WINNEMUCCA

A pile of suicide notes written by a young man in 2016 forced District Judge Michael Montero to the realization that rural Humboldt County had a problem it wasn’t addressing.

He remembers reading the notes a sheriff’s deputy handed to him and wondering whether family and friends of the young man could have intervened. Now it was too late.

“The notes were really a young person who was screaming out for help,” Montero said, “and the community missed the signs.”

The death was not an anomaly in this Northern Nevada county, where Winnemucca, with a population of roughly 7,800, is by far the largest town.

Learn what to do if you or a loved one are having thoughts of suicide.

Humboldt, Pershing and Lander counties, which are grouped together by the state in reporting suicides, saw an average of seven people take their lives from 2000 to 2015 before that number mysteriously spiked to 18 in 2016, including six in Humboldt County, state and county data show.

That wasn’t the end of it: Seven people took their lives in the county in a one-month span last fall, with a total of nine dying during the year.

While that was an unusually high number in a short period, it wasn’t a complete outlier. Data from the state Office of Suicide Prevention show that residents of rural Nevada take their lives at a rate 43 percent higher than in mostly urban Clark County and 56 percent higher than in Washoe County.

That, in turn, is reflected across much of rural America, where suicide rates are higher than in urban areas and are growing faster, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

No ‘red flags’

But if the death of the man who wrote the suicide notes was not unusual, it drove home for Montero how few resources the city and county could bring to bear for the mentally anguished.

“The contacts that (those who have died by suicide) had in our community that really should’ve been red flags where we should’ve intervened … it becomes apparent on Monday morning. But why aren’t we identifying that on Sunday evening?”

Montero and other community leaders in Humboldt and adjoining Pershing and Lander counties — among the most sparsely populated counties in the state — have taken different approaches to address the problem.

Winnemucca has a population of about 7,800 and is the county seat for Humboldt County. Suicide rates in rural areas such as Winnemucca, which is two hours east of Reno, are significantly higher than urban areas. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal @rookie__rae)

Winnemucca has a population of about 7,800 and is the county seat for Humboldt County. Suicide rates in rural areas such as Winnemucca, which is two hours east of Reno, are significantly higher than urban areas. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal @rookie__rae)In Humboldt, community leaders launched a public awareness campaign, formed a prevention coalition and brought in experts to train residents on the signs of suicide after the 2016 spike. Pershing County took to the schools to provide mental health resources to students and convince parents of the importance of mental wellness along the way. In Lander County, efforts came later: A local mining company hosted a 5K run to increase awareness of the problem in September 2018 and provided community prevention training this year.

Initially the early efforts seemed to help. In 2017, the three counties saw only one or two suicides — state and county data disagree on the figure.

Leaders “started riding the high,” feeling that they were making a difference, before crashing back to reality, Montero said. Last year the counties reported 13 suicides, including the nine in Humboldt County. That number included the spate of seven in a 30-day period in August and September.

No one has explained the surge, if such an explanation is even possible.

Unexplained and unexamined

Humboldt County Sheriff Mike Allen, who is also the coroner, said an investigation by his office showed none of the deaths was related.

But a state fatality review, which would involve a more in-depth analysis in search of potential connections or commonalities among the victims, has yet to be done nearly nine months after the surge.

Misty Vaughan Allen, suicide prevention coordinator for the state Office of Suicide Prevention, said she has emailed officials at the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office, who expressed interest in discussing a review.

She explained the delay by saying, “We have just been so busy with multiple projects. That’s the only challenge right now.”

Urban-rural divide

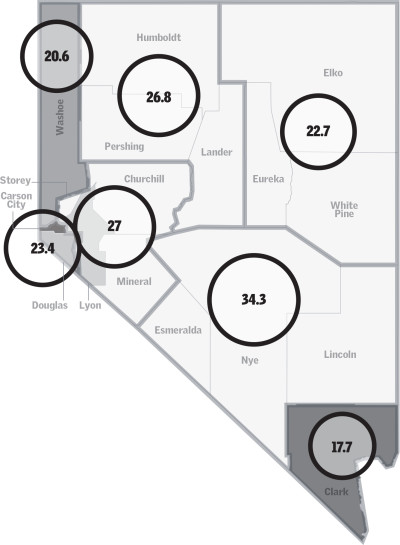

As population density decreases, suicide rates increase. Between 2000 and 2018, average suicide rates ranged from 17.7 per 100,000 in Clark County to 34.3 per 100,000 in a grouping of Nye, Lincoln and Esmeralda counties.

Population density by county per square mile

Average suicides per 100,000 population in region

Legally, such a request would have to come from the state’s Committee to Review Suicide Fatalities, a team of nine including a psychiatrist, hospital representative, law enforcement and the Clark County coroner. It would be a first for the team established in 2013, which typically aggregates randomized suicide data from around the state to identify trends but has never explored an apparent cluster of suicides in one community.

Vaughan Allen, who learned of the suicide surge at a meeting with Humboldt County leaders last fall, said she treads lightly in dealing with rural counties to try to get buy-in before trying the formal approach.

“You want to maintain a relationship working toward prevention,” she said, explaining why her office wouldn’t push to review the rash of suicides unless the sheriff’s office was on board.

“We want everyone to understand the purpose of the review,” she said: to pinpoint trends or a possible cluster of suicides and provide targeted resources based on those findings. “Fatality reviews are not about placing blame.”

Allen, the county sheriff, said he would be happy to take part in a review if it helped his community. Vaughan Allen said she was continuing discussions with the sheriff’s office to try to reach an agreement.

Identifying gaps

Montero didn’t know what to do in 2016 when he read the man’s suicide notes, but he knew he had to do something.

He called the mayor, the county commissioner, Winnemucca’s chief of police and Jennifer Hood, a local marriage and family therapist, and other community leaders together to talk about prevention.

“It was probably one of the easiest things I’ve done in 10 years of being a judge,” Montero said. “Immediately, everyone said, ‘Yes. How can I help? I want to help. Sign me up.’”

Jennifer Hood speaks to April Carlson and her grandson Bentley Brown, 4, as they walk to a park in Winnemucca on April 9, 2019. Brown's parents, though not Carlson, are in the Recovery Out Loud program at the Family Support Center in Winnemucca. Health professionals are hoping that wrap around services and specialty court rulings focusing on recovery will not just heal people but help bring down the suicide rate. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal @rookie__rae)

Jennifer Hood speaks to April Carlson and her grandson Bentley Brown, 4, as they walk to a park in Winnemucca on April 9, 2019. Brown's parents, though not Carlson, are in the Recovery Out Loud program at the Family Support Center in Winnemucca. Health professionals are hoping that wrap around services and specialty court rulings focusing on recovery will not just heal people but help bring down the suicide rate. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal @rookie__rae)That was unusual for a rural community, experts say.

“Out here in the West, we have the mentality of, ‘I can handle this myself. I don’t need anyone to help me,’” said Lynette Vega, who represents the rural north on the Nevada Suicide Prevention Coalition board and is the cofounder of Zero Suicides Elko County.

The grass-roots effort quickly built momentum, beginning with a roundtable discussion on suicide prevention in February 2017. In the months that followed, organizers held a one-day summit open to all community members, created a Zero Suicides initiative to raise awareness in the community and trained law enforcement officers in crisis intervention. They talked about establishing a local 24-hour crisis line, but it hasn’t happened yet.

The effort also called for better education of community members, children and teens included, on signs of suicide and the bolstering of behavioral health services in Humboldt County.

A small group of residents formed the Humboldt Connection Suicide Prevention group, which secured more than $56,000 in state grant funding to create the nonprofit Frontier Community Action Agency and hire a case manager. They also placed a suicide awareness billboard on Interstate 80 heading east into Winnemucca.

The group’s chairwoman, Alaine Nye, said more could always be done, but she’s happy with the progress that has been made. The group is working on a website for Humboldt Connection that lists local crisis resources, using $15,000 in donations from the city, county and local agencies.

Healthier and happier

It’s about 170 miles on I-80 from Winnemucca to Reno, the nearest urban center to the mining town.

“This is Northern Nevada at its finest,” said Jennifer Hood as she merged onto the four-lane interstate on her way to work. The former Las Vegas resident who has lived in Winnemucca on-and-off since 2003 is a therapist and the clinical director for the Family Support Center, one of Winnemucca’s few mental health facilities.

It has a six-week wait list for therapy, but if someone is actively suicidal, providers will get that person help that day, the center’s administrative director said.

But there aren’t enough available services — a common refrain in rural America. There were about 990 Humboldt County residents to every mental health provider in 2018, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s County Health Rankings. The top U.S. performers had a mental health provider for every 310 residents that year.

Hood and her colleagues would love to see more mental health resources in town, especially providers who can prescribe drugs. For now, patients must visit their primary care doctors to get prescriptions that could help with their mental challenges.

There are no psychiatric beds at the local hospital, which is itself an increasing rarity for a rural community. If someone is in crisis and in need of residential treatment, he or she is held in a hospital room designated for the mentally ill until a bed opens at a hospital such as Renown Medical Center in Reno.

Students see their friends getting better. ... The proof is in the pudding because their friends are healthier; their friends are happier.

Shauna Bake, Project AWARE coordinator, Pershing County School District

Still, some experts argue that providing more therapists alone would accomplish little unless you first break down the stigma surrounding therapy and mental health, which tends to be stronger in rural communities.

“It’s no secret that our rurals in Nevada and our Western states are typically more conservative in ideology and lifestyle,” said Steve Nicholas, a Reno-based marriage and family therapist who travels the state providing suicide prevention training to community groups.“If (mental illness) is perceived as weakness, then people do not have an appropriate outlet to treat their mental health condition.”

But transformations in outlook can occur, said Sarah Hannonen, a therapist with Pershing County School District’s Project AWARE program.

In Lovelock, a town of about 1,700 between Reno and Winnemucca, “Our kids are grabbing their parents by the hand and they’re dragging them along” into the realization that mental health is an important piece of overall health, she said.

The project, which stands for Advancing Wellness And Resilience in Education, is funded in Pershing, Humboldt and Douglas counties by a $1.9 million federal grant designed to help rural school districts add mental health resources and increase suicide prevention awareness in whatever ways the community chooses.

In Lovelock, the program enabled the school district to place suicide intervention-trained counselors in schools and create an emotional literacy course for younger students. The children took to it so well that they’ve started peer-led support groups at all grade levels to talk about topics like social anxiety, divorce and teen romance, Hannonen said.

“Students see their friends getting better,” said Shauna Bake, the district’s Project AWARE coordinator. “The proof is in the pudding because their friends are healthier; their friends are happier.”

The Clark County School District provides a similar signs-of-suicide training in eighth grade and high school health classes and has school psychologists on staff, a spokeswoman said.

When funding runs out

But the promising programs the northern counties initiated to address the suicide problem are running out of money as their grants expire.

Project AWARE funding expires in September. And the money for the Frontier Community Action Agency will run dry in September 2020.

While the Pershing County School District’s superintendent has pledged to find money to keep the program running, no source has been identified. The Humboldt County School District will use district funds to pay for five social workers and one therapist to stay in their positions, said Mike Dennis, the Project AWARE coordinator there.

It’s not clear what will come of the project in Douglas County, which took over the program after Lander County surrendered its funding.

In Pershing, school leaders are concerned.

A poster with the signs of suicide posted in the Family Support Center in Winnemucca. While promising prevention programs the counties initiated to address the suicide problem have made progress, they are running out of money as their grants expire. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal @rookie__rae)

A poster with the signs of suicide posted in the Family Support Center in Winnemucca. While promising prevention programs the counties initiated to address the suicide problem have made progress, they are running out of money as their grants expire. (Rachel Aston/Las Vegas Review-Journal @rookie__rae)Shea Murphy, the principal at Pershing County Middle School, said she thought the schools were “doing a pretty good job of handling kids that need to see a counselor here or there” before Project AWARE.

But as awareness increased, children flowed into counselors’ office — Murphy’s son included.

Murphy is trained in suicide intervention because of her work. But on a November morning she and her husband found themselves on the phone with Hannonen, the Project AWARE therapist, asking what they could do to help their teenage son, who was withdrawn and apathetic.

“She’s like, ‘You know what to do. Do it,’” said Murphy, who remembers taking a week off work to spend time with her son, Logan. “I don’t know what we would’ve done if we did not have support here.”

She tries not to think about the alternative, she said.

“I appreciate that we’ve really talked about that mental health is just like any other kind of health,” Murphy said. “You can’t shut that again because that would be unethical. We have students who have needs.”