Activists lobby to save Clark County petroglyphs from dam silt

Conservation advocates are sick of all the silt, and they’re calling on the Bureau of Land Management to fix the dam problem.

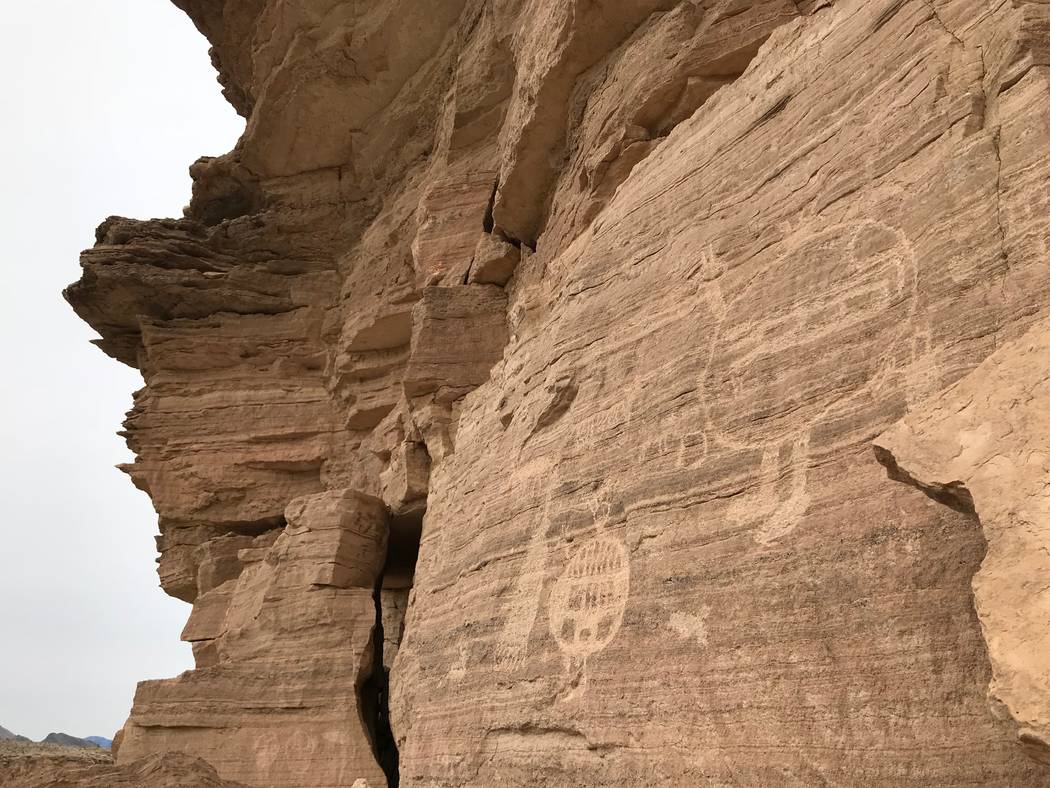

A small group of longtime conservation activists is urging the federal agency to address issues with a historic dam 65 miles northeast of Las Vegas that is trapping mud and slowly burying petroglyphs and other cultural resources in the Arrow Canyon Wilderness.

“If we don’t do something now, all of that stuff you saw in the wash will be gone,” Terri Robertson said Tuesday after a tour of the remote canyon.

Robertson is well-known in the conservation community for the decades she spent lobbying for the protection of such places as Red Rock, Sloan Canyon and Gold Butte. Now she is the organizer — some jokingly say instigator — of the newly formed Upper Arrow Canyon Management Committee.

The group basically consists of Roberston and fellow rock-art protectors Cherry Baker, Elaine Holmes and Anne McConnell, but they are recruiting additional allies. That was the purpose of last week’s tour: to win over representatives of other conservation groups by showing them some of the canyon’s treasures and what is happening to them.

Late in their hike through the canyon in northern Clark County, Holmes led the group to a site known as Altar Rock, an angled slab the size of a garage door that was edged with saw-tooth notches and covered in symbols by ancient hands. She said there is an old photograph from the 1940s showing a man on horseback with Altar Rock towering above him. Today the silt reaches so high that you can stand next to Altar Rock and easily peer over the top.

“You don’t know how many archaeological sites are buried under that silt,” Holmes said.

The Civilian Conservation Corps built Arrow Canyon Dam during the Great Depression to control flood waters in Pahranagat Wash. The BLM now owns the stone masonry structure, which qualifies for listing on the National Register of Historic Places but still serves its original purpose.

“The Arrow Canyon Dam continues to protect 740 square miles, including Moapa tribal lands and public and private lands along the Muddy River,” BLM spokeswoman Kirsten Cannon said in an email. “As such, our top priority is to keep the dam functioning.”

Funding being sought

Robertson and company aren’t trying to get the dam taken down, but they would like to see it better maintained. They also want the BLM to remove decades worth of silt that has accumulated behind the structure, covering some of the rock art etched into canyon walls and providing a foothold for invasive tamarisk plants.

Robertson said scraping away the silt and eradicating the thick grove of tamarisk now choking the canyon “might take 15 years,” so its important to get started before the problem gets even worse.

“We want to see the things we lost,” she said. “We want to see what’s being buried by all that silt.”

Cannon said the BLM is aware of Robertson’s concerns and plans to apply for money through the Southern Nevada Public Land Management Act to study the matter further.

“We greatly appreciate all Terri has done for public lands and have told her that we will evaluate impacts to petroglyphs when funding is secured,” Cannon said. “Terri’s proposal would require determining if silt removal would alter the structural integrity of the dam.”

She added that “cultural resources within the silt itself would need be taken into consideration” before any large-scale excavation takes place, referring to the possibility that buried artifacts could be destroyed during silt removal.

Consulting ‘the ancient ones’

Local tribal representatives would like to be included in whatever the BLM decides to do.

Tyler Samson grew up on the Moapa River Indian Reservation and now serves as vice chairman of the Moapa Band of Paiutes. He said Arrow Canyon is a sacred place for the Southern Paiutes and those who came before them.

“That place is for gathering medicine, visions and ceremony, has been since prehistoric times,” he said. “It’s just thick with the ancient ones.”

Samson said it would be nice to see the area cleaned up and “reclaimed.” But what he’d really like is for the BLM to consult the affected tribes and directly involve them in both the planning and the execution of the work.

“Everybody means well … but the tribe should have a bigger part in what ultimately happens there,” he said. “It’s so close to us, but we still feel like we can’t protect it.”

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean @reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.