UNLV cadets teach, learn in foreign lands

They went to some places in the world where American soldiers are seldom seen, where Kirundi and Swahili are spoken more than English, where the way of life is much different than the University of Nevada, Las Vegas campus where they walk around in camouflaged uniforms that student ROTC cadets wear to become Army officers.

One trained with military counterparts in Greece and scaled Mount Olympus.

Another taught English to aspiring armed forces cadets in their native Thailand.

Two went to the island nation of Cape Verde, off the coast of west Africa.

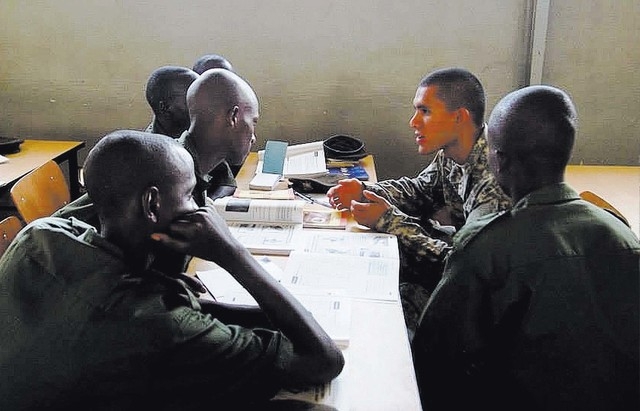

And the fifth, Timothy McMoore-Tuamoheloa, completed his cultural understanding mission in Burundi, a landlocked country in southeast Africa bordered by Rwanda, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“When I first arrived, I was like, ‘Whoa. I’m in Africa.’ It was different than what I’m used to,” he said. “Their airport was very tiny. There’s one gate, one airplane.”

McMoore-Tuamoheloa, 19, of American Samoa, taught English to Burundi’s defense specialists who defend the country from surrounding nations and groups within it who were involved in a civil war.

“They’re still trying to rebuild their nation,” he said. “A lot of it was run down or destroyed.”

The people of Burundi primarily speak Kirundi but also French and Swahili. “I learned a little bit of Kirundi, the basics,” he said.

McMoore-Tuamoheloa said his experience will prove to be valuable for future deployments, particularly to Africa. “It will help me learn about different cultures as well as build relationships with future officers because the people I was training with are about my age, and they’ll be pretty much the same rank.”

He said his counterparts in Burundi perceive America as “the ultimate place to go to. They see us as the figure they want to be or the point they want to get to when they advance in their military. Every single one of the cadets we spoke to wanted to go to America because they wanted to better their lives and have better opportunities.”

Andrew Flannigan’s mission was not to teach English but to train with the Greek military and to learn how to work with NATO allies.

“It was definitely a culture shock,” he said. “You get on the ground there, and they treat you like their own cadets. It was a very different experience. … The Greeks, they give you two canteens for a day. If you drink them, you drink them. You’re done.”

“They put on face paint for everything. Even to go get food, they put on face paint,” he said.

Flannigan, 20, from Oxnard, Calif., said he participated in mountain warfare training and “a lot of amphibious work … a lot of close-quarters combat and a lot of stuff with grenades. They love grenades,” he said, noting, “The Greeks have a huge focus on beach defense.”

The training took place at the base of Mount Olympus. “We actually got to climb Mount Olympus. It was more like woods. You couldn’t see anything, like a forest on a mountain,” he said about the 9,573-foot mountain famous in ancient Greek mythology.

Christopher Coffey, 21, of Redlands, Calif., who is starting his third year in the UNLV ROTC program, taught English at Thailand’s Armed Forces Academy Preparatory School.

He said the experience will help him adjust later in his career if he has to interact with foreigners in countries at the center of conflicts such as Iraq or Afghanistan.

Coffey was impressed with how much English pre-cadets at the academy already knew.

“It pretty much blew my expectations. … Most of them had a decent understanding of English. The underclassmen knew more English than the upperclassmen,” he said.

Jacob Pestana, 27, an Iraq War veteran from San Bernardino, Calif., spent most of July and part of August in Cape Verde teaching English to cadets and officers from Cape Verde’s military that numbers only 800 troops. They speak various dialects of Portuguese-Creole.

“We had three of the only six aviators that exist in their military. So we literally had half of their aviation branch in my cadet class, which is cool because they only have one aircraft,” he said, describing a single-engine aircraft “a little bit bigger than a Cessna.”

Pestana, who deployed to Iraq in 2008 as a 28th Infantry Division cavalry scout with the Pennsylvania National Guard, said Cape Verde’s military is tasked with policing and deterring piracy and trafficking. “Their two biggest things on the islands are trafficking of humans and drugs.”

Patrolling the waters is done with one ship and one aircraft. Cape Verde’s military police force maintains security at public events and festivals. “It’s not like in the U.S. where you have policemen doing that. They have their military out in force at all major events.”

Pestana found out that English, for the most part, is understood by the islanders of Cape Verde because “they pick it up from pop culture. I’ll tell you, it’s pretty pervasive. They speak a lot of English.”

Among the benefits of his experience that will advance his military career, Pestana said it will help lessen the culture shock on getting deployed to a country like Afghanistan.

“You get your first rodeo out of the way, basically,” he said. “So maybe the next time when you’re actually leading troops in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language, you’ll have a little bit more experience and be a little bit more calm.”

Cadet Matthew Orlina, 23, of Camarillo, Calif., was also at Cape Verde but he went to a different island than Pestana, who was at Mindelo on the island of Sao Vicente.

Orlina, an Army Reserve civil affairs specialist, taught English to 33 Cape Verde army soldiers and one civilian in Praia, the capital and largest city of Cape Verde on the island of Santiago, 500 miles west of Sierra Leone

“They’re really interested in our cultural differences,” he said. “They have an interesting animal problem. They have dogs just wandering around. They’ll take a pup and raise it until it’s not cute anymore and just let it go.

“They have no animal control. They also have no recycling or trash program. If you go into the rural areas of the island, you’ll see people farming and in the middle of field, they’ll just be burning their trash because they have no way to dispose of it,” Orlina said.

Among the things he learned from teaching English is that Americans, unknowingly, take the language for granted.

“You would say something, and they would ask, “Why do you say it that way?’ It doesn’t have to be a colloquialism or an idiom, it’s just the way everybody talks. Why do I say it that way?” he said.

Orlina said he came back knowing that “people can live differently and we can still be happy.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Follow @KeithRogers2 on Twitter.