CCSD teachers face another month of distance learning challenges

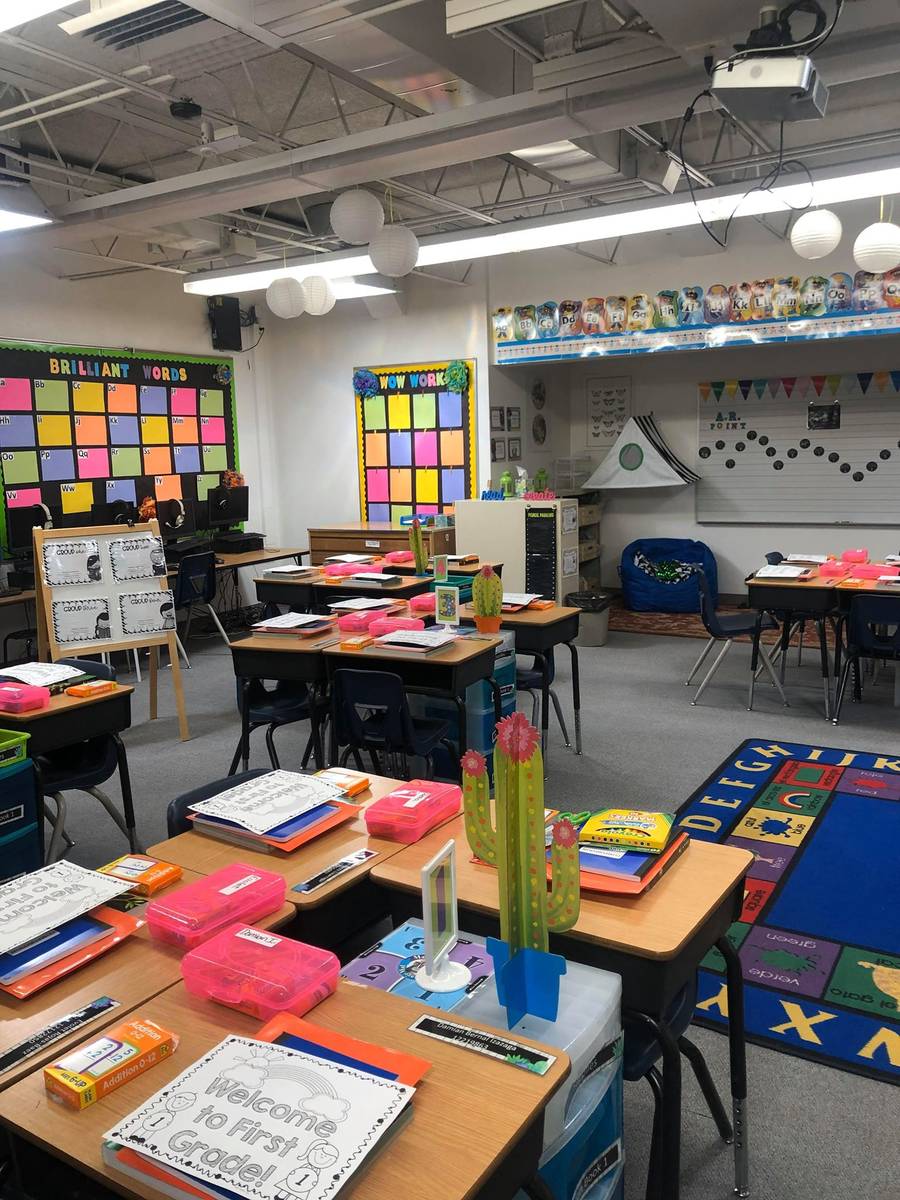

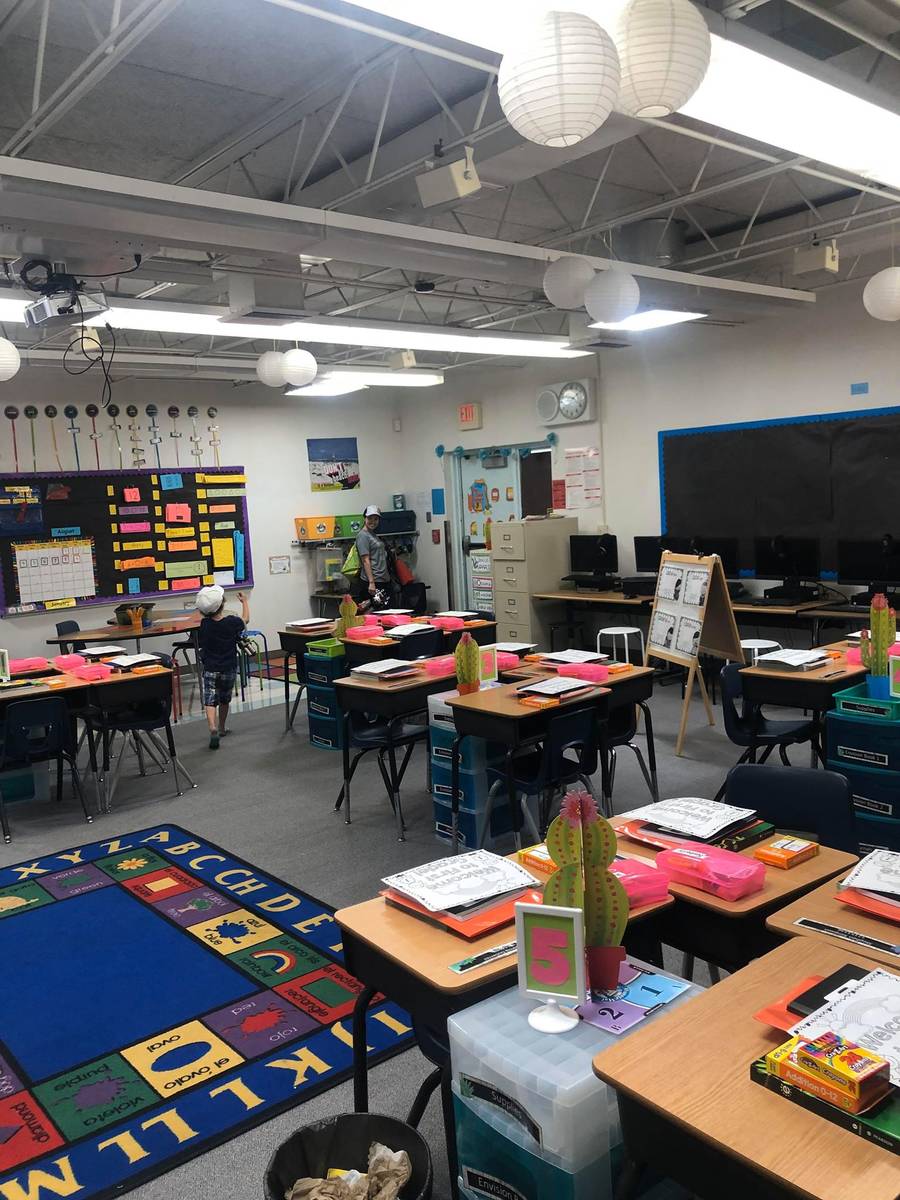

Before school began last year, first-grade teacher Fernanda Lima Gibson enlisted her family to clean and decorate her classroom to make sure it was a welcoming environment for students. Seven months later, she misses that vibrant space as she leads lessons through a computer screen.

“I never thought I’d miss the loudness of the classroom,” she said Wednesday. “Teaching virtually is so quiet, and I don’t get a real grasp if they understand the concepts. I don’t get to witness the lightbulb moment when their face lights up because all their hard work paid off and they know how to solve a problem that was challenging before.”

The challenges of keeping students engaged and on a par their classmates will be with all Nevada teachers for another month or more after Gov. Steve Sisolak on Tuesday extended his emergency closure of the state’s schools through the end of the school year.

Reacting to the move, many teachers and parents say they’re aware that keeping kids on track with learning will be difficult. But many are first mourning what they’ve lost this year, including graduation and promotion ceremonies, classroom time and a chance to say goodbye.

“I never would’ve imagined the school year would be done and all assignments would be virtual,” said Gibson, who teaches at Herron Elementary School in North Las Vegas. “… I just can’t help feeling there was always more I could’ve shown them.”

District to update on its plan

The Clark County School District’s plan for the rest of the school year, which ends on May 20, is expected to be unveiled at Thursday night’s School Board meeting, district officials said late Wednesday. The district is expected to continue food distribution per the governor’s order and maintain its current distance learning strategy, which relies in part on distributing Chromebooks to students who otherwise are unable to reach online lessons.

Superintendent of Public Instruction Jhone Ebert said in an interview Wednesday that her chief concerns are the same as they were when schools closed on March 15: First, students who rely on school meals must be able to access them. Next comes students’ socio-emotional well-being.

“Kindergartners are used to coming to the classroom and getting a big hug from their teacher. That has completely shifted,” she said.

Curriculum and distance learning are largely in the hands of local school districts, she said, with the Department of Education acting as an outside set of eyes when issues of equity arise. To that end, she said it’s essential for districts to be transparent about the access gaps that COVID-19 has exposed to receive help.

But Ebert said she is open to ideas about shaping future learning to alleviate some of the impacts the school closures have had. Ebert said some educators have raised the possibility of “looping” — a practice wherein students stay with one teacher for two years, instead of one — to help ease the transition back to the classroom in the fall.

Teachers also might need to conduct assessments at the beginning of the year to gauge what students know after the disruption to their classroom time this spring. Ebert said. For some 60,000 to 95,000 Clark County students who haven’t been in contact with their teachers since schools closed, these disruptions might deepen existing inequities.

“As we look at what has transpired, we need to more than ever meet children where they’re at,” Ebert said. “When we go back, we need to understand that learning is a continuum. The skills and knowledge our students have, we assess that and move forward from there.”

Ebert also noted that online learning does not necessarily mean an inferior education, saying there are examples of Nevada schools that have done it well for years.

Down in the education trenches, some teachers have other concerns.

Shana Hyatt Stott, who works with credit-deficient high school juniors and seniors at Eldorado High School, said that even though much of their curriculum was already online, her students have struggled with technology issues like broken cameras and temperamental internet connections that have added to their anxieties about school. Some are also battling personal and family troubles at home, she said.

Her classroom was a family-like environment where students helped each other, she added. Without that kind of support, she said she worries some of her students will lose motivation.

‘So close to graduation’

“My biggest fear is losing kids who are so close to graduation,” Stott said.

Her seniors have been particularly disrupted, she said. Some have missed out on sports scholarships because of closures. But others may end up benefiting from changing college admissions criteria that have dropped the ACT and SAT requirements.

For juniors returning to high school, Stott said, there is some concern about learning loss, though she said it’s not insurmountable if parents keep them reading through the summer.

“In the grand scheme of things, they’ve lost about four weeks of instruction,” she said, referring to the fact that the final two weeks of the year are devoted to final exams. “They’re going to have to teach some concepts before they can get into new ones next year, but I don’t think it’s going to put us super far behind.”

At Odyssey Charter School, a blended learning school where students are only on campus for one day per week, the transition to a completely online curriculum has still had its challenges, teacher Tracy Edwards said.

One has been the lack of opportunity for students to work on group projects that develop socio-emotional skills. As an alternative, she said she’s planning activities that rely on parents and siblings for connections instead.

Still, she said she is worried about the possibility of learning loss as the number of kids engaging with distance-learning materials drops. With schedules upended and many parents laid off, some of her students are finding themselves in turmoil at home, possibly becoming the caretakers of their younger siblings, she said.

Her fifth graders probably won’t have a promotion ceremony, she said, though she hopes to honor them virtually or provide some other kind of closure that’s important to parents and teachers too.

“We’re used to having a beginning, middle and end of the school year,” Edwards said. “Kids grow not only academically, but socially. We see where they started and where they end up.”

^

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at 702-383-0218 or aappleton@reviewjournal.com. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.