Rural homelessness issue comes to a head in Pahrump

PAHRUMP — Mary Supple, a glass of Steel Reserve malt liquor clutched in a hand tanned from years of desert living, flung open the door of her battered recreational vehicle and prepared to be uprooted.

“Whoa, baby,” the sandy-haired brunette exclaimed as the early-afternoon sun glared into her bright blue eyes.

Wednesday was moving day, the deadline set two weeks earlier by the owner for her and about nine other homeless people to leave the private property they had temporarily been allowed to occupy.

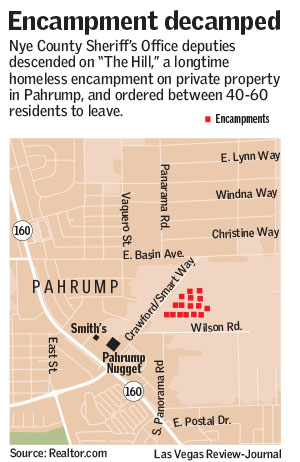

They moved there after they and approximately 30 to 50 others were

rousted from a ramshackle encampment known as “the Hill,” where they had lived for years.

Supple, 59, and her inoperable RV were bound for another vacant piece of land not even a mile away, courtesy of a local towing company that volunteered its services when word got out that the camp residents had been ordered out.

The eviction has forced local officials to address the growing population of homeless living in and around Pahrump despite a near absence of resources.

“It’s put us between a rock and a hard place,” acknowledges Nye County Commissioner Lorinda Winchman, who said the commission is relying on the community to put forth proposals.

“If they’re looking for a partner in the efforts they put forward, there may be something we can do,” she said. “But there are so many questions about cost, … providing shelter and land. We may not have enough taxpayers in the county to foot the bill for something like that.”

Among the members of the public already addressing the issue is Nancy Brown, a pastor at Covenant Lighthouse Church’s You Matter Ministries, which has been providing the encampment with food, water, clothes and transportation for years.

Brown said the fact that authorities are acting after years of looking the other way is encouraging, adding that she will bring up the issue again at the next commission meeting in Pahrump on Oct. 16.

“It’s pushed the community to become proactive, to look at the situation,” said Brown, who plans to propose creation of a community of tiny homes and other possible solutions. “It’s no longer something that’s hidden or being swept under the carpet.”

15 minutes to clear out

Supple had lived on the Hill, a vacant stretch of 160 acreson East Basin Road east of the Pahrump Nugget, for nearly a decade before Nye County code compliance officials contacted the owner, Basin Panorama Investors of Las Vegas.

Officials advised the firm that the encampment was considered a public nuisance and that there were “at least eight pending violations” over living conditions, said Arnold Knightly, Nye County public information officer.

Sheriff’s deputies arrived on Sept. 12 and informed residents they had 15 minutes to collect their things and get out. Those who didn’t would face arrest, they said.

An agreement with the owner of a nearby property allowed the cast-outs to set up shop there, but only for two weeks.

That forced Supple and others to move again on Wednesday, to a series of dispersed sites around the valley.

“It’s bad enough that they’re homeless, but now they’re displaced homeless,” Brown said.

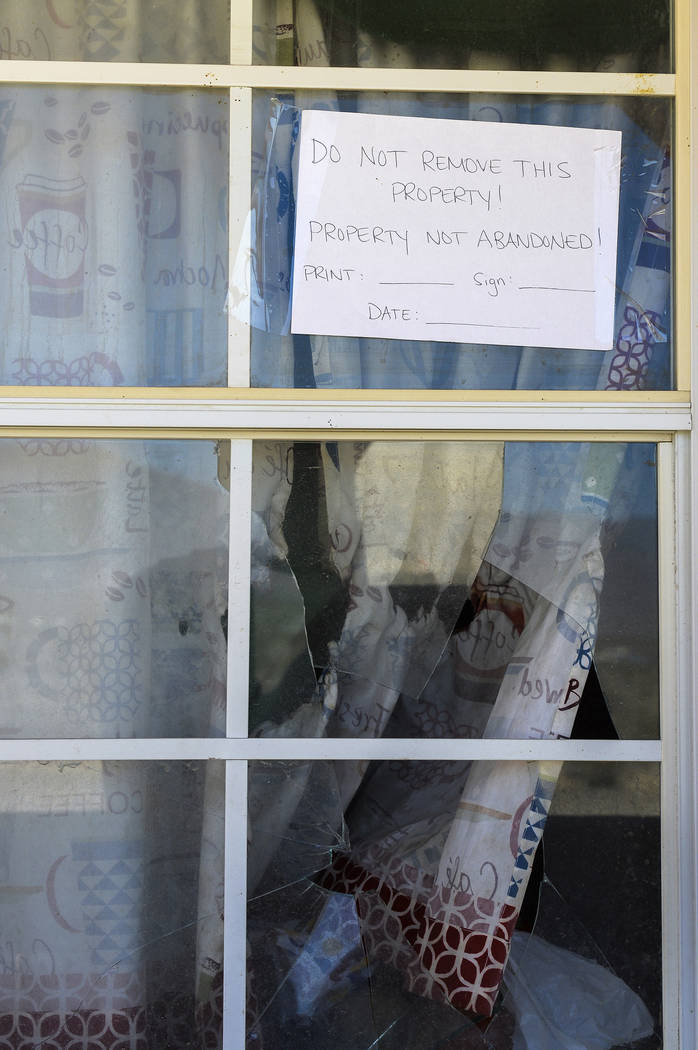

When a reporter visited the Hill a week after the eviction, many of the trailers and shacks were still there, minus the inhabitants.

There weren’t any no-trespassing signs visible, just a for-sale sign, indicative of the $4 million the owner is asking for the property. Attempts by the Review-Journal to contact the company were unsuccessful.

What was left behind told a story of its inhabitants.

Visible inside the humble dwellings were pill bottles, popcorn bags, groceries and cans of beef ravioli. A collection of water jugs, fudge pop boxes and discarded cigarette butts littered the rocky road outside.

A piece of paper blowing like a tumbleweed fluttered by, bearing shaky handwriting that read “Home attacked.” Colorful drawings of maps and the Earth adorned the pages of a nearby notebook.

Outside one run-down trailer without wheels sat a black bag stuffed with clothes and a sign reading: “DONATIONS. The Hill.”

The haste of the residents’ departure was evident. Oatmeal had been left in a pot on a hot plate, and garments hung from clotheslines.

In an effort to formalize their living arrangement, the residents had unofficially chosen a mayor some time back, a man with a white handlebar mustache named Mike Votaw who had moved to the Hill about four years ago.

He’d taken it upon himself to guard the camp along with his Australian cattle dog named Baby Girl and provide food and shelter to newcomers.

Gisele Potter, a 62-year-old who turned a shed into a makeshift house, said that for the first time in a long time she had felt a sense of community.

“I’ve been homeless before. I didn’t feel like I was homeless this time,” she said. “The Hill was my home.”

Ingenuity on the go

The adaptability of the new vagabonds was apparent during a visit to the temporary camp set up after the exodus.

Residents had water stored in blue kiddie pools, which they were keeping cool with generators at a cost of roughly $16 in fuel a day.

Others made shower contraptions: Tim Persson used a mosquito repellent dispenser to spray water on himself; another man bathed under a hose snaking down from a cooler on top of his trailer.

Ashley Hanson, 29, who is pregnant, was ensconced with her fiance in a renovated ambulance.

Hal Davis, a 63-year-old Air Force veteran, had solar panels on top of his recreational vehicle to generate electricity.

“It’s like normal life. It’s just five times harder to haul water, make sure my batteries are charged up,” he said.

The elder on the Hill, a 73-year-old man who chooses to be referred to only as Rich, had lived there for two years. While some residents owned mopeds, he’s the only one with a truck: a Blue Dodge Ram that he used to make ice runs, which he said cost him about $120 a month. He said the residents pool their resources together and share food, electricity and water.

When the police came to the Hill, he said, he packed up his toothbrush, prescription drugs and a few clothes and rolled out.

“I just did what I was told,” he said as he sipped iced tea in front of his trailer, an area decorated with potted plants and cacti. “No sense in arguing with them. I don’t want to go to jail.”

Interpreting the law

Less than a mile from the Hill, attorney Haley Box spent the afternoon on a recent Wednesday taking statements from about 20 camp residents. She called them precautionary affidavits, which would be needed if the nonprofit decided to proceed with litigation.

Potter told Box, who works for Nevada Legal Services, how deputies came to the camp and told them to be off the property in 15 minutes.

“What am I going to do in 15 minutes? Where am I going to take it?” she said of her shed.

Box asked the residents whether anyone had ever told them they couldn’t be at that camp. All responded in the negative.

She noted that Nevada law states that a squatter must be given four days’ notice to leave if the owner wants to regain possession of the property. The owner also is required by law to keep the squatters’ property for 21 days, she said.

“We’re not seeing that here. There was no notice given besides ‘you have 15 minutes; get your stuff and leave,’” Box said, adding that at least two residents had been arrested when they returned to attempt to retrieve their possessions. “They kind of just left these peoples’ properties, everything that they collected, just sitting out there in the middle of nowhere.

“It’s understandable that the landowner wants to get them off, but you have to follow the procedure and protect people’s due process.”

Nye County Sheriff Sharon Wehrly said the owner had asked authorities to give the homeless people 15 minutes, and they treated it as a trespassing case, not a squatters case.

“We went to the DA’s office before any decisions were made, and the decision was made by the DA,” Wehrly said.

Vanessa Maxfield, office administrator for the Nye County district attorney’s office, denied that, saying, “Our office had nothing to do with the decision.”

Wehrly said the sheriff’s office would be a partner in any rehoming resolution for the city’s homeless.

“We’re not callous,” she said. “We have a lot of heart and we have a lot of compassion here, but we also have to go by the law.”

She also said deputies had been forced to respond to the Hill “numerous times” in the past year because of complaints about domestic altercations, neighbor disputes and barking dogs.

“I think we even had one murder up there,” she said.

On the move again

As the tow truck driver hooked up her run-down RV — with spider cracks laced across its windshield, shredded tires and a painted message on one side reading “I Love You Crazy Mary, ” signed “Crazy Dave” — Supple puffed on a cigarette, her jean shorts sagging toward her bright-red toenails.

“We’re warriors,” she said with a toothless grin. “They’re trying to split us up.”

She said she’s been homeless since 2003, when her live-in boyfriend died of a heroin overdose and she had nowhere else to go. She became one of the first residents on the Hill.

Now, she lives alone in her RV with her mama cat and four kittens.

“We wanted to be away from the city, get away from all the B.S.,” she said. “So we don’t get in trouble with the law.”

Nearby, a ginger-haired man with a mullet and goatee asked for help with his generator.

“What do I look like, Bruce Lee?” Supple, who weighs less than 100 pounds, responded with a toothless grin.

Tim Persson and Supple began discussing their immediate futures when a possible solution struck him.

“Superman’s going to save our ass,” she said.

“I wish things were that simple,” he responded. “They dropped a bomb on us, mentally.”

Supple then got down to business for her second move in two weeks. She grabbed her kittens, sorted through a box that held a large pine cone and an Easy Bake Oven.

“The only thing that’s good for is drying my weed,” she said of the latter, tossing it onto another pile.

Then, she hugged Nicole Olivas, who was there with her husband, Jon, to tow her home to another vacant lot.

“You’re like my secretary,” Supple joked in a raspy voice. “You’re my angel, you’ve always got my back.”

A few minutes later, the couple’s white flatbed began to drag the RV, with Persson at the wheel for guidance, across the desert floor.

For a moment, it got stuck in a cluster of creosote bushes, causing the truck’s wheels to dig deep into the dirt.

But moments later they were on their way again, bouncing across the hardpan, bound for yet another way station on the road to an unknown destination.

Clarification: After the publication of this story, District Attorney Angela Bello and Sheriff Sharon Wehrly have clarified that the DA’s office was involved in the decision to consider the campers trespassers rather than squatters. The sheriff’s office received the legal opinion that the campers could be trespassed – or immediately removed — from the property in accordance with the owner’s wishes.

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.

Keeping count

For several years, You Matter Ministries has conducted a weekly census of homeless living on the Hill.

Pastor Nancy Brown said the number of residents peaked at 62 in April, twice what it was in 2014.

A week before residents were ordered out of the encampment, the number was 42, a typical drop-off during the sweltering summer months, she said.

As of Wednesday, three had been relocated permanently to land donated by property owners. Nine others were dispersed to private property on a temporary basis, while others had vanished.