Officials: Number of schools that met No Child Left Behind standards declined this year

Nearly two-thirds of Clark County schools failed to make the grade under No Child Left Behind in the 2010-11 academic year, officials announced Wednesday.

The low results garnered a flat reaction from Clark County School District leaders, who were not surprised by schools’ flagging performance under the federal education reform they view as flawed and expect to be short-lived.

"We see it, frankly, as a measure being used for just a couple more years," Deputy Superintendent Pedro Martinez said.

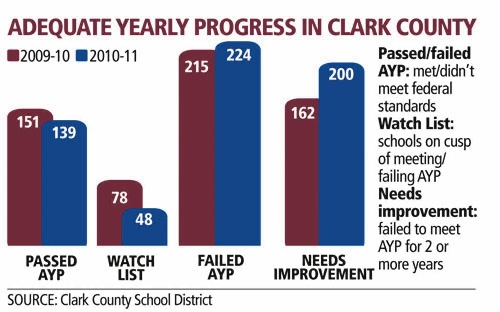

An increasing number of district schools are falling short of federal goals. Only 139 of 363 schools showed adequate progress this year, down from 151 in 2009-10.

In 2008-09, 190 schools met or exceeded the federal bar, which has been raised every year, making catch-up even harder. For example, only one-third of elementary students needed to be proficient in math for a school to meet No Child Left Behind requirements in its first year, 2002-03. But requirements have gradually been increased, with the program calling for 100 percent of students in schools nationwide to demonstrate proficiency in math, reading and English by 2013-14.

No school can achieve that, said Martinez, reiterating an often-made criticism about No Child Left Behind. Schools across the country are on the same downward trend as they approach the 100 percent requirement, which is an unreachable goal, asserted Martinez and several School Board members.

The system is "flawed," Superintendent Dwight Jones said, and for more reasons than just the goal of 100 percent proficiency. The problem is the method used to decide what adequate is.

For example, the district as a whole showed adequate progress in 2009-10 despite having 58 percent of its schools fail. That is because a district passes if a majority of either elementary, middle or high schools pass. Only high schools made the cut in 2009-10.

For a school itself to earn a passing status — called Adequate Yearly Progress — a certain percentage of its students must score as proficient and meet attendance or graduation requirements. But it’s not that simple. Test scores are broken down into 45 subgroups such as ethnicity and those with limited English skills.

If just one of those subgroups doesn’t make the grade, the entire school fails for the year. That happened to 30 district schools this year.

"For some of the schools, it has been devastating when they’re bumped because of one factor," School Board member Linda Young said.

For eight years, that has been the case for Cunningham Elementary School, east of Nellis Boulevard and south of Flamingo Road.

"We’ve had our hearts broken a couple times," said Principal Stacey Scott-Cherry, whose school has been vigilant in trying to make adequate yearly progress. "It’s all or nothing. Doesn’t seem fair."

This year, Cunningham finally cleared the bar for the first time "because of a lot of hard work," she said.

One of the biggest contributing factors was reducing teacher transiency and retaining 90 percent of school staff, she said. That was the foundation for improvement.

Next came additional federal funding for two years because they were labeled Title 1, meaning about half of the students were living in poverty, as determined by the percentage of children receiving free or reduced lunches.

The school hired math and writing strategists to better train teachers and work with small student groups. Teachers were paid to stay after school. Parents met with teachers multiple times a year to discuss student progress and how to prepare for standardized tests. And each student was given a "tracking folder" to chart individual progress.

"AYP is very important," Scott-Cherry said. "Teachers and administrators take it very seriously. "But our biggest goal is that we’re doing right by our students and showing progress, growth."

Growth is where the district wants the focus to shift.

"We don’t want to send the message that No Child Left Behind doesn’t matter," said Martinez, "but the growth model is the wave of the future."

Clark County school officials revealed a new rating system Wednesday, which is being developed for 2012-13. It would measure students’ growth over time instead of relying on an annual test to assess student proficiency in a given subject at just one point in time, which is what No Child Left Behind does. The district would be joining others across 18 states in placing less emphasis on No Child Left Behind.

"There’s a lot of backlash with No Child Left Behind," said Kenneth Turner, the special assistant to the superintendent who presented the preliminary growth model Wednesday to the School Board.

The new rating system would be more relatable to students and their parents and easier to understand than No Child Left Behind, Martinez added.

"I think we’re definitely moving in the right direction," Young said.

Using the growth model wouldn’t affect federal funding, said Jeff Halsell, district coordinator for No Child Left Behind. The growth model wouldn’t make the federal program irrelevant. The district has overhauled staffing at seven struggling Clark County schools in the past two years to improve student performance and meet federal goals. Five of these happened last year when three principals were forced out and all five schools had to replace half of their staffs.

Whether that continues to occur will be decided locally in the spring. No Child Left Behind outlines repercussions for schools that continue to fail, but the federal hammer has been slow to fall.

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@review journal.com or 702-383-0279.

List of schools and their standing in the No Child Left Behind program