Clark County schools run up legal bills fighting court rulings

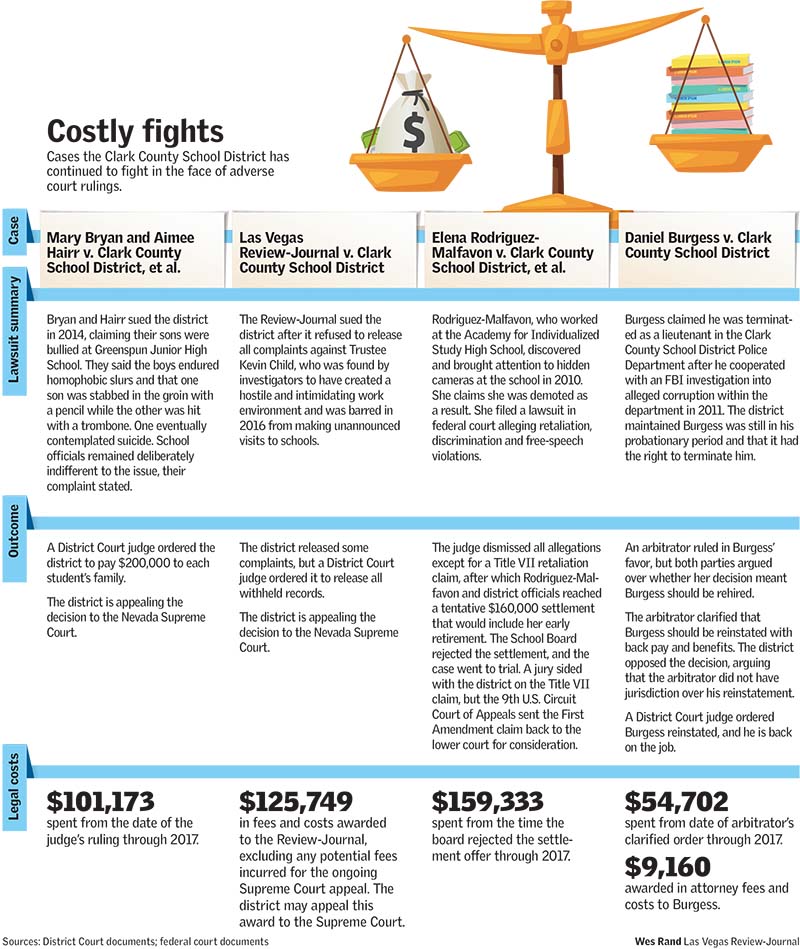

Aimee Hairr and Mary Bryan wanted the Clark County School District to acknowledge mistakes in handling their sons’ bullying in 2011. They sued the district and were each awarded a $200,000 settlement.

Dan Burgess was hoping to return to work with the school district police after acting as a whistleblower in a corruption investigation. When the district disagreed with an arbitrator’s order to reinstate him, the battle landed in court.

The Las Vegas Review-Journal wanted to shed light on complaints against Trustee Kevin Child, a publicly elected official whom the district had quietly investigated for alleged improper behavior. The newspaper sued for related documents.

The common thread in these cases: The school district chose to continue fighting in court after initial decisions went against it. The fights have already cost more than $160,000 — much of it in outside attorney fees — and that figure will grow as the cases drag on.

There could be other cases like these, and additional bills. The district denied a public records request for information on all such cases, citing confidential employment information and attorney-client privilege, among other factors.

Critics see what they consider hardball tactics by the district as a waste of taxpayer dollars in hope of exhausting the plaintiffs’ finances.

“As a taxpayer, it makes me disgusted that they can still keep on blocking the charges and that this law firm is using the school district as a cash cow,” said Bryan, whose award in the bullying case was appealed to the Nevada Supreme Court, where it is pending.

But district officials and their defenders counter that they fight such cases only after weighing likely damages and appeal costs, as well as the principle of the law and the risk of setting a bad precedent.

“We look at the principle of the law, and whether there (were) principles of the law that were decided upon in court that were bad precedent for the district,” said Carlos McDade, the district’s general counsel. “In those cases, we try to get those reversed, because we don’t want a bad decision in one case to result in bad decisions in future cases.”

Pushing back in bullying case

Hairr and Bryan, the mothers in the bullying case, sued the district in 2014 over claims that their sons were tormented at Greenspun Junior High in Henderson but the district failed to address the matter.

A District Court judge ordered the cash settlements for both families after three years of litigation, but the district appealed. The cost for an outside legal firm since then: $101,173 through December.

“We disagree with some of the rulings that the judge made on the law that have a great impact on the trial,” McDade said

Hairr and Bryan say they are appalled by the decision as taxpayers. They argue that the district could have headed off the long legal battle.

“Honestly, we probably wouldn’t be in court if they would’ve said, ‘The dean handled this wrong. We apologize,’” said Bryan, adding that she considers the district’s legal strategy a “good-old-boy system” designed to “protect each other at all costs.”

Elena Rodriguez and her attorney, Tick Segerblom, have a similar view.

Rodriguez is the plaintiff in a complex case alleging discrimination and First Amendment violations by the district. The case dates to 2012, when she claimed that she was demoted for pointing out that the presence of security cameras in her school was not adequately disclosed.

Segerblom, a state legislator (and current Clark County Commission candidate) who has taken on the district in a number of cases over the years through his private law practice, says the district has a set method of fighting “tooth and nail” to send a message to other prospective whistleblowers.

“They should not be saying, ‘We’re going to fight every case because we want employees to know that if they claim they’re being picked on because they’re whistleblowers, that they’re going to pay hell before they take any money,’” Segerblom said.

But Julie Underwood, former general counsel for the National Association of School Boards and now a professor of education law, policy and practice at the University of Madison, Wisconsin, said school districts are often targeted with insubstantial lawsuits in the hope they will cave in and settle.

“Honestly, most school districts don’t have the money or the extra personnel to actually engage in that kind of behavior,” she said, referring to the tactic of exhausting a legal adversary’s financial resources.

Underwood said districts have a responsibility to be good stewards of public money and must conduct a cost-benefit analysis to determine whether it’s worth appealing a decision they feel is unfair.

Fears of ‘bad precedent’

“Sometimes a school district may get sued for something that they truly believe is wrong, and they for some reason may lose at a trial court level,” she said. “And then they want to make sure that they appeal — not just because they don’t want to set bad precedent for themselves, but they also have an obligation to the rest of the public schools in the nation, or in the state if it’s a state issue.”

The Review-Journal sued the district in 2017 when it failed to provide complaints against Trustee Kevin Child requested under Nevada open records laws. The district stressed the need to protect employees from retaliation.

When a Clark County District Court judge ordered the school district to hand over all the requested documents, the district appealed to the state Supreme Court.

If the district loses again, that could prove costly. A District Court judge already has awarded the Review-Journal more than $125,000 in fees and costs associated with the case, a figure that could increase with the cost of the appeal process.

“The school district is cutting educational spending at the same time it’s throwing away money to conceal allegations against Trustee Child,” Review-Journal Managing Editor Glenn Cook said. “This foolish decision is denying voters important information about Trustee Child’s behavior while taking resources from schools. Sunshine in government is far less costly and serves the public’s interests.”

Dan Burgess, a school district police lieutenant, claimed he was fired for being a whistleblower in a corruption investigation.

But the district fought on even after an arbitrator determined in May 2017 that Burgess should be rehired with back pay. From that date, it racked up $54,702 in outside legal fees before ultimately losing the battle.

Even when outside firms aren’t used, the district often must pay plaintiffs’ attorney fees and costs if it loses. In Burgess’ case, it was ordered to pay $9,160 in such costs, according to court documents.

Adam Levine, an attorney for the Police Officer’s Association of CCSD, attributes the district’s refusal to back down to one person: Edward Goldman, an associate superintendent in charge of the district’s Employee-Management Relations Division.

“When it comes to management relations matters, the decisions are not made by the attorneys in the school district’s legal department. They’re made by associate superintendent Goldman,” Levine said. “He gives them their marching instructions, and they’re obligated to carry them out, no matter how inconsiderate or ridiculous they are.”

Goldman declined to comment. McDade, however, said he was responsible for the legal decisions.

“Segerblom and Levine make their living off of suing government entities,” he said. “The opinion that you got from them is what you can expect them to say.”

In the meantime, Bryan and Hairr are awaiting another day in court.

“It’s just mind-boggling to me, but we’re willing to wait as long as we can,” Hairr said. “We’re at the mercy, obviously, of the system.”

A previous version of this article contained an incorrect title for Tick Segerblom.

Contact Amelia Pak-Harvey at apak-harvey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4630. Follow @AmeliaPakHarvey on Twitter.

Expert advice

While the School Board does not have to approve every legal action taken in court, members are regularly updated on legal matters.

“It’s just one of those things where we rely on legal counsel quite a bit when it comes to those things because we’re not in the hearings,” said Trustee Chris Garvey. “We’re not going through all of the depositions and everything like that.”

People may conclude that it’s cheaper for the district to pay plaintiffs off rather than fight a decision, Garvey argued. It’s difficult to discern the difference between those who want to scam the system and those who were really hurt.