Agassi, investment team to help charter schools in U.S.

There are big ideas, and then there are Big Ideas.

Building a $40 million college-preparatory charter school from the ground up in less than a decade? That’s a big idea.

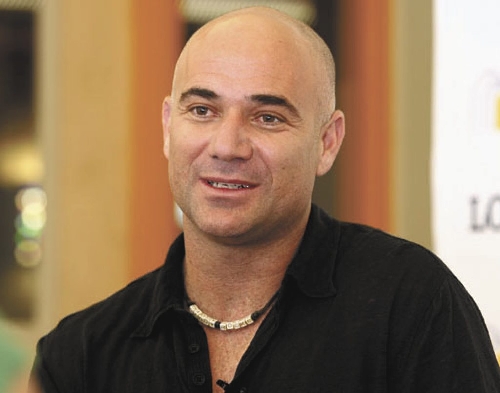

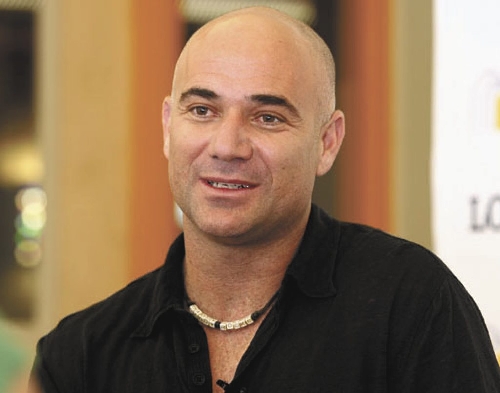

Investing hundreds of millions in new schools for 40,000 students nationwide? That’s a Big Idea — one born of a partnership between tennis great and local charter-school developer Andre Agassi and Bobby Turner, chairman and chief executive of Canyon Capital Realty Advisors in Los Angeles.

Agassi and Turner will announce to day that they’re launching the Canyon-Agassi Charter School Facilities Fund, an investment group designed to help some of the nation’s 5,400 charter schools and their 1.7 million students find permanent school buildings.

The partners already have drawn investments from Citigroup and Intel, through its Intel Capital investment subsidiary. The Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, a Kansas City-based entrepreneurship think tank, has signed on as well. Canyon-Agassi executives say they’ve received commitments that, combined with a "moderate amount of leverage," will finance $500 million in new building or retrofitted space for 75 top-performing charters and 40,000 students nationwide. Because of securities regulations, the partners declined to discuss specifics on investment time horizons, amounts and other details.

The partnership’s first deal involves campus financing for the year-old KIPP Philadelphia Elementary Academy. The campus is scheduled to open in August. The partners are weighing other opportunities nationwide, including in Las Vegas.

Agassi said the fund’s investment model will spur billions of dollars in additional charter-school development and hundreds of thousands more charter-school seats once it’s "fully executed and proven" in three to four years.

"The implications could be dynamic and conversation-changing," said Agassi, a Las Vegas native and founder of the Andre Agassi College Preparatory Academy in West Las Vegas.

HOW GROUP MAY HELP SCHOOLS

To understand how the Canyon-Agassi fund might change the charter-financing debate, start with the niche it’ll serve.

The fund will help charter schools, which are public schools that operate independently from school districts, bridge the gap from opening to facilities ownership. Unlike traditional public schools, charter startups aren’t guaranteed classroom space or building funds. Traditional public schools can tap into property tax revenue to finance new construction, an option that is off-limits for most charters.

Without dollars to build dedicated facilities, charter schools launch in abandoned store spaces, church basements or nonprofit offices, and must pull together financing to buy or build true classroom space. That’s a tall order given the funding gap charters face: A 2010 study from Ball State University found that charter schools on average receive $9,460 per pupil, compared with $11,708 for conventional counterparts in the same state. That’s a 19.2 percent funding difference.

"Most states leave charters high and dry when it comes to facilities," said Eric Premack, executive director of the Charter Schools Development Center, a California group that provides technical assistance to charter startups. "It’s very painful for charters financially. They have to dig into their operational funding stream, and that’s generally not adequate to cover both operating and building costs."

Enter the Canyon-Agassi fund. The group will build new schools or retrofit existing properties for high-performing charter schools looking for environmentally friendly permanent space. Schools will lease the buildings until they reach full occupancy. Canyon-Agassi then will help operators get permanent financing to buy the buildings via New Markets Tax Credits, tax-exempt bond offerings or money from the U.S. Treasury’s Community Development Financial Institutions Fund.

Agassi said the fund will work with the top 10 percent of charter school performers and focus on markets with dense and diverse populations, relatively low real estate costs and fairly high per-pupil education funding. Top prospects include Philadelphia, Baltimore, the District of Columbia, New Jersey and Tennessee. Las Vegas is a possibility as well, depending on the land costs of a specific deal, Agassi said. The partnership isn’t yet planning any local projects. Nevada has 27 charter schools. Officials with the state Department of Education didn’t respond before press time to a query seeking details on Nevada-specific charter funding gaps and total enrollment.

FINANCING FACILITIES A PROBLEM

Education experts say the Canyon-Agassi fund targets the overriding obstacle to charter-school success.

"By far, the biggest barrier charter schools face is getting access to decent facilities. It’s something a lot of communities are trying to figure out right now," said Robin Lake, associate director of the University of Washington’s Center on Reinventing Public Education. "It’s a big distraction trying to figure out how to finance facilities, and it takes away from schools’ instructional focus."

Few options exist for operators seeking permanent facilities, Premack added.

A handful of states — Nevada’s not one of them — require school districts to share space with charters. But most districts say they’re too full to accommodate startups, and maintenance fees can run so high that renting on the open market is cheaper anyway, Premack said. A few states provide lease aid, and there’s a federal grant program designed to encourage investments similar to Canyon-Agassi’s.

"But at this point, financing is a pretty thin patchwork," Premack said. "Most schools are left to rent facilities on the open market, and it’s financially crushing in many states."

SUCCESS, TROUBLES AT AGASSI PREP

Few people are as familiar with the intricacies of charter school development as Agassi.

He opened Agassi Prep in September 2001 with 150 students — none of whom was at grade level in math, reading or writing — in third, fourth and fifth grades. Agassi lobbied tirelessly to raise more than $40 million to build the school’s campus at 1201 W. Lake Mead Blvd., kicking in millions from his own fortune and gaining contributions from local philanthropists and a bond from the city of Las Vegas.

Today, the school serves more than 650 students from kindergarten through 12th grade. It graduated its first class in May 2009 and sent 100 percent of those grads on to college (ditto for the class of 2010).

But the academy had its share of startup troubles. Its teaching staff operates on annual contracts rather than tenure, and the school saw almost total teacher turnover in 2003 and 2004. And a 2004 Clark County School District review found violations of state laws related to personnel and reporting of student information.

Still, by 2005, Agassi Prep’s middle school was the only junior high in Clark County to earn an "exemplary" designation under the federal No Child Left Behind Act. Its elementary school won the same designation in 2007.

"It’s a big learning curve from an operational perspective. We didn’t really get it right until three years ago," Agassi said. "Operators have to go through so many hard lessons. I was fortunate enough to raise a lot of money to make up for my mistakes. The fact that I can take that experience and identify partners who know how to cure problems as opposed to treating them — it’s living a dream."

Turner has experienced his own charter school frustrations.

Turner is on the board of the Pacific Charter School Development Corp., a California charity that helps charter schools find and finance facilities. In Turner’s six years with the corporation, the group has helped 37 charters serving 15,000 students find space. But with 30,000 youngsters sitting on charter school waiting lists in California, Turner "realized how big of a failure we were."

"Here I am, struggling after five or six years of building schools, and we hadn’t done much to scale the issue," Turner said.

But Turner had an epiphany while reading Agassi’s 2009 autobiography, "Open." The book charted Agassi’s professional and personal life and included a discussion of his experiences with Agassi Prep. Turner, who has partnered with basketball great Earvin "Magic" Johnson since 2001 to invest nearly $2 billion in urban residential and commercial projects nationwide, thought Agassi might have a few good ideas.

"We were both dwelling on our failures, and it takes that kind of DNA to really be successful in this business," Turner said. "Whenever you deal with a novel business model, you have to educate traditional capital."

So far, traditional capital is buying in.

Citigroup, the fund’s largest investor, called the partnership "inspiring."

Intel, which has invested more than $1 billion in education initiatives worldwide in the past decade, said the Canyon-Agassi fund would further its school-aid efforts.

Contact reporter Jennifer Robison at jrobison@review journal.com or 702-380-4512.