Iran hostage, family still haunted 35 years later

WASHINGTON — It was late morning and the mob, loud and angry, had pushed its way in through a basement window and was trying to ram in the front door.

Staff Sgt. Mike Moeller and his cadre of 13 U.S. Marine guards were holding off the crowd from entering the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. They were under orders not to shoot. But Moeller, the lead guard, believed the Americans inside would be in imminent danger if the doors were breached.

He spied a ringleader and thought about taking him out.

“Usually it’s not the front guy that’s the leader, it’s the third or fourth one back that’s the rabble-rouser, the one that pushes everyone ahead, gets them worked up. This one individual was standing there doing exactly that,” Moeller said.

“And I said to myself, all I have to do is shoot him in the head, and blood and brains will scatter throughout the crowd. Nobody likes to see their own blood, so it was my interpretation they would probably retreat at that point.”

There was risk, though, of further inciting the mob, elevating a confrontation the United States did not want — and maybe getting all the Americans killed, he thought.

Finally, new orders arrived. The Marines were to fall back and join the rest of the staff in a vault on the second floor in hopes local authorities would arrive and disperse the crowd. Moeller was stunned.

“I simply felt my very spirit, my soul, drop from my body,” he said. “I had just made history as being the only Marine that ever surrendered an embassy. That was harder for me to live with than the solitude” of captivity.

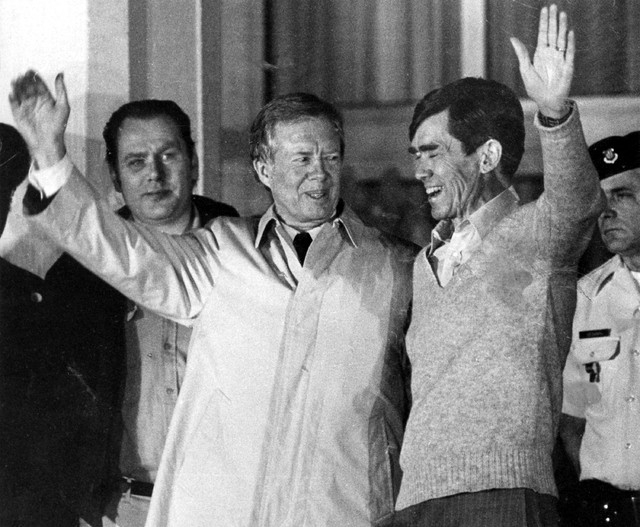

Nov. 4 marks the 35th anniversary of the capture of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and what has been described as America’s first battle with militant Islam. Suspicious the CIA might be working to restore deposed Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a pro-Western autocrat, and eager to dramatize a break in Iran’s ties with the domineering United States, student supporters of the Iranian revolution and anti-American cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini stormed the enclave.

PAINFUL, HAUNTING

Moeller was one of 52 Americans held hostage for 444 days. As Iranians claimed they were being treated as “guests,” the captives were subjected to chain and padlock, long periods of confinement, beatings, threats of bodily harm and execution. They were blindfolded and shuttled among various ministry buildings and prisons. Only in the days before their release were they provided hot and cold running water.

Back home, families lived with stress and uncertainty, and then with the physical and emotional aftereffects when their loved ones returned and their welcome as heroes faded.

Part of the 1979 crisis was recounted in the 2012 Oscar-winning movie “Argo.” The film revived memory of the calamity that had grown dim after confrontations in the intervening years that pitted the United States against radicals around the globe, including the horrific 9/11 attacks.

For Moeller and his family, including his ex-wife and daughters who live in Nevada, the experience changed their lives, some in painful and haunting ways.

The marriage of Mike and Elisa Moeller broke up a year after he returned from captivity. Both remarried, and Moeller later married a third time. Their daughters, who were 4 and 2 when their father was taken hostage, are in their late 30s and live in Sparks, with families of their own.

“It has affected all of us differently, but certainly it has affected all of us immensely, and it has changed our lives forever,” said Elisa Wood, who also lives in Sparks and who kept the name of her second husband after they divorced in 1989.

Wood, 62, suffers from digestive problems and post-traumatic stress she attributes to the experience. At 27, she was the youngest of the hostage spouses and often was called upon to speak for the families during the crisis as well as try to hold her family together including her parents and Moeller’s parents.

A few months into the crisis, the Marines moved her from Missouri to a base in Quantico, Va., outside Washington, after she was targeted by an extortionist who claimed he could put her in touch with her husband.

“I wouldn’t wish this on anybody,” Wood said. “Anytime something happens, whether it is in the Middle East, whether it be … you can name any of them. And especially when they take hostages, it’s like my heart … somebody reaches in and just rips my heart back out. It just kind of rips everything apart inside and it brings everything back to me because I know what they’re doing.

“There are times I have sent messages through various ways to people, saying if anybody wants any conversation, if they need somebody to talk who’s been there … I will talk to them anytime. It’s an experience that no one should have to go through ever.”

EX-HOSTAGE FINALLY TALKS

Moeller lives in his hometown, tiny Loup City, Neb. He doesn’t talk often about his experience and broke his silence in the media through a recent interview with the Las Vegas Review-Journal. He said he is speaking up in hopes it will help the hostages and their families obtain reparations for their suffering in government service.

The hostages were freed Jan. 20, 1981, after the signing of the Algiers Accords, a set of agreements between the United States and Iran to settle the crisis. Among its provisions, the accords effectively barred the captives from suing Iran, and it has frustrated attempts at obtaining compensation for them.

“This has been made difficult because it is unique,” said Tom Lankford, an attorney for the hostages. “These people are the only U.S. citizens who cannot go to the courts when they are tortured by state-sponsored terrorism, bring an action, get a judgment and then execute on that judgment.”

Thirty-nine former hostages are still alive.

Sen. Johnny Isakson, R-Ga., introduced legislation that would grant compensation to each and to the estates of the 14 who have died including Richard Queen, a 53rd hostage who was released after 250 days when he began suffering from symptoms of multiple sclerosis.

The $233.2 million bill would give the hostages $4.4 million apiece, or $10,000 for each day they were held. Their attorneys say that is the standard measure applied by the courts and the government in hostage situations. The money would come from fines and penalties levied on individuals and companies that have done business with Iran in violation of U.S. sanctions.

Five years after their release, the hostages received about $22,000 apiece from the government, or about $50 in per diem for each day they were held captive.

Attorneys for the hostage families are seeking amendments that would compensate spouses and children of the captives by half the $10,000 daily stipend.

Lankford said the judge who heard a 2001 lawsuit filed by the hostages opined “the families in this instance, because of the coverage and because of the way Iran was manipulating and trying to reach out through the media to build fear in the hostages and their families, that they were harmed every bit as much.”

Moeller rejoined the Marines after he returned from Iran, and retired from the military in 1991. He moved to Loup City, opened a cleaning business and became an antiques dealer. Now 63, he is retired, collects currency and still dabbles in antiques.

WHAT WAS DONE TO THEM

Moeller said captivity changed him in myriad ways, some “I can’t begin to explain.”

He said he has very short memory retention, a short temper and has trouble completing tasks. His stress symptoms elevate “especially as anniversary dates approach.” He said there are times he cannot leave the house, and he has to tell himself it’s OK to go outside without seeking permission.

In Iran, Moeller was a strapping 6-foot-4. He said his physical presence did not spare him from being pushed over chairs and thrown around while handcuffed and blindfolded, and being tormented in other ways.

“Part of the Iranians’ amusement was to hold onto our arms and at some appropriate moment swing us to the left and to the right, into a wall as hard as they could,” he said. “Now, with your hands cuffed behind your back, you’re not going to catch yourself so you had head injuries, shoulders that were perhaps broken but certainly bruised and pushed out of sockets.”

One night three months into captivity, Moeller and about half the hostages were awakened, blindfolded and herded into a room. They were put up against a wall and told to raise their hands. Blindfolds removed, they faced a dozen masked men with rifles pointed at them while the Iranian chief of security barked orders and the executioners loaded their weapons.

Some of the hostages began to shake. Some prayed and recited Psalms.

The chief yelled, “Fire!” Nothing happened. The men in the masks laughed.

Moeller had a dim view of his captors, who he said weren’t good around guns. “It just scared me to death that by screwing around with those weapons, loading and unloading them, they would accidentally shoot me. They didn’t have any training per se, except to load and fire.”

Moeller took to flinging verbal abuse at the Iranian guards, according to author Mark Bowden in “Guests of the Ayatollah,” his book about the hostage crisis.

Moeller began substituting the word “Khomeini” for “every foul word in the English language, and his fellow Marines adopted it with relish,” Bowden wrote. “When they needed to use the toilet, they would tell the guard, ‘I need to take a Khomeini.’ ”

While Iran was holding the Americans, it also was preparing for war against Iraq. Moeller remembered an Iraqi infiltrator who was captured and tortured twice a day, his screams echoing in the cells.

“You could hear him,” Moeller said. “As soon as he heard footsteps he was screaming, crying, just begging for help, and then the doors opened and it was even louder, and they would drag him down the hall. You’d hear them torture him for several hours.

“You’d find yourself praying, and you don’t know if you’re actually praying for him to die so he can stop suffering or praying for him to die so you will stop hearing it,” he said. “They did kill him. They shot him midscream, and it was over.”

Moeller spent nine months off and on in a warehouse basement with cellmate Paul Needham, an Air Force captain from Bellevue, Neb. They began planning an escape.

“We had found a map and thought we had it planned out pretty well,” Moeller said. “We started exercising, twice a day every day. We didn’t have shoes so we did it barefoot. I’d guess we exercised between four to six hours every day. We’d start out by doing a hundred pushups, then we’d get up and do a hundred jumping jacks and get down and do another hundred pushups.”

But the captors somehow discovered the plan and moved Moeller and other plotters to another prison. Today, Moeller remembers the hours upon hours of exercising with bare feet on concrete when he aches from deterioration of two vertebrae in his lower back.

“I’ve had both hips replaced,” he said. “Both knees should be replaced, but that won’t be until I fall down.”

What Moeller said he feels most of all is guilt.

“Absolutely,” he said. “I was guilty of letting down my country, my Corps, my Marines. I just took ownership of the entire thing.”

Moeller believes Iran’s success in holding off the United States for 444 days was a foreshadowing of a world where America is less respected and more vulnerable.

“As I say, I’ve taken ownership for everything that’s gone on so far in the world, from Desert Storm on,” Moeller said. “The fact we were a superpower that allowed the Iranians to take us and hold us in a position for 444 days, and President Carter basically was forced to sign an illegitimate agreement just to get us out.

“And because of that, they felt they knew how to deal with the United States of America. They knew they could beat us,” Moeller said. “There are going to be people going to tell me I’m crazy but I don’t believe so and I don’t think a majority of Americans believe so either.”

Contact Stephens Washington Bureau Chief Steve Tetreault at stetreault@stephensmedia.com or 202-783-1760. Find him on Twitter: @STetreaultDC.