Suicide survivors and those who lost loved ones seek paths to healing

WINNEMUCCA — Jennifer Hood, one of the few marriage and family therapists in this Humboldt County city, had a secret she never told her co-workers, though she sometimes confided in her clients.

“I never shared … that I felt suicidal,” Hood said on a spring weekday as she sat her office staring at raindrops hitting the window. “I was beginning to tell myself that if things got really, really bad, it was certainly an option out there, like the atom bomb.”

The “bomb” eventually went off. Hood tried to end her life with a bottle of pills decades ago.

Winnemucca family and marriage counselor Jennifer Hood opened up about her attempted suicide, which he had kept secret. “If I can’t tell my story, how in God’s name can I expect anyone to step forward and start talking about theirs?” she said. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @rookie__rae

Winnemucca family and marriage counselor Jennifer Hood opened up about her attempted suicide, which he had kept secret. “If I can’t tell my story, how in God’s name can I expect anyone to step forward and start talking about theirs?” she said. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @rookie__raeHood, now 64, has processed her suicide attempt both as a survivor and a therapist. She says her recovery from the crisis and subsequent sobriety made her want to help others.

“There is no shame left,” she said, sharing her story publicly for the first time. “If I can’t tell my story, how in God’s name can I expect anyone to step forward and start talking about theirs?”

It’s estimated that about 1.4 million people in the U.S. attempted suicide in 2017, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. About 47,000 died.

Two kinds of survivors

Suicide ends lives, but it also creates new beginnings for two types of survivors: those who attempt to kill themselves but live and those who must find the will to go on without lost loved ones. Their journeys after the life-altering events are very different.

Survivors speak of shame and confusion that led to their crises but also of the gradual rediscovery of the pleasures and rewards of living.

Hood said she has found relief in helping others on the brink of self-destruction and joy in her family life. Her daughters have made her a grandmother, as evidenced by the children’s artwork affixed to her refrigerator.

On the other end of the spectrum is Jerome Penaranda, 34, of Las Vegas, who has been searching his memory for any signals that he might have missed before his 66-year-old mother, Vivian, overdosed on prescription medication. Her death on June 26, 2017, was ruled a suicide by the Clark County coroner’s office.

He remembers she had been battling health issues and was lonely at times, but he didn’t see any indications that she was thinking of ending her life during their weekly excursions to church and to a Filipino bakery afterward.

“She really didn’t live her life to the fullest,” he said wistfully.

A shrine to his mother

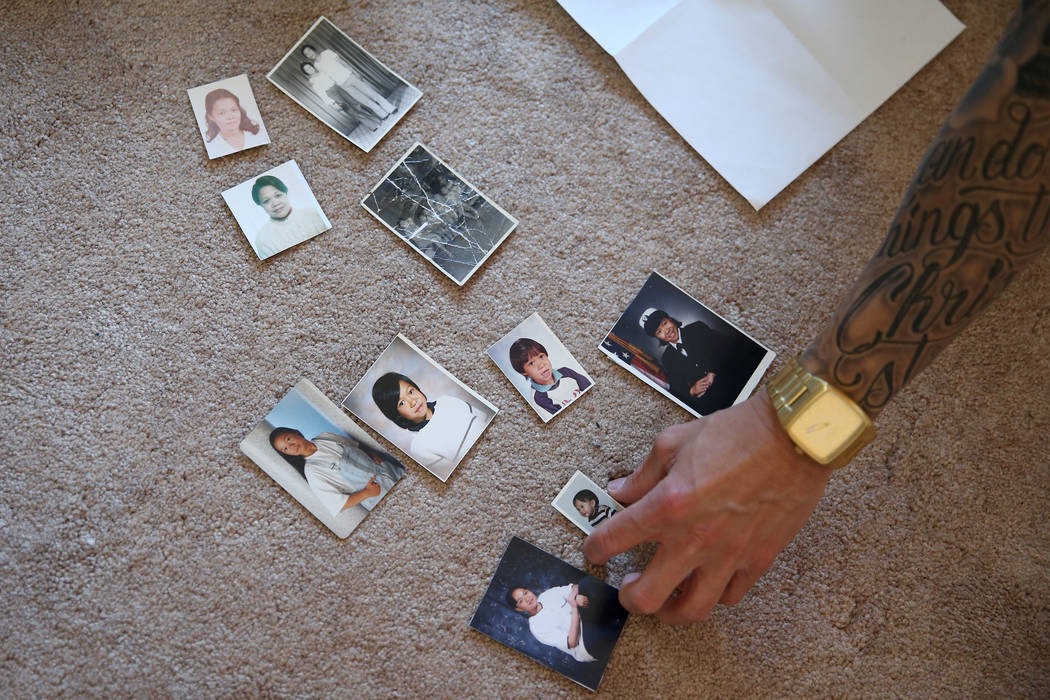

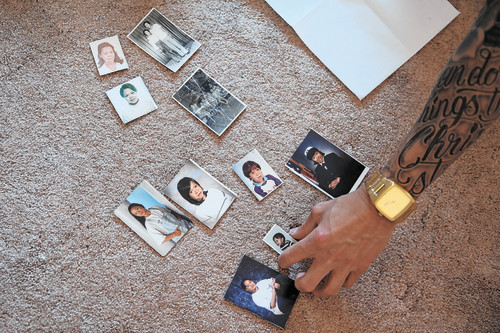

Penaranda keeps his mother’s jewelry in an old cigar box. He keeps a shoebox of cards she sent him. In another room, he created a makeshift shrine of some of her other belongings but after a while took down the portrait that he hung there.

Jerome Penaranda is photographed at his Las Vegas home, Thursday, March 7, 2019. Erik Verduzco Las Vegas Review-Journal @Erik_Verduzco

Jerome Penaranda is photographed at his Las Vegas home, Thursday, March 7, 2019. Erik Verduzco Las Vegas Review-Journal @Erik_Verduzco  Jerome Penaranda shows pictures of his family at his Las Vegas home, Thursday, March 7, 2019. Erik Verduzco Las Vegas Review-Journal @Erik_Verduzco

Jerome Penaranda shows pictures of his family at his Las Vegas home, Thursday, March 7, 2019. Erik Verduzco Las Vegas Review-Journal @Erik_Verduzco Seeing her smile every day was just too difficult, he said.

“I carried the burden of what she did,” Penaranda said.

Chuck and Jeanette Reineck have grieved for almost a year as they come to grips with the loss of their 31-year-old son, Brandon, who ended his life on Father’s Day in June 2018. It’s also put a strain on their relationship, they said.

At a recent support group meeting at Rainbow Library in northwest Las Vegas for families who have lost a loved one to suicide, they held crinkled torn pieces of a blue napkin that they used to rub away their tears as they told their story. They were the only two in attendance this week at the peer support group for those who have lost veteran loved ones led by Chris Jachimiec, an active-duty member of the Air Force who has lost multiple family members and friends to suicide.

“We’re missing a tire,” Jeanette Reineck, who goes by JJ, told Jachimiec in a conference room, its sterile, baby-blue walls echoing the pain the couple shared. Outside, soles shuffled along a linoleum floor.

Without Brandon, life isn’t the same. Now, the two are learning to live their new normal.

“Tomorrow the sun will rise, and we’ll start all over,” Chuck Reineck said.

I think about it and deal with it on a daily basis. Not a day goes by that I don’t think about Hailee.

Jason Lamberth

A different path

The path traveled by the parents of Hailee Lamberth, who died by suicide just two days into her 13th year in December 2013, was different in that their effort to understand her death led to at least a partial answer: They found out that she had been bullied at White Middle School in Henderson and that an online complaint had been submitted through the Clark County School District.

But the school and the district never informed them of its existence.

Jason Lamberth said the discovery of the back story that led to the death of their first-born soccer-loving daddy’s girl was devastating.

“I think the way that her school and her administrators handled the situation … sent her a message that it doesn’t matter if you tell an adult,” he said, tearing up at the memory.

The school district approved a $700,000 settlement in September 2018 after the Lamberths filed a lawsuit over the handling of the case.

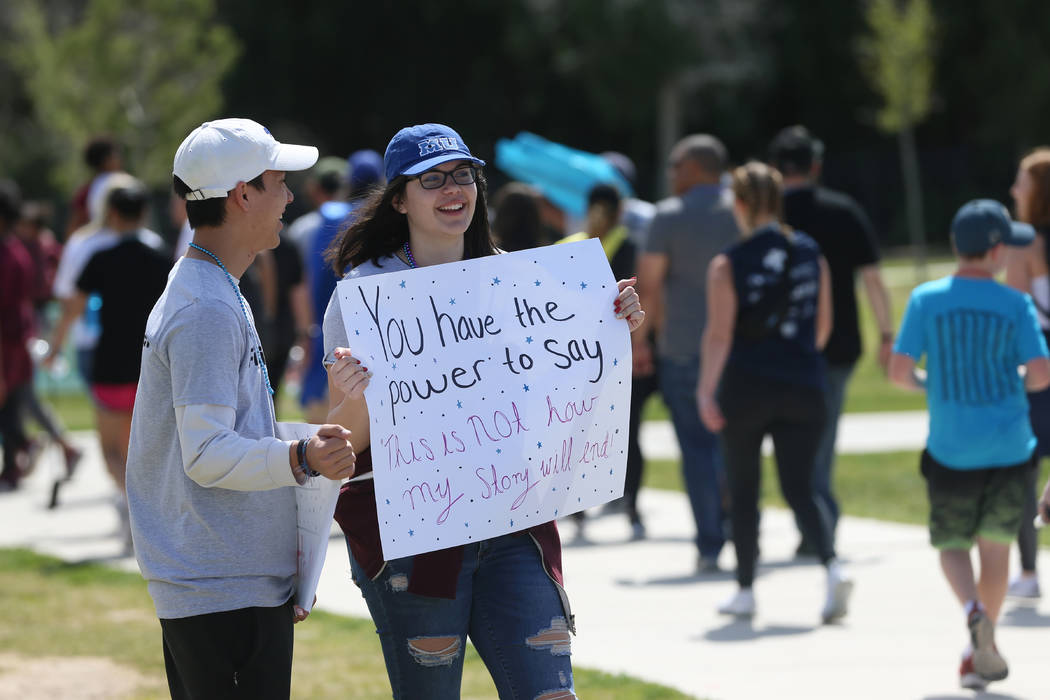

Jason Lamberth participates during the Out of the Darkness Suicide Prevention Walk at Craig Ranch Park in North Las Vegas on April 6. After being bullied at school, Lamberth's daughter, Hailee, died by suicide in 2013. (Erik Verduzco/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @Erik_Verduzc

Jason Lamberth participates during the Out of the Darkness Suicide Prevention Walk at Craig Ranch Park in North Las Vegas on April 6. After being bullied at school, Lamberth's daughter, Hailee, died by suicide in 2013. (Erik Verduzco/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @Erik_VerduzcWith the healing that comes with time, the Lamberths have channeled their pain into advocacy. The family created Hailee’s Hope, a nonprofit that raises awareness for bullying and teen suicide. And they campaigned for and helped pass Hailee’s Law, sponsored by then-Gov. Brian Sandoval, which created the Office of Safe and Respectful Learning in the state Department of Education.

That’s not to say the hurt has gone away.

“I think about it and deal with it on a daily basis,” Jason Lamberth said. “Not a day goes by that I don’t think about Hailee.”

Coming out of darkness

While anyone who has ever lost a loved one has likely experienced similar stages of grief and recovery, those who attempt suicide and survive walk a path less traveled.

Bianca McCall, a Las Vegas marriage and family therapist who runs a certified suicide prevention therapy clinic, said she tells survivors that they might not have wanted to end their lives, only to erase their current circumstances.

“When you have that emotional pain, that distinction is blurred,” said McCall, who runs one of the area’s only support groups for people who attempt suicide.

People participate during the Out of the Darkness Suicide Prevention Walk at Craig Ranch Park in North Las Vegas on April 6. (Erik Verduzco/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @Erik_Verduzco

People participate during the Out of the Darkness Suicide Prevention Walk at Craig Ranch Park in North Las Vegas on April 6. (Erik Verduzco/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @Erik_VerduzcoFor Hood, the Winnemucca therapist, those lines were restored the moment she woke up in a hospital bed, sick from the pills she swallowed and feeling alone and depressed. But as soon as she looked into the eyes of her daughter, who was standing at her bedside, she immediately regretted her attempt. What if she had left her and her other grown daughter without a mother?

“I just remember being flooded with the most intense feeling of wanting to disappear,” Hood said. “I think it was because of the loving tenderness I saw in her eyes that I really began to feel loved beyond all measure.”

She said she went to a treatment center for one month, saw a therapist for about six months after and then began relearning to trust herself.

“I think part of my journey was trying to feel safe in the world and not feeling that the world was going to kill me,” Hood said.

As a therapist, she has lost clients over the years. The first one was a man in his 20s struggling with substance use disorder and depression.

“I remember thinking to myself, ‘I can’t do this work,’” she said. But a supervisor gave her a piece of advice she remembers to this day: “You cannot take responsibility for these people’s successes — they belong to them — and you cannot take responsibility for their failures.”

How to talk to a loved one

If your loved one is showing signs of suicide, don't leave them alone and remove any access to hazardous substances or firearms.

It's important to show that person that there is hope, "that they're not alone, that they're not invisible and that someone cares," said Misty Vaughan Allen, the state's suicide prevention coordinator.

Those conversations should start before someone is in a crisis.

"If you notice any change," Vaughan Allen said, "it's worth exploring what is going on in that person's life, be it emotional, physical or behavioral."

Though it's a myth that talking about suicide will plant suicidal thoughts, Las Vegas marriage and family therapist Bianca McCall does recommend proceeding with caution. If a person is made to feel more isolated by that conversation, it could do more harm than good, she said.

"The most responsible thing is to get them connected with someone who is trained and qualified to talk about suicide," said McCall, who runs a certified suicide prevention therapy clinic.