Deserted Datsun near Las Vegas helps man cope with loss

The white 1980 Datsun sat with its rear deep in the sand, hood up, teetering on a crevice.

It didn’t look like much, the shell of a B310 left baking in the Mojave Desert sun for more than two decades.

But to one Wisconsin man, the car is a connection to the father he knew next to nothing about for most of his life.

Michael Blackburn first heard the story in 2012, when he reconnected with his sister. A report filed with the Mohave County Sheriff’s Office detailed the scene from 1997.

The morning Mark Blackburn’s body was found, National Park Service ranger Mark Burt spotted the white 1980 Datsun B310 first.

Feet away, he saw the body: The damaged tissue on his right hand. The singed mustache, the gaping wound above his left eye, the tiny holes in his blood-stained shirt.

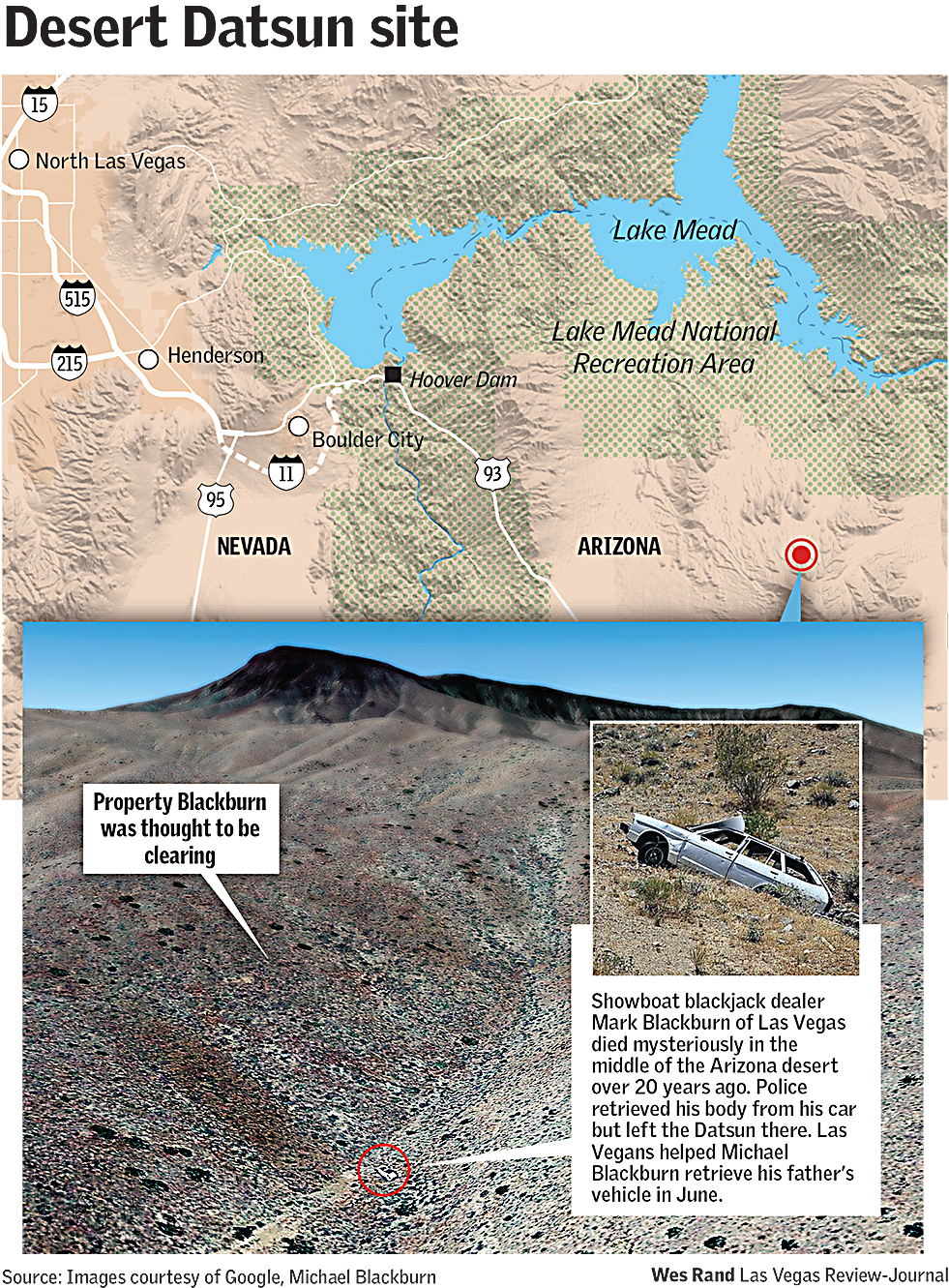

The Las Vegas blackjack dealer died alone, in the empty stretch of Arizona desert. He had been missing from work at the Showboat for a few days before he was found July 23, 1997, in Mohave County, outside the Temple Bar section of Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

His injuries appeared to stem from a homemade explosive device, and his death was determined to be accidental, the sheriff’s office report said. The Datsun remained at the scene.

That is, until last month, when complete strangers from The Wrenching Network — a Facebook group of more than 27,000 mechanics — set out to recover it.

Starting with the help of generous Las Vegans, Mark Blackburn’s son, Michael, and his daughter, Lalani Blackburn-Bill, recovered the car from the depths of the desert.

Pulling it out of the desert

The Mojave Desert in June is brutal, its terrain unforgiving. David Nehrbass, 47, knew that quite well.

The burly, 6-foot-3 man smiled through the gap in his front teeth. He equipped himself and four others with two large Ford F-350s, four-wheel drives ready enough for a trip 50 miles off road.

Now they were picking up the trailer that would tow the car to town.

“It takes a half a million dollars in equipment to pull out something worth $20 in scraps,” he joked. “Yes, we’re out of our minds.”

Nehrbass is a public safety dispatcher for Lake Mead National Recreation Area, not far from where Mark Blackburn died. He learned about the Datsun through a GoFundMe account, which had raised $1,691 as of Sunday.

A man he had never met, Michael Blackburn, had been separated from his birth parents when he was a small child, and was adopted into a new family. After reconnecting with his sister, he and Blackburn-Bill learned that their dad’s car was still out there.

He figured out where the coordinates were, and in 2012, he and his wife, Kerilyn, got caught in a wash on their way there.

“I’m gonna get my dad’s car out of the desert,” he told people on Facebook, through The Wrenching Network. “One of these days, I’ll get back there.”

A Mercedes-Benz technician from Alabama, George Soutar, started the movement by soliciting members in the Las Vegas area to help Michael Blackburn recover his dad’s old Datsun.

Nehrbass knew his 0ff-road, rescue, medical and recovery service business, Motorsports Safety Solutions, was in a unique position to help.

He and his co-workers had seen the car perched on the crevice and towed it a mile down onto flat land.

CLICK TO ENLARGE

The fact that the two-wheel drive with donut tires had made it out there was in itself a miracle, Nehrbass said.

“It’s going to be kind of emotional to see this thing back in town,” he said as he followed behind his co-worker. “It’s been part of the landscape for 20 years.”

After getting it into town, a “relay tow” of seven people, organized by Las Vegan Lonny Burgess, would ensue. The siblings would hop on the road trip to Hartford, Wisconsin, where Michael Blackburn lives. The 37-year-old mechanic planned to fully restore it.

Another local, Melissa Phillips, provided the trailer for the journey. She’d be the first member of The Wrenching Network to help tow it.

In the desert, Nehrbass’ pickup bounced and swayed. The dry pollen-ridden Yucca bushes scraped at its doors and windows.

“There, that’s a memorial,” he said of the car they were seeking.

Sure, the Datsun had been home to pack rats and smelled like a port-a-potty, but the odometer showed 146,000 miles, and the car hadn’t rusted, he noted.

He cruised at a steady 13 mph, past an abandoned boat, discarded tires, beer bottles from the 1990s.

On first glance at the car, the crew pointed out the bullet holes on the right rear door, seemingly from when the explosive — a pipe with powder from 12-gauge shotgun shells — exploded as Mark Blackburn screwed on the detonator cap.

In about 20 minutes, they had used both trucks to shackle and winch the car. The shredded and rotting tires screeched onto the trailer.

Nehrbass and the four others in neon shirts signed their names on the left fender.

A broken family

Michael Blackburn was 3 when he was separated from his parents, who were then living in California. His sister was 6.

Documents with the California Department of Children’s Services say that sexual abuse occurred involving at least one of the children. The siblings say they experienced abuse in their childhood, but that it wasn’t at the hands of their father. Because there was no court order stating who was supposed to have the children, Michael Blackburn and Blackburn-Bill were forced to go to foster care until it was sorted out.

It never was.

“My dad was just grasping for straws,” said Blackburn-Bill, now 40. “My father was a survivor like the rest of us, he did the best he could with what he had. He did everything that they asked him to do to get us back.”

At first, the kids had weekly visits with Mark Blackburn, a man with a military-style mustache, chubby cheeks, green eyes and dark hair. But those ended soon after.

“He wanted to have us as kids, but he didn’t have the income,” Blackburn-Bill said. “Back in the day, the rules were different, and fathers didn’t have rights.”

Michael Blackburn was eventually adopted at age 10. While living with his new parents, he said, “I wasn’t given any opportunity to contact my family.”

No memorial

Despite not being able to parent his children, Mark Blackburn was always there for his daughter, who was in and out of foster homes until she was 16, Blackburn-Bill said.

She learned to drive in his white Datsun.

When her grandmother died, she and her dad took the car from Las Vegas to Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego, where they poured her ashes in an unmarked grave next to one of her other sons, Gary.

He made his daughter promise that when her brother found her, she would tell him where their grandmother was.

“I kept that promise,” Blackburn-Bill said.

When her dad died, he had no funeral, no memorial, no headstone. She buried his ashes next to the same grave at Fort Rosecrans.

A memorial, 21 years later

Mark Blackburn told Blackburn-Bill that he was clearing the land on the property he was renting to own, a section of land for developing known as Mead-O-Rama.

She said she believes that’s why he was out there with an explosive device, removing Joshua trees in anticipation of building a home.

At the time, he lived in a single-wide trailer at the Oasis Mobile Home Park. This would have been his first real house.

“That’s probably the silver lining in this entire thing,” his daughter said. “He died where he wanted to live.”

On an arid, triple-digit day in mid-June, Blackburn-Bill and her brother stood at the site where their father died.

Nehrbass poured cement into the ground and erected a makeshift headstone, a steel memorial that stood about 3 feet high. Cut into it, a black and white sketch of the Datsun.

It read: “In memory of Mark Blackburn. 7-97.”

“Oh my,” Michael Blackburn said when the sign was unveiled. The warm air whipped his face like a blow dryer.

He rested his head on the sign.

“He died alone in the desert,” he said. “And I wasn’t there with them.”

He’d agreed to be adopted, he explained. He said he feels partially responsible for the turmoil.

Looking around for any sign of her father, Blackburn-Bill recognized the trash can lid on the ground. That was dad’s. Her brother got on his hands and knees, searching for the pieces of the glass from the car’s head and tail lights.

Halfway buried in the sand, Blackburn-Bill found a shotgun shell, still intact from the explosion. Tears welled in her eyes. She put it in her pocket.

“It was almost a homecoming, but it was heartbreaking at the same time, because you knew somebody was missing,” she said later. “It just reminded me there’s a hole.”

She felt her dad there, and pictured his “damn mustache,” his Bart Simpson impersonations, his love for air hockey and drive-in movies.

Before he died, Mark Blackburn had put three green stakes in the ground. That day, his kids left them behind.

They saw the stakes as a symbol of a man with his two children, standing a few feet away from each other. Together.

Contact Briana Erickson at berickson@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-5244. Follow @brianarerick on Twitter.