Carpenter 1 fire a year later: Another fire season has arrived

It was born a year ago with a lightning strike and evolved into a wall of flames that chewed up trees and brush and scorched 43 square miles of the Spring Mountains.

Beyond the blackened pine and juniper trees that dot Kyle and Trout canyons along with streaks of red fire retardant, there remain stark reminders of the Carpenter 1 fire, the blaze that began July 1, 2013, and quickly raged out of control some 50 miles west of Las Vegas.

A year later one community doesn’t have running water and won’t anytime soon. Popular hiking trails on Mount Charleston remain closed.

Flash flooding and erosion are ongoing dangers.

However, the fire might be remembered today more for how its aggression was halted — by human forethought and a deluge of rain.

And as the fire season begins anew, an ongoing drought weighs heavily on the minds of residents and firefighters who know the risk of a new wildfire is only a spark away.

TROUT CANYON STILL DRY

It’s slow going up the dirt and rock Trout Canyon Road to the small community of about 20 homes where David Mallory has lived full time for the past eight years.

For-sale signs hang outside about half of the properties.

“Our property values have plummeted,” Mallory says from outside his home about 50 yards from the edge of the blackened tree forest left by Carpenter 1.

It wasn’t just the fire that caused property values to drop. It was the flooding.

On Aug. 30, workers from the Las Vegas Valley Water District had just finished patching a 50-year-old 3-mile-long pipeline that stretched into the mountains and tapped a natural spring inside a cave. The hoped the pipeline would return running water to the community after residents had been forced for weeks to truck in water.

But then the flash flood came.

“It was louder than a train,” Mallory said.

The 69-year-old retired land surveyor laughed as he recalled how authorities were holding a meeting in Pahrump letting residents know that running water would be working in a few days.

“I called my wife, who was at the meeting,” he said. “I told her the pipeline was gone and she wouldn’t be coming home that night.”

The flood rose 15 feet high and 40 feet across through a wash that abuts the end of the community, near his home, Mallory said. It washed out state Route 160 and kept Mallory’s wife, Debbie, from getting to Trout Canyon.

Standing a few feet from the now dry wash last week, Mallory pointed to a 20-foot piece of the old water pipeline bent in half around a tree.

That was as close as the community has been to running water in a year.

It was also the day federal firefighters were finally able to declare that the Carpenter 1 fire was under control.

COSTLY SOLUTIONS

It will likely be another year, at best, before a new pipeline gets built.

That’s if the recently formed Trout Canyon Land and Water Users Association can cut through all the bureaucratic red tape, said Bob McCormick, a Trout Canyon property owner and Henderson businessman.

McCormick heads the association that was formed after residents realized that without an association, getting a new pipeline would be near impossible.

While different government agencies have been helpful in pointing the association in the right direction to get funding for a new pipeline, McCormick has found that the process to be extremely slow.

“If we were a populated community or if there had been a large destruction of property, we would have received” federal emergency funding to make such repairs, McCormick said.

But because only a couple of dozen homes are in Trout Canyon, getting funding has been a slow process.

Instead, those who could afford it had to purchase plastic tanks — some as large as 1,500 gallons — to fill with water and pumps to run it into their homes, McCormick said. That alone could cost close to $5,000.

At least two residents have left because they couldn’t afford it, McCormick said.

The one saving grace was that one property owner allowed an old water well to be restored and opened its use to the community. And residents who are willing to pay a $50-a-month fee can use it to fill up drums and then siphon water back into their tanks on a daily basis, McCormick said.

The alternative is trucking in the water over an 11-mile long rocky road, which some residents still do.

McCormick is holding out hope that a “goodwill benefactor” will come in and front the money for a new pipeline until government funding is obtained.

But what concerns him even more is that the U.S. Forest Service no longer has a bladder pool filled with water in the community as fire season begins.

“It’s a huge concern. History proves we are in a very dangerous situation,” McCormick said.

The threat of a new fire and more flooding remains as ominous as before Carpenter 1, he said.

SPARKED BY LIGHTNING

A day before lightning struck on the western ridge of the Spring Mountains, sparking Carpenter 1, 19 Forest Service “Hotshot” firefighters were killed battling a blaze in Arizona.

That weighed heavily on Ron Bollier’s mind.

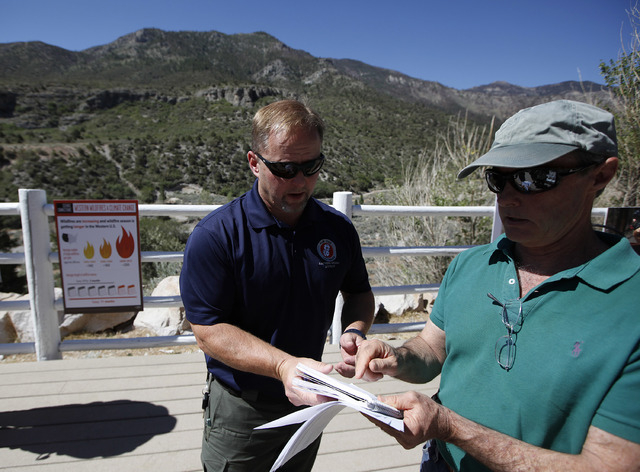

Bollier, a former Hotshot firefighter himself, is the Spring Mountain Recreational Area fire management officer for the Forest Service.

He recalled sending crews in to extinguish two of three fires discovered in Carpenter and Trout canyons after the lightning storm. The third was in such a remote location that only water carried by helicopters could be used to suppress the flames.

Bollier wanted to bring in heavy air support based in Mesquite, but those planes were already committed to fight the Yarnell Hill blaze in Arizona. The helicopter suppression wasn’t enough.

Bollier wanted to get crews to the fire, but the terrain was steep and difficult to reach by foot. There were no landing spots for helicopters.

So, fueled by years of dried brush heaped on top of more dried brush, the blaze climbed to the tops of trees and spread wildly.

The fire was so intense that when it reached the top of the ridge of Trout Canyon, it began to spread downhill into Kyle Canyon, threatening the Mount Charleston community.

Meanwhile, it also spread down toward Trout Canyon Road.

Evacuation orders were given. Hotshot crews along with Bureau of Land Management, Clark County, Nevada Division of Forestry and other firefighters were deployed to stem the blaze and protect property in both canyons.

containment, fuel reduction

The strategy for battling forest fires is mostly about containment.

Fire retardant dropped from the air is used to slow the fire. Another method used is “back burning,” when firefighters set a blaze that will spread toward the fire, consuming the brush or “fuel” that would feed the fire. Without fuel, a fire will die.

Both methods helped stop Carpenter 1 from overtaking homes in Kyle and Trout canyons.

But fire officials such as Bollier and residents like Mallory, along with politicians such as County Commissioner Chris Giunchigliani, who owns a vacation home in Kyle Canyon, all point to the heady decision years ago to conduct a “hazardous fuel reduction” around the two communities.

The $10 million federally funded program allowed the Forest Service to clear away much of the brush that had built up around the communities for decades. The money was obtained through BLM land sales in the county.In all, 2,150 acres of land was cleared of fuel around the communities in Kyle Canyon, Lee Canyon, Cold Creek, Trout Canyon, Lovell Canyon and Mountain Springs.

With less fuel, the intensity of Carpenter 1 lessened, allowing firefighters to work on containing the fire and keeping it from spreading to those communities.

The fuel reduction program was finished two years before Carpenter 1 and is widely credited for saving those communities.

EROSION CONTROL

Since the summer of 2013, the Forest Service has been working to restore some of the land and protect against erosion and flooding, which still pose great risks.

Jim Hurja, a soil scientist for the Forest Service, has overseen a heli-mulch on Kyle Canyon to stop flooding.

A heli-mulch is when mulch, made mostly from straw, is dropped in strategic locations inside of a burned area. The straw helps absorb water, which helps slow flooding and encourages re-growth.

But mulching wasn’t done everywhere on the mountain. Most of Trout Canyon is too steep for mulching and federal land laws prevent the Forest Service from performing such treatments in remote areas, Hurja said.

So far no seeding has been done, Hurja said, though analysis of the area will be done repeatedly in the coming years.

As far as regrowth of the trees, it will take decades, Hurja said.

In most areas burned by Carpenter 1, “the idea is to let nature take its course.”

In Kyle Canyon, a new bridge is being built to withstand flooding and work is being done to make the Cathedral Rock hiking trail safe again. Cathedral Rock has been closed since the fire.

The blaze not only burned the trees and brush, but was so intense that it burned roots holding rocks and boulders in place, Hurja explained.

Add falling rocks to the resulting problems of Carpenter 1.

In Trout Canyon, fire management officer Bollier said he’s aware of the need to have a water bladder in the community in case a new fire starts.

But since the loss of the pipeline, a bladder hasn’t been feasible. Instead, a 6,000-gallon bladder was placed in Pahrump. Helicopters based at the North Las Vegas Airport can easily access that water to fight any fires on the western side of the Spring Mountains.

Bollier is also trying to coordinate building a 10,000-gallon water tank in the Trout Canyon community. “It’s just that nothing happens fast,” he said.

seeking improved COMMUNICATION

It’s impossible to know how far Carpenter 1 would have spread if the fuel reduction hadn’t happened years earlier or if torrential rains at the end of August hadn’t poured down on the Spring Mountains.

Bollier said the fuel reduction program remains the best educational tool he has seen in his 35 years as a firefighter.

He also knows that after every fire, there are lessons to be learned.

After Carpenter 1, which wasn’t officially fully contained until snow packed the mountains in December, Bollier said he wants to see communication lines between all agencies, including federal, state, county and local firefighters, opened sooner rather than later.

Back on Trout Canyon, Mallory knows wildfires and floods loom as a danger over the community, especially in the drought stricken Spring Mountains.

And yes, it would be nice if the community had the pipeline up and running, but there are plenty of places in the U.S. and around the world that don’t have access to a water pipeline, he said.

Still, Mallory and his wife stay.

Mallory talked about clean air and how he and his neighbors watched a movie outside on a screen hung outside his home. He spoke about the mountain lion he heard earlier in the morning. He pointed to some green shrubs popping up through the blackened tips of tree trunks. Those shrubs indicate regrowth has already begun, he said.

After Carpenter 1 and the evacuation and the flooding, Mallory’s brother pushed for him to move out of Nevada and to Washington.

Mallory and his wife did some soul-searching, he said. Neither wanted to leave.

“OK, I said. Let’s start living again.”

Contact Francis McCabe at fmccabe@reviewjournal.com or 702-224-5512. Follow @fjmccabe on Twitter.