National poetry gathering in Nevada highlights black cowboys

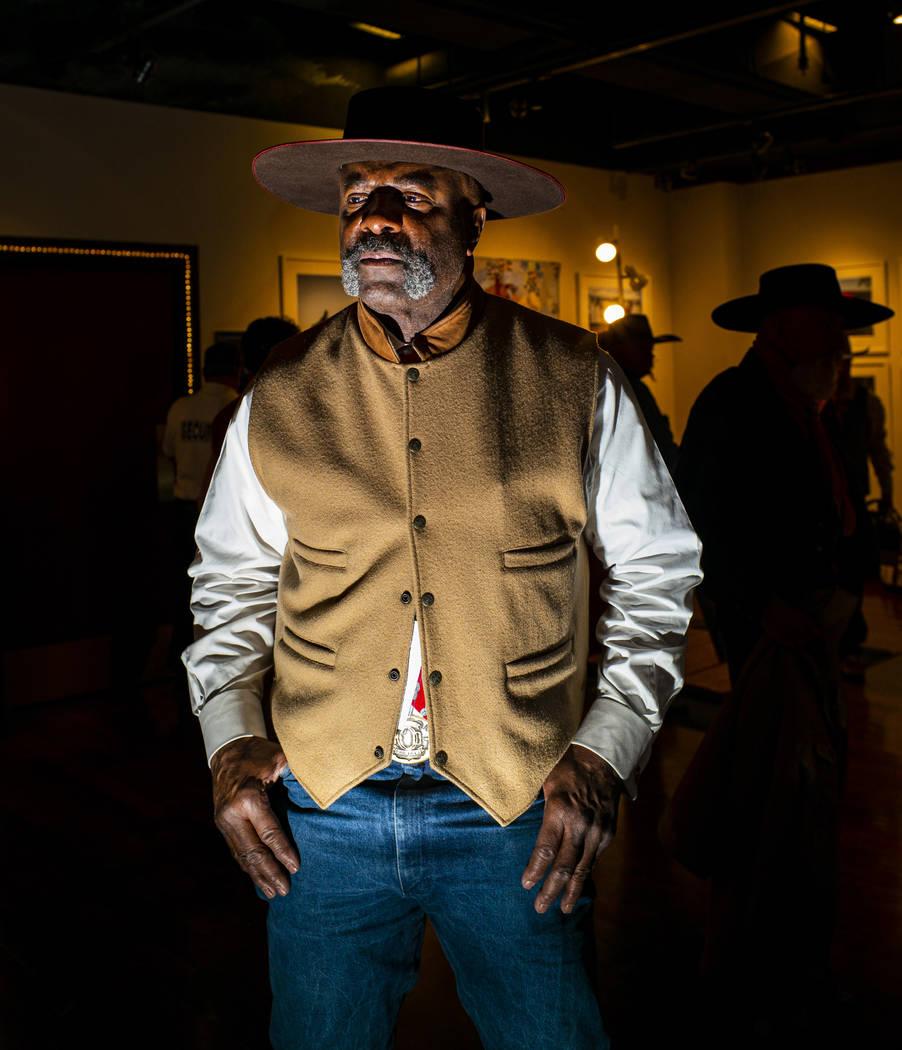

ELKO — The worn spurs on his dust-covered leather boots clink with every step.

Tucked into his faded blue jeans, his white button-down shirt billows, held in by a leather belt with a classic gold buckle.

His hands are leathered, worn by years of handling rope and reins. On his head sits a coffee-brown hat reminiscent of those worn by the vaqueros who roamed these Northern Nevada lands more than a century before.

By almost all accounts, the 64-year-old looks every part the cowboy he grew up watching in Westerns. Almost. Because with few exceptions, TV cowboys did not look like Pete Taylor.

Taylor, who is black, had a “typical” upbringing in Oakland, California. His dad was an executive with the local Boy Scouts chapter, which exposed him to horses as a kid. He found himself drawn to shows such as “Bonanza” and “The Rifleman.” On his bike, he would ride down the bumpy dirt path that split the driveway in front of his house, imagining that the two wheels spinning under him were four galloping hooves.

“I didn’t see them as white or nonblack. I identified with the horses. All I saw was the activity. It just never hit me that I couldn’t do that until I got older,” Taylor said while in Elko last week for the annual National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. He was a speaker helping to highlight this year’s theme, centered on oft-overlooked black cowboys and their impact on the Western frontier.

Historians say roughly one in four cowboys back then was black.

“When we celebrate cowboys, we don’t necessarily celebrate these men, who were the original cowboys,” said Quintard Taylor, a recently retired history professor from the University of Washington, during a lecture at the gathering last week.

Quintard Taylor has studied African American history in the American West for more than four decades.

“Back then it was a matter of record. It was no big deal that there were black cowboys,” he added.

Eventually, the railroad came along, wiping out the traditional cowboy lifestyle. Frontier jobs dried up, pushing most of the cowboys — white, black and Hispanic — into the cities, which offered work and economic prosperity.

But along the way, the cowboys of color would disappear from popular lore, and only their white counterparts became folk heroes.

The westward push

Cowboy culture sprang out of Texas after the Civil War. Men who went off to fight left their ranches and cattle behind. With no one to tend to them, cows got loose — or were let out — across the state.

When the war ended in 1865, returning ranchers needed help rounding them up or collecting fresh, wild cattle.

“A lot of African American men decided to go to Texas because there were thousands of jobs all of a sudden created in the cattle industry,” said Roger Hardaway, a history professor from Northeast Oklahoma State University and author of “African Americans on the Western Frontier.”

For many of them, it was familiar work. As slaves, they tended cattle on ranches in the South.

“We don’t connect African Americans with the cowboy industry. We need to think about the origins of this industry in very, very different ways,” Quintard Taylor said.

Before the Civil War ended, the West and the potential freedoms it promised even appealed to some free African Americans living in the North.

While a plan was being discussed to send free black people to Liberia, an unnamed attendee of the Third Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color in 1833 instead spoke of the opportunities that existed west of the Mississippi.

“To those who may be obliged to exchange a cultivated region for a howling wilderness, we would recommend to retire back into the western wilds and fell the native forests of America, where the ploughshare of prejudice has as yet been unable to penetrate the soil — and where they can dwell in peaceful retirement, under their own vine and under their own fig-tree,” he said, as quoted in an 1833 entry of the Niles’ Weekly Register.

In and around Nevada, African Americans played a prominent role in the settling of the state, despite little recognition for their contributions.

There was Ben Palmer, who was one of the first settlers of the Carson Valley in the 1850s and owned a 320-acre ranch on the western hills of the Sierra Nevada near Mottsville. Newspaper accounts from the mid-1860s to 1870s consistently listed Palmer as one of Douglas County’s largest taxpayers.

There was Dr. W.H.C. Stephenson, who Quintard Taylor said may have been the first black medical doctor west of the Mississippi.

And then there was the case of James Beckwourth. Born a slave around the turn of the 18th century, Beckwourth would become one of the most legendary mountain men in American history. He is credited with discovering Beckwourth Pass in the high Sierra. The town of Beckwourth, located just east of the Nevada-California border, is named after him.

Many of Beckwourth’s exploits as a mountain man are only known because he wrote about them in his autobiography.

“James Beckwourth was very much aware of his place in history,” Quintard Taylor said.

But when “Tomahawk,” the film based on those stories, premiered in 1951, white actor Jack Oakie played the leading role.

“They never had black cowboys in the movies, so you grew up thinking all the cowboys were white because that’s all you ever saw,” said Hardaway.

Henry Harris: Legendary cowboy

In Nevada, there was one black cattle crew boss whose story was unlike any other.

Born in Georgetown, Texas, in the mid-to-late 1860s (the exact year is still debated), Henry Harris started working at a young age for John Sparks, the rancher who would become Nevada’s 10th governor in 1903. When Sparks moved to the Silver State around 1884, he brought the then-teenage Harris with him to work as a house servant.

By that time, Sparks and business partner John Tinnin had amassed a huge ranching empire that sprawled across northeast Nevada and southern Idaho, and it wasn’t long before Harris found himself drawn to working with the horses and cattle, said Les Sweeney, a historian and author of Harris’ biography, published in 2013.

Sparks encouraged Harris to continue working as a cowboy, Sweeney said. Before long, Sparks had named Harris as a foreman over one of his cattle crews. At first, Harris’ crew was made up entirely of black cowboys. But soon, the son of former slaves was overseeing both black and white cowboys and commanding respect everywhere he went.

Harris became revered for his ability to break and train even the toughest and most stubborn horses and, according to Sweeney, always rode the biggest horse himself. He prided himself on his Spanish vaquero style of dress — a classic vest with a silk tie or neckerchief.

“When you rode into Henry’s camp you knew who was boss, you didn’t have to ask,” Sweeney wrote in his book.

Sparks would come to rely heavily on Harris in his operations and handed him the reins to four of his ranches in the area — the HD, Hubbard, Vineyard and Middlestack.

Harris’ reputation grew beyond his job as a cow boss. With his intimate knowledge of the land and the people of the area, he would be called to testify in water rights hearings in Boise. He even helped a Nevada deputy sheriff investigate a shootout between Native Americans and horse wranglers, Sweeney said.

Before long, cowboys from across the West of all races were itching to work for Harris.

“He could do anything and everything better than anybody else. So they wanted to work for him because it was a notch on their spurs just to say, ‘I worked for Henry Harris,’ ” Sweeney told the audience during a presentation on Harris at the poetry festival.

Highlighting contributions

There has been a recent push to highlight the prominence and contributions of black cowboys in a historical sense, according to Hardaway. And much of that can be tied to rapper Lil Nas X and the light that his song “Old Town Road” has helped cast on the often overlooked past of black cowboys.

“He’s kind of lit a fire under a lot of people,” Hardaway said.

But in a contemporary sense, cowboys like Pete Taylor have always existed.

A former firefighter who retired after a significant leg injury on the job, Taylor bought his first horse in 2002 from a stable in the heart of Compton, California.

He is part of an active equestrian group in the Bay Area, a “hidden history” he said he wasn’t even aware of until he was in his 40s. That discovery drove Taylor to learn more about the cowboys he never saw growing up.

“As I studied more history, I found that, well, we’ve always been here,” he said.

But the opportunities that exposed him to horses at a young age are all but gone for many boys like him today. So Taylor sees it as his responsibility to show new generations that there is “something else besides basketball, football, baseball or sports,” he said. And that there indeed were — and are — cowboys of color in the American West.

The sight of him strolling down the street on his horse still comes as a surprise to some, Taylor said, eliciting a common set of questions: “Are you a black cowboy? Is the black rodeo in town?”

But with more awareness and exposure, Taylor hopes those distinctions and questions will fade away.

“Why do we need this description term in front of our names, like black cowboy? He’s just a cowboy. He’s a professional,” he said. “I’m just a guy from Oakland who now cowboys.”

Contact Capital Bureau Chief Colton Lochhead at clochhead@reviewjournal.com. Follow @ColtonLochhead on Twitter.