1987 payment covered seven parcels based on the value of the land at the time of its diversion. The state paid a total of $250 for 200 acres of Kershaw Ryan State Park and $1,973 for nearly all of the 1,784-acre Cathedral Gorge, according to a 2006 analysis of Nevada’s school trust lands written by Christopher Walker, now a professor at Ohio State University.

Another reimbursement in fiscal 2005 also valued the land at the prevailing price in the year the state took it over, with the exception of two buildings that were reimbursed based on market value. A working group that determined the reimbursement amounts added another $751,035 to the roughly $3 million payment, as some parcels had developed capital improvement projects on them.

Margaret Bird, a champion of school trust lands who led reforms in Utah and has assisted local advocates on the matter, argues that the fund lost out on years of leasing revenue. That also means the school fund lost out on decades of additional interest.

But a working group that calculated the 2005 payments concluded that the school fund was made whole, said Jim Lawrence, deputy director of the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources and a former Division of State Lands administrator, who served on the group.

That’s because the state’s general fund always covered any shortfall in education spending that other state resources, including the Permanent School Fund, could not meet.

“Our goal was to bring the Permanent School Fund to the level it would have been at had we done the compensation at the time,” Lawrence said.

Legislature’s misdeeds

The lack of oversight of Nevada’s school trust lands bubbled into scandal in 1955, when a grand jury report in what was then Ormsby County concluded that a number of legislators and state officials used their positions to acquire desirable state lands granted by the federal government, including school trust lands.

Government employees were aided by the state’s surveyor general, Louis Ferrari, who tipped them off whenever land was available, the grand jury said.

But the report also cast blame on the Legislature, noting that it had “palpably failed to investigate acquisition and disposition of state lands.”

Land transactions “have become tempting and profitable enterprises especially for those persons involved in or close to governmental positions,” the grand jury concluded.

The report led to the elimination of the surveyor general’s office and the creation of the Division of State Lands, according to Walker.

In other states

While Nevada was selling off its school trust lands, other Western states were slowly amassing revenue from theirs, generating funding for schools that in some cases today is nearly 20 times what Nevada distributes.

States vary in how they manage their lands and invest their funds. In general, they sell or lease the lands and send the revenue to a fund that’s equivalent to Nevada’s Permanent School Fund. The earnings generated off the investments of that fund are given to public education.

In Utah, the School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration manages 3.3 million acres of remaining school trust lands, plus nearly 1 million acres of mineral-only lands. The agency generates revenue through a number of avenues, including energy and mineral royalties.

In Colorado, which has largely stopped selling trust lands, the Colorado State Land Board offers leases on its remaining 2.8 million acres.

In Nevada, most Permanent School Fund revenue comes from other sources, including fines from justice and district courts.

But advocates argue that those poor returns are not entirely Nevada’s fault, noting that other states received more land than the Silver State, even though much of Nevada’s arid landscape cannot be developed.

Arizona, New Mexico and Utah — admitted to the union after Nevada — each received four 2-square-mile parcels of each township for education, or double what that Nevada got.

Nevada’s public education system also receives money from the federal government from other sources. The Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act, for example, earmarks 5 percent of sales of Bureau of Land Management land to the state’s school fund. It has generated $182.9 million since 1998. Counties also receive a payment in lieu of taxes for the land in their jurisdiction that is federally owned; in fiscal 2019, that totaled $27.3 million across the state.

Bird, whose reform efforts in Utah led to the creation of the state’s trust land administration, attributes Nevada’s losses in part to the limited knowledge of desert lands at the time.

“You entered the nation during the Civil War — Battle Born — and when you did so people didn’t know a lot about how arid Nevada was,” she said.

The push for more land

The land on the hillside off Timberline Drive offers a gorgeous view of Nevada’s quaint capital, which merged with Ormsby County in 1969 to create the Consolidated Municipality of Carson City.

The 313-acre parcel brings in the most money out of the state’s remaining 2,914 acres of school trust lands, which generated only $4,525 in total in fiscal 2019. Though it could be prime real estate one day, the parcel currently generates money through easements granted to Carson City and AT&T.

But local land advocates hope to change that picture. Their goal is to persuade Congress to retroactively grant the additional two parcels per township that other arid states like Arizona and Utah received at statehood.

While they’re honest about facing Nevada’s ugly past of mismanagement and malfeasance, they argue that the state did not receive a fair deal.

Nevada is also the state with the most federally owned land. In 2015, roughly 80 percent of the state was controlled by one of five federal agencies, according to a 2017 Congressional Research Service report.

— Click here to explore lands that the state selected to exchange with the federal government in 1880 and sell to private owners. Toggle the timeline at the bottom to populate the map.

— Click here to explore Nevada’s remaining school trust lands.

“There’s some room to move there, I feel … to give us an opportunity to infuse some more money into our kids,” said Lori Hunt, a former White Pine County School Board trustee and president of the national Advocates for School Trust Lands group.

But some land experts note that Nevada ultimately got from Congress what it asked for.

And even if the state gets an extra million acres, land historian Robert Stewart asks, who is going to buy or use it?

“The raw land of Nevada is raw for a reason,” he said.

Only two members of Nevada’s congressional delegation, Reps. Mark Amodei and Susie Lee, responded to requests for comment on the move to garner more school trust lands from the feds.

Lee’s office said in a statement that the first-term Democrat is glad Nevadans are looking for alternatives to address the state’s funding shortfalls.

Amodei said he’s open to the discussion of receiving more trust lands.

“I think if you’re going to have a discussion, it ought to be a global one,” Amodei said. “Here’s how much we think we can generate for you out of that, whether it’s another section (of land) or another acre per section or whether it’s a bigger chunk of SNPLMA money.”

Meanwhile, the amount of Nevada’s remaining school trust lands won’t change unless an act of Congress puts more acres back on the map.

“It’s a new day now,” said Bird, who noted that other states also have a troubled history with their school trust lands. “You can change the story going forward from here. You can’t change what’s happened to this point.”