Berkeley Bunker

Of all the bizarre tales of Nevada politics — and there are plenty of them — none is stranger than the one in which a dead senator, on the eve of his re-election in 1940, was preserved on ice in a hotel bathtub by his campaign aides until the vote was final.

He was Democrat Key Pittman, first elected in 1912. Having hit the end of the campaign trail, the rarely sober senator began hitting the bottle, and subsequently suffered a heart attack in his room at the Riverside Hotel in Reno.

The politician-on-ice story is almost certainly bogus; serious researchers have concluded Pittman was rushed to the hospital, where he died, after the election was already in the bag.

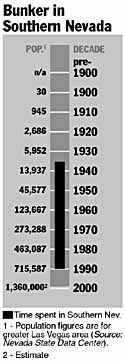

But Pittman’s death did set into motion an equally strange series of events in the career of a serious-minded young man named Berkeley Bunker. He would be celebrated as the first Southern Nevadan, and first Nevada Mormon, to hold national office. Later, he would be accused by his fellow Democrats of the heinous crime of political ingratitude, becoming a party pariah.

Denied a career in the political arena, he returned to Las Vegas and became a successful businessman and the much-loved and respected church leader who would spearhead the final drive to build the Las Vegas Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The Bunkers are a pioneer Mormon family of the Moapa Valley. Martin and Euphamie Bunker moved there from St. George, Utah, in 1877 and established the family ranch at St. Thomas. Berkeley was born there in August 1906, one of five boys and two girls.

When he was 17, his father sold the ranch to the federal government, which was acquiring land that would be submerged by the waters behind Hoover Dam, and bought another ranch near Alamo in Lincoln County. Martin Bunker moved his family to Las Vegas, and divided his own time between there and the ranch. Young Berkeley, impressed with Las Vegas’ modern conveniences, like electricity and indoor plumbing, promptly became a city boy.

“I said, ‘This is for me,’ and I fell in love with town — and I’ve loved it ever since,” he said in a 1988 interview.

He was one of 26 graduates of the Clark County High School class of 1926, and then was called on a church mission to the Deep South. On his return in 1933, he married Lucile Whitehead, a fellow Moapan.

The fall of 1935 was the season of petroleum and politics, as Bunker was elected vice president of the Nevada Young Democrats Club, and leased a Mobil Service Station at the corner of Las Vegas Boulevard and Carson Street. Shortly after that, he opened a Texaco Station at Fifth and Fremont streets.

Bunker’s first foray into politics was in the summer of 1936, when he entered the race for the state Assembly, and was the top vote getter in the primary race.

During his first term in 1937, Bunker astonished everyone by garnering an appointment to the Assembly Ways and Means Committee.

He easily won a second term in the 1939 Legislature, and surprised everyone again when he challenged William Kennett of Tonopah for the position of Assembly speaker, and won.

Bunker had not planned to seek a third term, but at the urging of party leaders, filed for re-election in 1940, and won.

But then Key Pittman died.

Responsibility for naming Pittman’s successor fell on Gov. E.P. “Ted” Carville, who was instantly set upon by a horde of eager applicants, including Pittman’s brother, Vail Pittman.

Chief among the contenders was Review-Journal Editor Al Cahlan. He traveled north with state Democratic boss Ed Clark to attend Pittman’s funeral, and to lobby Carville. John Cahlan recalled in later years that his brother was certain he had a lock on the plum position.

“It was agreed among Carville, Ed Clark, and my brother that Carville would appoint my brother,” said John Cahlan. “This was all wrapped up and apparently ready to be the gift that Carville was to give to Al. No question — none whatever.”

On Nov. 26, 1940, Carville announced his choice — Berkeley Bunker.

“Bunker’s appointment can perhaps be seen as a slap at anti-Mormonism,” said Michael Green, history professor at the Community College of Southern Nevada. “It was also an acknowledgment that the Mormon Church, and its adherents in Southern Nevada, were gaining political power.”

Las Vegas attorney and political watcher Ralph Denton thinks the clamor from the numerous factions in the Democratic Party may have prompted Carville to choose someone who wouldn’t offend any of them.

“How could you knock the appointment?” he said, “Nobody was mad at Berkeley Bunker.”

“The fact of the matter is,” said Bunker, offering his own explanation for the appointment, “I managed (Carville’s) Southern Nevada campaign when he ran for governor… when I was speaker, we worked closely on legislation, and we were very close friends. But why he chose me, I’ll never know. I didn’t campaign for it; I didn’t lift a finger. I was the most surprised man in the state when it came.”

Cahlan, the second most surprised man in the state, spoke no ill of Bunker, but did give plenty of newspaper space to expressions of astonishment and dismay from other Democrats.

With little knowledge of international affairs, and a war already going in Europe, Bunker’s public utterances concerning foreign policy were cautious.

“I shall be a strong advocate for a strong national defense program, but I am not in favor of sending our men to Europe,” he said, “I think the British can win the war with the assistance the United States can render under the lend-lease bill.”

But isolationists became extinct on Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Bunker was in church in Washington, D.C., when he heard of it.

“At lunchtime, we received word … The next morning I went to the House of Representatives — they had called a joint session of Congress. When I walked over to the House chamber, the sergeant-at-arms pulled me out of the line because he thought I didn’t look like a senator; he said I looked too young.” Another senator vouched for him and he was allowed in.

With war under way, Bunker cast himself in the role of gadfly, harshly criticizing plans by Basic Magnesium and the Defense Plant Corp. to build a company town — which would become Henderson. The senator insisted housing also was needed in Las Vegas proper and, as a result, several hundred new houses were built in the Huntridge district, near East Charleston and Maryland Parkway.

Bunker continued the pressure, accusing BMI and the DPC of drawing up a contract that would result in an annual profit to BMI of more than 4,000 percent.

“If the agreement between the Defense Plant Corporation and Basic Magnesium Inc. represents a cross section of conduct on the part of the DPC, I can come to only one conclusion; we are tolerating the existence of an agency of the government that is so corrupt that it would make profiteering in the last war look like petty larceny by comparison.”

Bunker later explained that he tackled the BMI issue because he was concerned that the plant would not survive into the competitive postwar marketplace unless it were put on sound financial and managerial footing from the outset. The BMI complex has survived to this day.

The freshman senator was obliged by law to stand for election in 1942, and to his chagrin, his opponent in the primary was former Gov. James Scrugham, then one of the top Democrats in the state.

Given the caliber of his opponent, his 1,100-vote loss to Scrugham in the primary was a respectable showing. Still, it was his first political setback, and left him feeling “kind of empty.”

Readjusting his sights to a lower trajectory, Bunker bounced back in 1944, announcing his candidacy for Nevada’s lone congressional seat, challenging and beating incumbent Democrat Maurice Sullivan in the primary.

“Bunker surprised the wiseacres by beating Sullivan in his home county of Washoe,” crowed the Las Vegas Review-Journal. The fact that Sen. Patrick McCarran campaigned for him couldn’t have hurt.

The general election, in which he faced silent film star Rex Bell, was a 14,000-vote landslide for Bunker.

The next year, 1945, Scrugham died, vacating the very seat Bunker had once warmed. Gov. Carville again had to name a replacement, and Bunker was a top contender. But Carville had a better idea. He made a deal with Lt. Gov. Vail Pittman; Carville would resign, Pittman would become governor, and appoint Carville to the Senate. The only catch was that he would have to stand for election in 1946.

It was more than Bunker could stand. He announced that he would challenge his former benefactor in the 1946 Democratic primary, a move that he would later admit “was the biggest mistake of my political career.”

Bunker easily defeated Carville, and was expected to trounce Republican George “Molly” Malone in the general elections. Pat McCarran campaigned for him, saying, “I would rather work for the next four years by the side of Berkeley Bunker than any man I know.” The Congressional Quarterly said he was “sure to be elected.” The Las Vegas Review-Journal ran an editorial on the front page center, a gushing endorsement of Bunker.

So fragmented was the Democratic vote that Malone rode to an easy victory — though it should be noted that 1946 was a very good year for the GOP nationwide.

Back home again, Bunker was hired by P.O. Silvagni to manage the Apache Hotel, then one of the best in the city. (The property would later be leased by Benny Binion, and renamed the Horseshoe Club.) Bunker stayed for less than a year, resigning because his duties required him to work Sundays, a day that Mormons set aside exclusively for worship and church activities.

As an LDS bishop, Bunker was much in demand among his brethren as a funeral preacher. And his years in politics had enhanced his oratorical skills. For a deeply religious man, the job of “preaching people into heaven” was quite satisfying.

“I never knew the real heartbeat of the people until I became a bishop of the LDS church. When you hold a funeral, clasp the hand of the dying and prepare for the last rites … you feel the true pulse of the people.”

So, Berkeley joined his elder brother Bryan in the mortuary business.

Bryan Bunker had bought a half-interest in the Howell C. Garrison Mortuary, at 515 Fremont St., in 1944. His partner was Lester Burt, who had been Garrison’s embalmer. Brother Berkeley bought Burt’s interest in 1946, and the familiar Bunker Brothers name was created.

Berkeley Bunker made one last bid for elected office in 1962 when he got his party’s nomination for lieutenant governor. He faced a relative newcomer in Paul Laxalt, but the young man was a ferocious campaigner, according to Bunker, who dubbed him “The Man of War.” Bunker might still have beaten him, said Ralph Denton, but for defectors in his own party.

“A lot of old wounds from 1946 came back,” Denton said. “Many of the old Carville people remembered that, and were bound and determined to beat him.”

In 1988, Lucile Bunker died, and the following year, Berkeley married Della Lee, a native of Panaca. She would care for him as his health deteriorated, until his death Jan. 21, 1999, at age 92.

Among the members of his church, Bunker will certainly be best remembered as chairman of the fund-raising committee that finally gathered the money needed to construct the long-anticipated Las Vegas Temple, the gleaming spired structure at the base of Frenchman’s Mountain.

In 1988, with the temple nearing completion, Bunker made a point of downplaying his role in the enormous undertaking, noting that the fund-raising effort had been started by the late Reed Whipple.

“Las Vegas has been very kind and good to the Mormon people,” said Bunker in 1988. “We have grown and thrived and lived as good neighbors to the Catholics and Jews and Protestants and all denominations without ever a rift.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full