Nevada State College faces grim future

Lesley Di Mare hovers in the back of the room.

"When do we start?" her assistant whispers over the clank of breakfast.

DiMare smiles: "Whenever they tell me. I’m just a little wind-up doll."

It is 8 a.m. on a chilly April morning and Di Mare is playing saleswoman in a downtown Las Vegas Mexican restaurant. About 20 people show up to hear her speech, sponsored by Hispanics in Politics. It’s one of many similar events she attends, selling Nevada State College.

Extolling the college has become her No. 1 job lately in this era of budget cuts.

Di Mare, NSC’s president, has statistics and logic and pie charts and emotion on her side. They’re all in her half-hour PowerPoint presentation.

The college is vital, she declares, a second tier in a three-tier system: community colleges, the state college, the universities. Each serves its own purpose. NSC originally focused on producing teachers and nurses, but it has expanded. Those are still its dominant programs — along with business, psychology and biology — but it now offers 19 different bachelor’s degrees.

NSC’s student body is 41 percent minority, 60 percent female, half first-generation college students. It is doing, Di Mare says, what it was built to do. It is producing graduates — 1,183 in its short history so far — in a state with one of the lowest percentage of college graduates in the country.

It serves students who might not otherwise go to college at all. Maybe their high school grades weren’t good enough, or they just don’t see themselves as university material. NSC requires only a 2.0 grade-point average for admission; the universities require a 3.0.

"We believe they still deserve places to go to school to get a four-year degree," Di Mare says.

She is preaching to the choir this day, to a group mostly sympathetic to her point of view. The goal, of course, is to get them to lobby legislators.

Because that’s who controls the purse strings.

CUTS ARE COMING

The college might be killed outright, or folded into one of the state’s other institutions, as lawmakers try to figure out how to run the government with less money coming in than is scheduled to go out.

Higher education is a huge target.

The higher education system — four community colleges, the state college, two universities and a research institute — accounts for about 15 percent of all state general fund spending in Nevada. It’s a big chunk of the pie.

Gov. Brian Sandoval has proposed cutting the higher education budget by $92 million next year and $162 million the year after that when compared to this year. (This year’s higher education budget is $558 million.) He opposes any tax increase, so cuts might be the only way to go.

Reacting to forecasts of more revenue for the state than previously expected, he last week proposed reducing those cuts to the higher education system by $20 million over the two years.

Higher education leaders say that is not enough. They say another $60 million in funding is necessary.

Democrats also presented an alternative plan last week. They proposed cuts less than half the size of Sandoval’s.

As legislators debate the proposals, the colleges and universities are preparing for the worst.

Higher education leaders are already factoring in a systemwide 5 percent pay cut, which replaces mandatory furloughs that save about 4.6 percent already. Also expected are tuition and fee increases of somewhere around 13 percent in each of the next two years to help make up for the reduced state funds. The additional salary reductions could save an estimated $14.2 million over the two-year budget cycle, and tuition increases could raise $72 million over that time.

But that will not be enough.

Under the governor’s proposal, NSC would face a cut of $4 million next year and $5.4 million the year after that, compared to this year’s $13 million in state support.

Nine years after its creation, Nevada State College is still a fledgling institution. It’s got 3,000 students, two buildings on 500 acres of desert, and a tenuous hold on its future.

UNPRECEDENTED GROWTH

It was not supposed to be this way.

For two decades, as Nevada topped the nation in growth, state spending kept pace. Dollars for higher education more than doubled from 2000 to 2009, and enrollments grew by 30 percent over that same time. Programs were added, buildings erected, and a new college sprouted in the desert.

NSC opened in 2002 with 177 students. They attended classes in a remodeled vitamin factory practically on the side of a mountain at the far south end of Henderson.

It was supposed to grow into something like the California State University institutions, with the University of Nevada campuses in Las Vegas and Reno becoming more focused on research, like the University of California institutions. Such research, the theory goes, brings economic diversification and hi-tech business to an area.

"The idea was for there to be a three-tiered system" says James Dean Leavitt, chairman of the Board of Regents. "It’s believed that you can deliver education cheaper at a teaching college than you can at a research institution."

But NSC’s supporters say it never got the necessary funding start. Di Mare says the college got only $624,000 in startup funds from the state, while similar schools in other states get anywhere from $10 million to $65 million.

Still, NSC grew like gangbusters. In its second year, it had 500 students, then 1,200, 1,500, 2,000, topping out at 3,000 this year. If that growth rate continued, the school would be larger than the University of Nevada, Reno in a decade.

As it grew, so did its budget, as state support more than quadrupled from 2004 to this year.

Over time, the college is supposed to get cheaper per student. But NSC still receives more state money than the University of Nevada, Las Vegas on a per-full-time-student basis.

Costs are coming down, though, as enrollment climbs.

The problem so far has been where to put everybody.

The college moved many of its nursing programs and its administrative functions to a series of leased buildings in downtown Henderson. It opened a new, state-of-the-art building on its campus two years ago, supplementing the remodeled vitamin factory. It produced a master plan that envisioned dozens of buildings, dormitories, sports teams, and as many as 25,000 students.

Its graduation rate climbed, its pass rate on the state nursing exam soared, and more students were sticking around for their second year of college.

Maybe, the optimists said, there could even be a Nevada State College campus in Reno someday.

SMALL, FAMILY FEEL

Chris Harris, 32, seems an unlikely disciple for NSC.

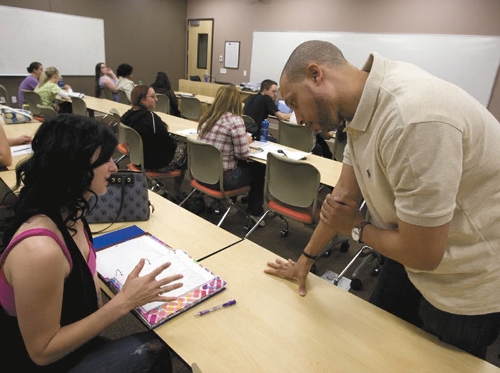

He grew up in New Jersey, attended Boston University, played receiver on the football team, left when the university cut its football program, and ended up graduating from Rutgers. He went on to get his master’s degree from Cornell, and a doctorate in communications from the University of Miami, where he studied rap music.

Last year Harris accompanied a friend to a conference in Chicago, where he happened to run into Di Mare. She sold him on NSC.

"I was just very impressed with the mission at Nevada State," he says, and he quickly latched on to the school’s mission to serve the underserved.

He preached this message at a recent meeting of the higher education system’s governing Board of Regents, which will decide what cuts are necessary as a result of less state funding. Harris told regents that his parents went to state colleges, and that NSC serves a niche that the state’s other schools can’t.

He said the college’s small faculty feels like a family, and its students tend to take their education seriously, which was not always true at large universities.

In an interview later, Harris says that he joined NSC because he was excited by the possibility that the small communications department might one day become a major course of study there.

To do that, the college must grow. But even if the college survives the latest round of cuts, growing is out of the question in the near future.

Because of earlier cuts, NSC has already cut three dozen positions and dozens of class sections. As of this year, NSC has 42 full-time faculty and 134 part-time faculty. Even for those students who get in, graduating on time is becoming difficult as it gets increasingly difficult to obtain required classes.

STUDENTS REVOLT

Sebring Frehner is trying to do something about that.

Frehner, NSC’s student government president, and student leaders at other Nevada colleges and universities, have organized protests — including one sizeable effort in March in Carson City — and are lobbying in key lawmakers’ districts.

The Nevada Student Alliance, a coalition of student leaders from around the state, has in the past supported tuition and fee increases to help offset cuts. A full-time student at NSC will pay about $1,800 per semester in the next academic year — halfway between what students at the community colleges and the universities pay. That cost is up more than 40 percent since 2007, and if further proposed fee increases go forward, the cost would rise almost $1,000 a year.

Students say their support for further increases will only come with a condition: Lawmakers must put more money into higher education.

Students say tuition and fee increases are like a tax increase on the poor, an assertion their detractors dismiss as ridiculous. Fees for classes are just that: user fees, they say, not taxes.

Still, Frehner and his colleagues say students can hardly afford to pay more, despite the relatively low tuition in Nevada.

That is especially true at NSC, Frehner says. Federal financial aid data show the average annual household income for dependent students there is $18,000. This semester, almost two-thirds of the students seeking degrees at NSC applied for financial aid, and almost half receive it.

The school needs more money, not less, Frehner says: "With proper funding, we would have a nursing college building instead of working out of a leased property."

Proper funding would allow the school to continue to grow, adding programs and new majors, he says. And taking some of the burden off UNLV would, ultimately, lower the cost of higher education in Nevada while producing more college graduates.

Closing NSC outright would, in theory, save the state $13 million, the amount it got in state appropriations this year.

"Then you’d basically have 3,000 students who’d have to figure out on their own what to do," Frehner counters.

There likely wouldn’t be room for those students at any other state schools, either. They’re going through budget cuts, too, and expect their enrollments to shrink because of the proposed cuts.

NSC could also be merged into either UNLV or the College of Southern Nevada. That would involve eliminating NSC’s administration, but keeping the students, if there’s room for them.

A higher education system analysis estimated that such a merger could save more than $4 million a year.

FITTING IN

Velanie Williams, 24, recently graduated from NSC with a degree in psychology. She wants to go on to graduate school and study clinical psychology. One day, she hopes to work with the mentally ill. Nevada has long suffered from a shortage of those who work with the mentally ill.

If not for NSC, Williams says, she might never have gotten a degree anywhere.

When her grades at Vo-Tech High School suffered after she contracted a lengthy and mysterious respiratory illness, she graduated with a C average.

And as a teenager, Williams never planned on going to college. No one else in her family had, so why would she bother?

She first met with NSC recruiters at a mandatory college fair while still in high school. Later, on a visit with her mother to the school in 2004, she was not impressed. Back then, it was just the remodeled vitamin factory.

"Mom," Williams recalls saying, "this is not a real school."

That opinion changed as she talked to people there. She enrolled, and liked the small classes and the individual attention from teachers.

She’s convinced that she wouldn’t have succeeded at a large university, even if her high school grades had been good enough to get in.

"The large university is really intimidating to me," Williams says.

Which is why Di Mare, the college president, is fighting so hard.

She has a long history with state colleges, earning both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees within the Cal State system before getting a doctorate from Indiana University.

She has taught and held administrative positions at California State University, Los Angeles and later at the startup Arizona State University-West.

While in Arizona, Di Mare heard about neighboring Nevada’s efforts to expand higher education, and she paid attention.

"When I saw they were building a state college, I said, ‘That’s a state that knows what it’s doing,’ " she recalls.

She joined Nevada State College in 2007 as the provost, and took over as president last year.

She says she’s passionate for the state college and its mission to serve low-income, first-generation and minority students who might not otherwise fit in.

If the proposed cuts go through and the college survives, Di Mare will still have to eliminate more positions, reduce pay, increase tuition and cut 130 more available class sections.

If that happens, graduation rates will tumble, class sizes will increase, advising will be eliminated and, she says, more people could drop out.

Enrollment will inevitably plunge. College officials will give priority registration to students with declared majors, potentially shutting out students who have not figured that out yet. Other students likely won’t be able to afford the fees anymore, and some won’t be able to get the classes they need because there won’t be room.

For the students who cannot go to NSC because of the cuts and fee increases, it’s unlikely most would go to college at all in the near term. Out of state colleges would be too expensive, and there won’t be room for them anywhere else in Nevada, either.

Contact reporter Richard Lake at rlake@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0307.

Editor’s note: Gov. Brian Sandoval’s budget proposes major cuts in funding for public schools and higher education. This series takes a closer look at those potential cuts, the effects they may have on students and how educators are preparing to deal with them.