Foothill High School seniors ask special-needs classmates for prom dates

Prom never entered his mind, not even when he rolled to the ledge and saw rose petals strewn over the school’s wheelchair ramp, down to her. Ben Bunker instinctively turned the other way.

At the direction of a friend, though, he moved past the petals to a thin, graceful blonde standing at the bottom, surrounded by a ring of roses. All the colors Meagan Baker could find. She held a bouquet of other assorted flowers, the names of which she doesn’t know, except for the sunflower.

She knelt and "he got bright red," Meagan recalls in her detailed recounting of asking Ben to prom.

She handed him a piece of paper. She’d scribbled her phone number and a question mark, and told him to call her later. No pressure to answer now.

Before then, they’d never spoken.

"He didn’t call or text all night. Oh, great," Meagan remembers thinking, and laughed at the risk she’d taken in the grand gesture. "I wanted to make it big. Everybody makes it big."

Meagan, a senior at the 2,500-student Foothill High School in Henderson, had noticed others wouldn’t hold the door for Ben, who mostly gets around in a wheelchair because of a spinal-cord tumor. But she would, which Ben noticed.

Meagan wasn’t the only Foothill senior reaching out to someone they barely knew, inviting someone likely to miss Senior Prom. She and other students had approached school staff a few weeks ago, saying they wanted to ask all special needs seniors to the May 12 event in one-on-one dates.

Rae McAnlis, Foothill’s special education facilitator, was immediately onboard but wanted to get parents’ approval before proceeding. All her work has been geared toward something like this, toward peer acceptance. But she feared parents might misconstrue it as a cruel teen joke.

"Every student knows our kids. We don’t push them in a broom closet in a corner at the end of the hallway," she said. One boy, an outgoing senior with fetal alcohol syndrome, gets high fives in the halls and is known as the Mayor of Foothill.

Special education students are not segregated at Foothill. They attend regular classes accompanied by an aid, a program begun five years ago by then-new Principal Jeanne Donadio.

"The general ed kids learn tolerance," Donadio said.

And the special ed kids? The principal pauses before continuing: "They feel a little more normal."

TRYING TO FIT IN

While not a special education student, Ben Bunker has tried to hold on to normalcy by staying in school even though countless surgeries have left him barely able to walk. His parents gave him the option of online schooling, but he refused the easy out.

"A lot of things have already been taken from him," said his mom, Becky Bunker. "He used to run all over."

And an awkward age is even more awkward for him. Ben’s mom had urged him repeatedly to take a date to the prom. He refused.

Then Meagan opened the door.

Ben didn’t simply call Meagan with his answer. He responded in style, writing a letter on a poster and taping seven candy bars to it so their names replaced some of the words.

"I’m no ‘Airhead,’ so of course I’ll say YES! It will be a ‘Almond Joy’ to go with you," it said, in part.

Since then, Meagan has come early to school every morning, waiting for Ben at the corner where his parents drop him off.

SPECIAL REQUEST

The prom invitations for special education seniors came via a group serenade to the tune of Hootie and the Blowfish’s "Only Wanna Be With You." Two senior girls rewrote the words for the surprise:

You and me,

We come from different worlds

We will dance, we will sing,

We just want to go with you,

And feel the joy you bring.

The students then individually asked their prospective dates to the prom. Some invitees didn’t understand. "I have things to do that night," one said.

Most, however, like Cassidy Cooper, said yes.

Cassidy is a sophomore who mentally will never advance beyond third grade, according to her mom, Nora Petersen. She desperately wanted to go to prom with a cute boy, senior Marc Harris. She asked him a week prior but he declined since he had a date. But that date, Kali Grinder, agreed to give part of the night to Cassidy. And after the group song ended, Marc popped the question while Cassidy’s mom watched in the background.

"Someone’s treating her the way she treats everyone," said Petersen, careful to keep her distance until Cassidy came over.

"What happened?" Petersen said to her daughter. "What did he ask you?"

Cassidy whispered something into her mom’s ear, controlling her smile but not her glowing cheeks.

"Are you excited?" Petersen asked.

Cassidy forgot to whisper this time. "YES," she said, grinning wide and exposing her braces as she hugged Petersen’s arm.

Kali, whom Petersen describes as "gorgeous," wasn’t so lucky with her invitation of another special needs student.

"He said I’m not his type," Kali said after being turned down.

A LITTLE THOUGHT GOES A LONG WAY

The gesture paid off for Cassidy and her family, said Petersen, who admits her high school self wouldn’t have had the sensitivity to look beyond her own prom night.

"I think I’m more excited than Cassidy will be," said Petersen, who took her daughter dress shopping at Dillard’s immediately after school. "Cassidy couldn’t wait."

Mom reveled in the mother-daughter experience she thought would be missed.

"Cassidy is not a girly girl, so this is kind of fun," Petersen said while applying mascara to Cassidy’s twitching eyelids. Lola, Cassidy’s 4-year-old sister, sat on the sink, helping her mom like a nurse handing tools to a surgeon. Cassidy’s long pink dress hung from the shower rod.

While her father was uneasy about the dance when the school called for his permission, his misgivings eroded the night after the school serenade.

"Cassidy came running into the garage when I pulled in from work. ‘Guess what? Guess what?’ " James Petersen said.

All the special education kids met their dates at prom, but Meagan picked up Ben, who was ready with his slicked back short hair, olive green button-up shirt, matching plaid tie and black slacks. To top it off, an ivory vest wrapped his chest, matching Meagan’s cream-colored dress. Gold, leaf-shaped earrings dangled from her ears.

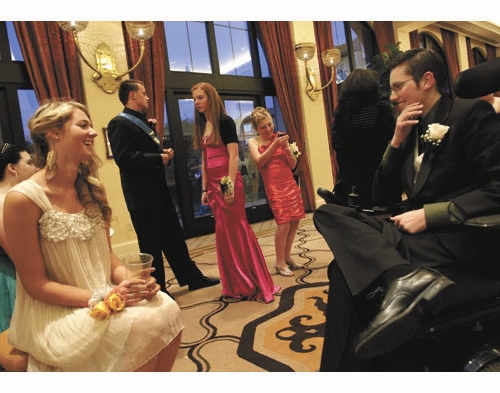

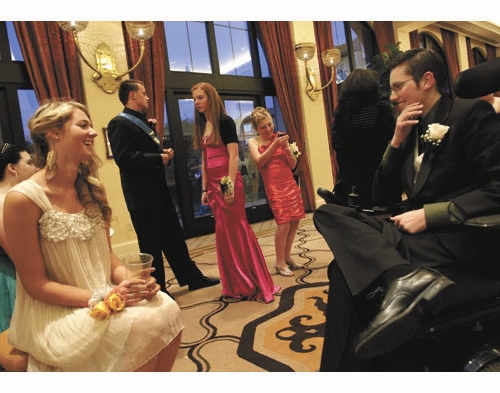

They arrived at Lake Las Vegas’ Westin Hotel for prom at 7 p.m., a fashionable hour late, and made their way into the ballroom.

Ben pushed himself up out of his chair and – quivering under the strain – put some ice into a cup for his date’s drink.

Others in their group had already arrived. Some danced, like cognitively impaired Ashley Campbell, who was quick to list the music she loves: Bon Jovi, Journey, Backstreet Boys. But autistic Christian Ramirez couldn’t handle the noise and pulsing lights. He sat in the hallway with his mom and older sister.

"I was hoping he’d have a better experience than I did," said his 24-year-old sister, Violet Ramirez, who was dateless for her prom. "But he had the experience – and a date."

The dance was over within a couple, quick hours and each couple went their own ways.

But not Meagan and Ben.

They went to dinner at Bellagio and meandered through the casino’s indoor garden, surrounded by spring flowers – a fitting end to a date that began with a rug-of-roses request.

But would it be back to normal come Monday?

Ben’s mom, Becky, worried just that while driving him to Foothill on Monday morning. Would Ben be rolling to school alone or would Meagan be at the corner to talk with and walk him in, as she had in the two weeks leading up to prom?

"She was there," Becky said. "I was wondering, but she did.

"She did."

Contact reporter Trevon Milliard at tmilliard@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0279.