Bunkerville rancher vows to resist federal roundup of his cattle

This is not Cliven Bundy’s first rodeo, but will it be his last?

For the second time since 2012, the Clark County rancher has been served notice by federal authorities who plan to impound hundreds of cattle he left to roam on public land almost 20 years after the government told him to remove them.

The Bureau of Land Management’s impound notice took effect Monday and lasts until March 23, 2015. The agency expects to announce details of the proposed roundup today.

In an email to the Review-Journal, Kirsten Cannon, spokeswoman for the bureau in Southern Nevada, said the “illegal trespass cattle” can now be gathered “without further notice” from BLM and National Park Service land in the Gold Butte range, about 80 miles northeast of Las Vegas.

“Tell them Bundy’s ready,” the rancher said by phone Tuesday from his home near Bunkerville. “Whenever they’ve got the guts to try it, tell them to come.”

The last time federal authorities laid plans to remove Bundy’s rogue livestock, in April 2012, it ended with veiled threats of violence and a hastily canceled roundup.

Since then, two more federal court rulings have been handed down against the rancher, including one by U.S. District Judge Larry Hicks in October that ordered Bundy not to “physically interfere with any seizure or impoundment operation.”

“BLM and NPS have made repeated attempts to resolve this matter administratively and judicially. Neither the court orders nor agency communications have gained the voluntary removal of the trespass cattle from federal lands,” Cannon said. “We are working with our partners to coordinate the impoundment in a manner that is safe for the public, our employees and the cattle.”

Bundy’s dispute with government dates to 1993, when his herd on the federally managed, 158,666-acre Bunkerville allotment was capped at 150 animals out of concern for the federally protected desert tortoise.

To protest the change, the rancher stopped paying his monthly grazing fees of about $2 per head but kept using the allotment, which included more than 10,486 acres of National Park Service land at the northern end of Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

“Why should I pay BLM to manage me out of business?” Bundy said Tuesday. “What I did is I fired the BLM.”

In response, the bureau canceled Bundy’s grazing permit in 1994, but his livestock kept on living off the public land his family has used since 1877.

In 1998, a federal court ordered him to remove his animals, but the cattle remained and grazing continued. The following year, federal authorities officially closed the Bunkerville allotment to cattle to protect tortoise habitat, but no effort was made to remove livestock already there.

Rounding up Bundy’s animals now will be no easy task.

The bureau’s most recent count, conducted by helicopter in December, logged 568 cattle scattered across a 90-mile swath of federal land in the Gold Butte area.

The numbers have been much higher in previous counts. A March 2011 aerial survey tallied 903 animals, more than 300 of which were found in remote, roadless areas the bureau said could not be accessed by teams on the ground.

At least a third of the cattle loose on the range may be unmarked descendants of Bundy’s branded herd, but the rancher also claims those animals. If they’re found within or even near his herd and they don’t bear someone else’s brand, he figures they must belong to him.

“I will claim all of those no-brand cattle as private property,” he said.

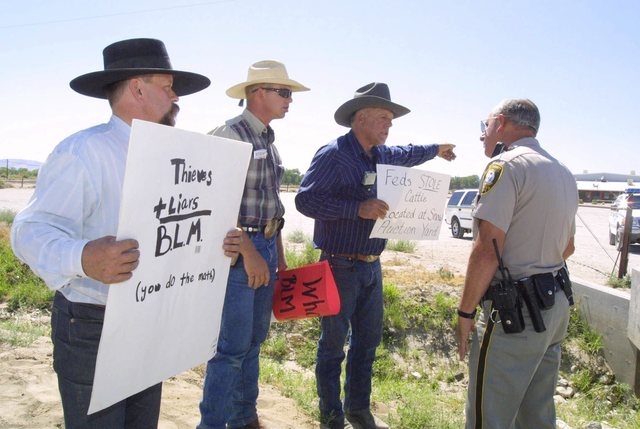

Since he received the impound notice last week, Bundy has been sending out letters declaring a “range war emergency” and demanding protection from state and local officials. He said all it would take to bring the federal roundup to a halt is for Clark County Sheriff Doug Gillespie to say no, or for state brand inspectors to refuse to transfer ownership of his cattle to the government.

As he did in 2012, Bundy is also sending letters threatening legal action against contract cowboys the government might hire for its roundup, which he considers “cattle rustling.”

“I’m protecting my rights as a rancher, and I’m also protecting the rights of all Clark County residents to access and policing power over this land,” he said.

The dispute is being watched closely by conservationists interested in seeing the Gold Butte area protected, perhaps as a national monument.

Rob Mrowka is a senior scientist with the Center for Biological Diversity, a Tucson, Ariz.-based environmental group that has threatened to sue federal authorities for failing to remove Bundy’s livestock.

“This situation is simply outrageous,” Mrowka said. “It’s high time for the BLM to do its job and give the tortoises and the Gold Butte area the protection they need and are legally entitled to. As the tortoises emerge from their winter sleep, they are finding their much-needed food consumed by cattle.”

If and when the cattle are rounded up, Bundy will be allowed to claim any that bear his brand, so long as he pays the impound costs and trespass fees assessed by the government.

Through Sept. 20, 2011, Bundy has been billed $292,601.50 in trespass and administrative fees, Cannon said. His balance since then is currently being calculated.

Bundy said if his cattle are rounded up and eventually returned to him, he will see to it that they end up right back where they were in the first place.

“I’m going to turn them back out and raise some more beef for people to eat,” he said.

Right now, though, Bundy is concentrating on trying to keep the roundup from happening at all — peacefully, if he can.

“I’ll do whatever it takes,” the rancher said. “They’re not going to get a hair of my cattle or any of my property.”

Contact reporter Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow him on Twitter @RefriedBrean.