Documentary examines Rancho High School race riots during civil rights era

North Las Vegas police sprayed mace into a school bus full of students.

A police helicopter made an emergency landing at nearby Smith Middle School after a student threw a rock into its tail rotor.

One student who had leukemia died after being maced.

Racial riots, resulting in emergencies like these, became so prevalent at Rancho High School during the late 1960s and early 1970s that the National Guard was called in. The guard opened a substation at the North Las Vegas campus, positioning officers on the roof with shotguns in hand. Police constantly patrolled the school on Harley-Davidson motorcycles.

“What happened was real surreal,” said Lizzard Griffith, who was a student at the time.

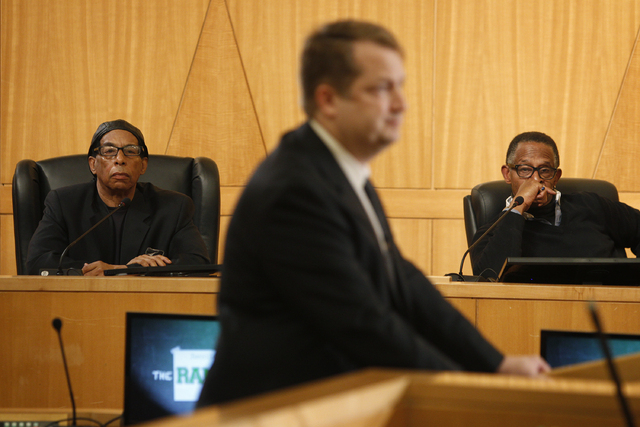

He joined six of his former classmates and a Rancho teacher Friday at the Clark County Government Center for a panel discussion about the racial tension that boiled over in their urban school, a reflection of what was happening nationwide.

Joining the panel was Antonio Fargas, the actor who played Huggy Bear in the 1970s TV show “Starsky and Hutch” and who hosted the 2012 documentary “The Rancho High School Riots,” which brought the panel together Friday.

Director Stan Armstrong graduated in 1972 from Rancho, shortly after the riots peaked. From 1967 to 1974, riots happened once or twice a year, according to the documentary.

“I don’t think too many people realize how and why it happened,” added Griffith, describing the school as a microcosm of the racial tensions that gripped a nation rocked by the civil rights movement, political assassinations, economic inequality and the Vietnam War.

Racially integrated schools were still an adjustment for much of the country at that time after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in 1954 that having separate public schools for black and white students was unconstitutional.

School segregation had been prohibited in Nevada since 1872, according to forum moderator and former University of Nevada, Las Vegas political science instructor Martin Dean Dupalo.

“But that was just on paper,” said Dupalo, noting that Las Vegas schools were still segregated by circumstance.

Black families lived in a certain part of town and attended the schools zoned for their neighborhoods. Whites lived elsewhere and attended their zoned schools.

Rancho was an exception. The high school, third-oldest in Clark County, was a “truly diverse school,” which created a tension among students, Armstrong said.

Jerushia McDonald-Hylton remembers well, recalling the words spray painted on her family’s home: “Nigger, get out of our community. We’re going to kill you.” Her mother and four siblings had moved into a Caucasian neighborhood near the school and feared for their safety every day walking to and from Rancho. The Black Panthers, a community-based, militant civil rights organization, heard about their circumstances and would watch over the family and walk the children to school.

“Rancho should’ve been a model for integration,” said Fargas, a Las Vegas resident. “But outside forces created this cauldron.”

The panelists talked of Black Panthers coming on campus. Police pulled over a school bus of black Rancho students, arresting those on board. Students would go home every night to hear about racial riots across the country on the news, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the fight for civil rights.

“Black students wanted to be a part of that progress,” said Assemblyman Harvey Munford, D-Las Vegas, who was a teacher at the time and remembers the staff “walking on egg shells.”

“There were a lot of angry black students on campus,” Armstrong said. “A lot of them had a misguided anger.”

The violence being pushed on students from the outside made its way into the classroom, according to Michael Brophy, who remembers being part of the BUCK hats. BUCK stood for Brothers United Caucasian Klan.

He was caught in class when a riot broke out. A mob burst through the door. Typewriters were thrown. He remembers trying to protect his female black teacher and dropping female students out the window to safety.

After that, he made sure to never be in class when word of a riot was spreading that day. He would skip class “because you had to fight. Even the non-fighters had to fight, or you’d be pummeled.”

It didn’t matter how you felt, he said. There was no choice. Black students punched Caucasian students and the Caucasian students beat black students.

“It was like a war zone,” McDonald-Hylton said.

“It was just chaos,” Griffith added.

Above all else, it was complicated, Fargas said.

The documentary and Friday’s panel discussion will play together on Clark County Television throughout February, which is Black History Month. The package will air on Feb. 2 at 6 p.m., Feb. 3 at 7:30 p.m., Feb. 4 at 2:30 p.m., Feb. 5 at 2 a.m., Feb. 6 at 7 p.m., Feb. 7 at noon, Feb. 8 at 7:30 a.m. and Feb. 9 at midnight. More replays will be scheduled throughout February with the schedule available at www.ClarkCountyNV.gov.