Researchers hope to save endangered Colorado River fish with trip to gym

Behind the locked gate of a government hatchery near Lake Mead, silvery fish swim against a man-made current in a shallow tank resembling a racetrack.

For two critically endangered species that once flourished in the Colorado River, the race for survival now involves a trip to the gym.

“The fish in here are kind of couch potatoes,” said Brandon Senger, motioning to the hatchery’s indoor tanks filled with razorback suckers.

Senger is the supervising fisheries biologist for the Department of Wildlife in Las Vegas. He said the concept of slow conditioning is nothing new. “It started with trout back in the ’70s to try to improve post-stocking survival rates,” Senger said.

FISH DOING FISH THINGS

The razorbacks and bonytails get their exercise in a long tank filled with about two feet of water and equipped with pumps arranged to produce a constant flow with no dead spots. A cinder-block barrier runs down the middle of the tank to form what amounts to a treadmill for fish — an oval track around which the water constantly swirls.

The training tank was set up and stocked with bonytails for the first time a few weeks ago. Already the effort appears to be producing results.

Though the strength-trained fish look about the same as their lazier hatchery mates, Senger said you can feel the difference when you handle them. “They’re a lot more wily and stronger,” he said.

The fish will spend their last 30 days in captivity undergoing strength training in gradually increasing flows. Then they will be turned loose next month to see how they fare against the non-native game fish and other predators that have pushed their species to the brink of extinction.

DOOMED BY DAMS?

The bonytail chub and razorback sucker used to be found throughout the Colorado River system, where they grew at least 2 feet long and lived for decades in swift currents of murky, silt-laden water. Then the dams went up and the suddenly clear, still reservoirs behind them were stocked with game fish.

As hatchery biologist Eric Laux put it: “Suddenly they can’t go where they used to go, and they have all these crazy neighbors.”

With no time to adapt, their numbers quickly plummeted.

The bonytail was added to the endangered species list in 1980, and the razorback joined it there in 1991.

Laux said the bonytail is considered “functionally extinct” because all the fish now found in the wild were put there by people. The silvery fish with the streamlined body doesn’t live long enough to reproduce on its own.

That might sound futile, but researchers insist they are learning from their failures. “They’re not all gone, so we have to keep trying,” Laux said.

STRENGTH IN NUMBERS

Each year, thousands of newly hatched razorbacks, each less than half an inch long, are collected from Lake Mohave and elsewhere to be raised off-river for at least two years. Most of them are gobbled up by predators soon after their release, but some have been known to survive for 20 years or more. There are even a few isolated groups that reproduce in the wild, including a small, self-sustaining population in Lake Mead.

“That’s why we try to make them big. Bigger fish survive longer,” Senger said.

Every fish that is raised and released gets implanted with a pit tag similar to the microchips people place in their pet dogs. Researchers track their subjects in the wild using underwater scanning mats that log the tagged fish as they swim overhead.

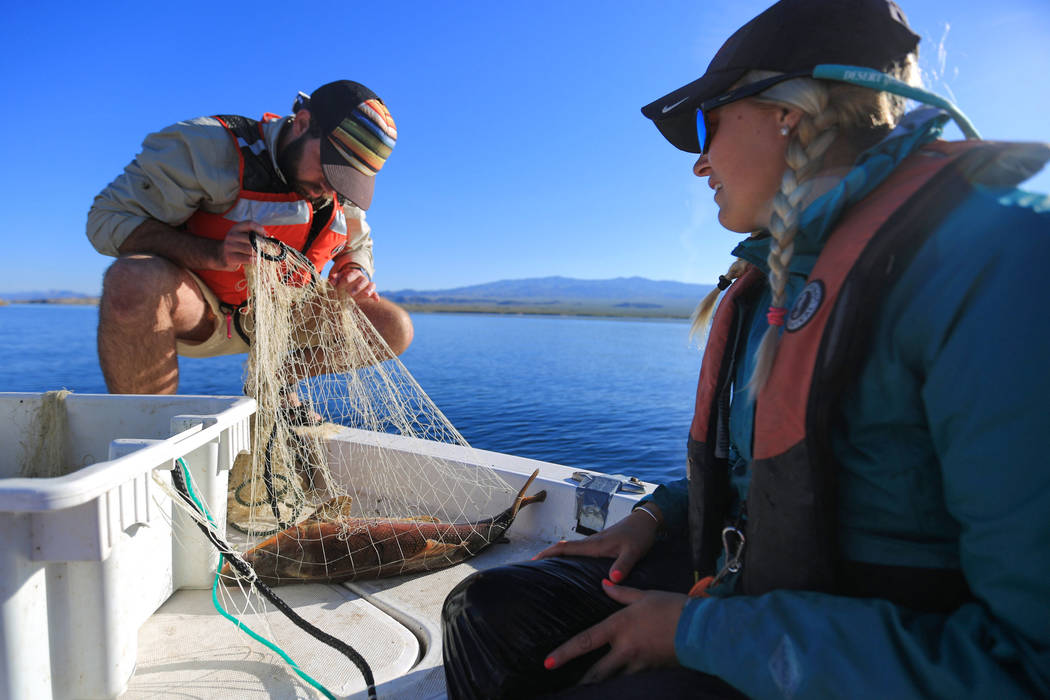

Twice a year, fish are netted and examined in various locations to assess the relative size and condition of the population.

Senger said those regular roundups should give researchers their first clues as to whether the strength training is making a difference, but it could be years before their experiment in survival of the fittest yields any meaningful results.

“Ideally, we will catch these fish again,” he said. “But if we don’t catch them in six months, it doesn’t necessarily mean anything. Biology and ecology work on a very slow time frame that’s beyond our control.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com. Follow @refriedbrean on Twitter.

MEET THE NATIVES

The bonytail chub is a silvery fish with a streamlined body that narrows to the width of a pencil at the tail. It can grow to up to 2 feet in length and live up to 50 years. Once found throughout the Colorado River system, the bonytail is now considered “functionally extinct” with no signs of successful reproduction in the wild.

The razorback sucker is brown and yellow with a distinctive bony ridge behind its head. Adults usually reach 1 to 2 feet in length but can top 3 feet and live for 50 years. Their population plummeted after the Colorado River was dammed, and the species is now considered critically endangered.