Nevadans becoming more accepting of COVID-19 vaccine, poll finds

More Nevadans have warmed to the idea of getting vaccinated against COVID-19 over the past five months, according to a new Review-Journal poll.

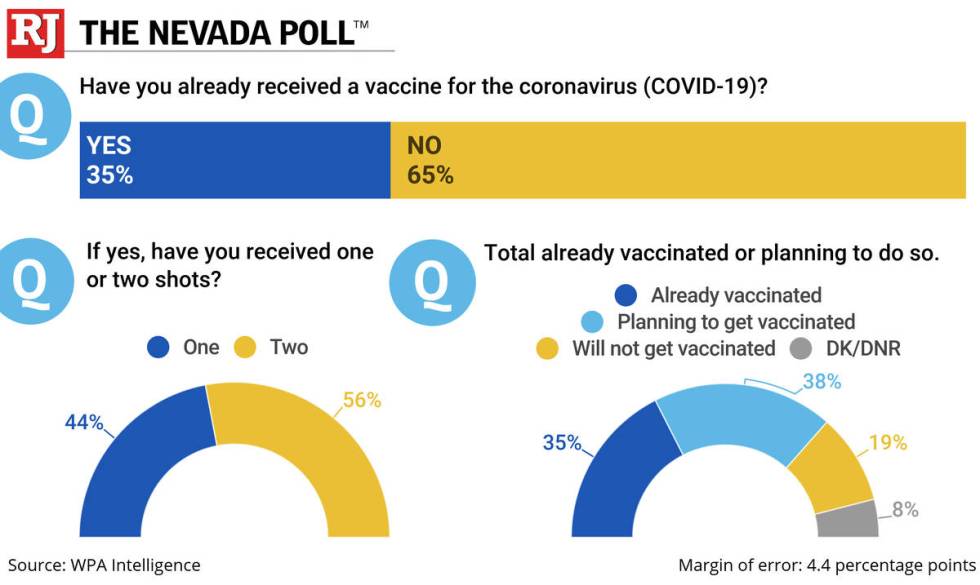

Seventy-three percent back inoculation, with 35 percent already having received a shot and 38 percent planning to get vaccinated, according to The Nevada Poll™, a phone and online survey of 500 likely voters conducted by WPA Intelligence from Feb. 26 through March 1. The survey has a margin of error of 4.4 percentage points.

That’s a gain of 10 percentage points from the 63 percent who said they planned to get the shot when polled in early October, with the converts coming from the ranks of the undecided. Those opposed to being vaccinated dropped just 1 percentage point to 19 percent — still nearly one-fifth of those polled.

“I think there’s a lot more confidence out there” now in vaccines to protect against the coronavirus, Trevor Smith, research director of pollster WPA Intelligence, said of the shifting public opinion. “People are seeing a lot more people getting the vaccine. There’s less fear.”

Arthur Caplan, founding head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU School of Medicine, agreed, describing the shift as “significant.” He believes that many people initially were hesitant to be vaccinated because they didn’t want to be among the first recipients when they thought vaccine development might have been rushed.

“There’s starting to be an acceptance that things look OK. Nobody has grown a third arm or keeled over from vaccinations,” he said jokingly. “So I think that makes people comfortable.”

Herd immunity

With vaccine acceptance higher than 70 percent, the community could be inching toward herd immunity, authorities said, where enough people are immune to the coronavirus to prevent its transmission. They estimate that 70 percent to 90 percent of people need to have immunity for this to happen.

Dr. Walter A. Orenstein says we’re not there yet. He noted that despite the high rate of effectiveness of the vaccines, they are not perfect, and that 1 in 20 people who are inoculated with the Moderna or Pfizer vaccine, for example, won’t be protected.

He described acceptance rates reflected in the poll as a “good step in the right direction, but I think we need to go higher.” Orenstein is a professor of medicine at Emory University and the former director of the U.S. Immunization Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The survey indicates that women have been more concerned about getting inoculated than men. Forty-two percent of men polled said they had been vaccinated, compared with just 29 percent of women. But moving forward, there may be less of a difference: 57 percent of women who hadn’t gotten the vaccine planned to get it, compared to 59 percent of men.

Caplan believes the gender difference may reflect unfounded concerns that the vaccines can affect fertility by altering DNA.

At least one poll respondent mentioned this, saying: “My wife and I still hope to have kids. There is no research that definitively shows how the vaccines will affect fertility.”

Republicans have been less likely to get vaccinated, the poll found, with 30 percent saying they had gotten the vaccine, compared with 36 percent of Democrats and 41 percent of independent voters and those of other parties. Moving forward, three-quarters of Democrats plan to get vaccinated, compared with 43 percent of Republicans and 58 percent of independent voters.

Forty-four percent of Trump voters said they would not get the vaccine, compared with just 13 percent of Biden voters.

“It is ironic, since one of the great things that was done under the Trump administration was the development of these vaccines,” Orenstein said.

Hesitancy fault lines

The survey also exposed some vaccine hesitancy fault lines among various racial groups.

Thirty-eight percent of white respondents said they’d gotten the vaccine, compared with 23 percent of Hispanics and 38 percent of Blacks.

Fifty-eight percent of whites said they planned to get vaccinated, compared with 64 percent of Hispanics and 54 percent of Blacks. However, the subgroup of Blacks was small enough to substantially increase the margin of error, calling into question the finding, Smith said.

Dr. Margot Savoy, an associate professor at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University, said that as physicians and other trusted members of minority communities have begun to advocate for the vaccine, that has “shifted the tide a bit” away from the distrust.

Savoy, who is Black, said she was frank with her patients, telling them as recently as December that she couldn’t recommend the vaccine before she had reviewed the data from clinical studies

“But now we’ve been able to review the data and see how limited the number of serious side effects have been and how many people have now been vaccinated and not had any real serious issues come up,” she noted.

More important, she said, communities are seeing that people who have been vaccinated are avoiding hospitalization and death from the virus.

Wealthier, more educated people were more likely to have gotten the vaccine. Fifty-two percent of those surveyed who had college degrees and household incomes above $75,000 had gotten a vaccine, whereas just 24 percent of those without a degree and with a household income below $75,000 had been inoculated.

Yet across the socio-economic spectrum, poll respondents want the vaccine. Fifty-seven percent of those without college degrees and with household incomes of less than $75,000 want the vaccine, compared with 68 percent of those with a college degree earning more than the threshold.

“We do see numbers that consistently show that the rich are doing better than the poor in the country in terms of access” to vaccine, Caplan said, due to factors that may include education levels and less access to the internet to make appointments.

‘An aggressive side of the flu’

Smith, the pollster, said responses from those who did not want the vaccine primarily reflected concerns about the speed at which they were developed and possible long-term health impacts.

“It was put together too quickly, and it’s just a trial. We don’t know what side effects it could cause,” said one woman who voted for Trump.

A Democrat who voted for Biden also said she was “afraid of the long-term side effects.”

“I don’t trust the politicians or the pharmaceutical companies,” replied a self-described moderate male who voted for Trump.

“I am very healthy. I won’t get it. I drink apple cider every day,” said one 82-year old man who voted for Trump. “This is just an aggressive side of the flu.”

Nevadans also were asked how they thought vaccine should be distributed, with 32 percent favoring prioritizing pre-existing conditions and immune health, 29 percent favoring an age-based approach and 17 percent saying it should be based on employment.

In Nevada, employment has been a major driver of who gets the vaccine first, with hospital workers being the first to get vaccinated, followed by emergency responders and public security personnel. Many other employment groups also are now eligible, along with residents 65 and older.

Those 64 and younger — with or without pre-existing conditions — are not yet eligible for vaccine.

But Caleb Cage, who directs the state’s COVID-19 response, said public opinion is one thing, while sound public policy is another.

“Polls are not necessarily aligned with the scientific ethical and equitable approach that the state has been using from the very beginning, based on CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) input,” he said.

Contact Mary Hynes at mhynes@reviewjournal.com. Follow @MaryHynes1 on Twitter.

The crosstabs attached to a previous version of this story had a typographical error in the age breakdown of poll participants. The error has been corrected in the current crosstabs.