Those who enter police academy out of shape find out fast they don’t belong

The clock has yet to strike 7 a.m. as Sgt. Dan Zehnder makes his way through the halls of the Metropolitan Police Department Academy.

The newest class, Class 6-09, is back for Day Two of the six-month academy. After the wake-up call on Day One, the recruits have had a three-day weekend to rethink their decision to join what Zehnder calls the toughest all-around police academy in the nation.

Zehnder stops by the offices of the academy’s Training and Counseling, TAC, officers, looking for Dean Leslie, the man in charge of the class.

Leslie isn’t there, but fellow TAC officer Jonathan Simon is. Zehnder asks if anyone has resigned.

"No quitters," Simon says.

Zehnder clutches his chest and wobbles.

"Is Dean losing his touch?" he says with a smile.

All 27 recruits remain — for now.

The recruits start Day Two completing various exercise tests mandated by the state’s Commission on Peace Officers Standards and Training.

The tests include a vertical jump, push-ups, sit-ups, a 300-meter sprint and a 1.5-mile run.

Recruit Sean Barrett, a 41-year-old retired airman who labored through the exercises on Day One, is struggling again.

He completes 26 push-ups, just two over the minimum. He finishes the sprint in 74 seconds, barely beating the 77-second time limit.

"Seventy-four. Way to be prepared. You’re ready for this. … Way to be prepared, Mr. Barrett," TAC officer John Liles says.

"That wasn’t a freaking compliment," he adds, as if he needed to.

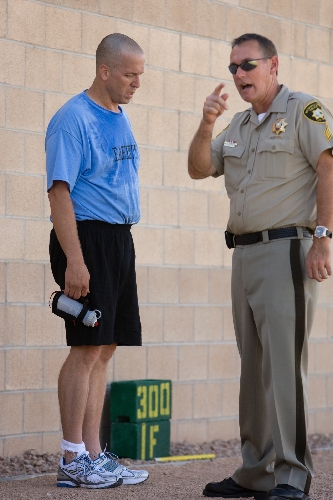

Minutes later, Leslie breaks the news to Zehnder.

"He’s resigning," he says. "He doesn’t want to deal with us red-dogging him."

At 7:35 a.m. on Day Two, Barrett becomes the first casualty of Class 6-09.

Zehnder tells the class.

"Well, we’ve already lost one," he says matter-of-factly. "Mr. Barrett is now gone. Quite frankly, that’s a good thing. He wasn’t physically prepared for the academy, and he’s not the only one."

That’s all too common at the police academy, Zehnder said.

Many recruits are out of shape when they arrive despite passing the initial physical fitness test to get hired.

Some recruits train throughout the hiring process, which can take months, but many wait until they are officially hired before training hard.

That might give them just six weeks or less to burn off years of junk food and couch surfing.

Zehnder and his academy staff push the recruits to their physical limits for good reason. On the street, they might have to chase after criminals, jump walls to help fellow officers, maybe even survive a knockdown, drag-out fight for their lives. They can’t afford not to be in shape.

The strenuous exercise also tests the recruits’ mentality. When their muscles burn and ache with each repetition, do they give up or press through the pain to finish?

"I’ve got 94 days to turn you into something that resembles a police officer," Zehnder says to no one in particular. "This is what will keep you safe. You just don’t know it yet, or you’ll know it the first time you’re getting your ass kicked."

Class 6-09 is now in the midst of a grueling back-and-forth workout on the academy field, which stretches about half a football field long.

The recruits are doing crab crawls, walking backward on their hands and feet across the grass with their water bottles clenched between their teeth.

Halfway across the field, recruit Garrett Forni stops with a cramp.

"Take a load off," Zehnder says with his trademark disgust, exiling Forni to the shade of a nearby wall. "You gave up, Mr. Forni. How does it feel to be a quitter?"

Zehnder stops glaring at Forni just in time to see Yilikal Merha drop to the grass. Zehnder orders him to join Forni.

Meanwhile, Heath Smith, whom Zehnder sent to the shade for giving up during an earlier exercise, struggles through the crab crawl and crosses the finish line. He’s last, but he finished.

"Hey, you two knuckleheads, this is not quitting," Zehnder tells Forni and Merha. "He shouldn’t be proud of it, but he didn’t quit."

Zehnder then rounds up the recruits and stands them in a half circle around Forni and Merha, who are sitting in the shade with their backs against the wall.

"Repeat after me," Zehnder says. "Quitters."

"Quitters," the class responds in unison.

"Quitters."

"Quitters."

Ten times they repeat the word before reassembling on the field. Zehnder sends Forni and Merha back to the group with a message.

"I suggest you don’t quit again, or we’re going to have a problem," he says.

Back in the classroom, Zehnder goes into teaching mode for a lesson in police values and ethics.

He reminds them that police officers are held to a higher standard, on and off duty.

A couple of photos flash on the projection screen of a young man at a shooting range. One of the captions reads, "Popin’ some punkass bloods."

That man had been hired to start the police academy recently when he posted the photos on his MySpace social networking website.

Imagine, Zehnder tells the class, if that recruit made it to the streets and shot someone in a black neighborhood. Two days later, those photos would be all over the television and on the front page of the newspaper.

"For us, this would be a Rodney King," he says.

The recruit was fired before he started the academy.

Zehnder tells them how the bad actions of wayward officers, such as when two off-duty Las Vegas cops got drunk and killed a gang member in a drive-by shooting in 1996, taint everyone wearing the badge.

"That’s why when one of you screws up, we punish you all," he says.

He reminds them that their integrity must be maintained.

That’s why it’s the first word in the Police Department’s values acronym: ICARE, which stands for integrity, courage, accountability, respect for people and excellence.

If they slip up, defense lawyers will attack their integrity and honesty any chance they get. They would never be able to testify in court again, he says.

"They will always go after your lack of integrity. You’re done. You’ll be pushing a desk at the airport," Zehnder says.

For Zehnder, Day Five of the academy is one of the most important.

Today the recruits will be exposed to the reality of police work and the worst the job has to offer. Gunfights with bad guys. Taking someone’s life. Long-term stress on the body. Depression. Divorce. Suicide.

They’ll need to know what lies ahead and decide whether they are truly prepared to be police officers.

But first, more yelling.

The recruits stand in formation on the grass field and squint into the rising sun, wearing tan uniforms, ball caps and utility belts, with handcuffs, guns and other equipment.

Eugene Yanga, the appointed class leader, stands alone in front of them.

At 7 sharp, six officers wearing their dress uniforms emerge from the academy building and slowly march to the field.

First inspection is about to begin.

Leslie rips off Yanga’s hat, throws it to the ground and screams in his face.

The other officers join in, taking their own bite or two as the feeding frenzy begins.

"Straighten that hat, Chapman!"

"Your hands straight down the seams of your freaking pants!"

Zehnder and Leslie stroll the ranks, moving slowly from one recruit to the next, berating them, quizzing them, stressing them, challenging them, pushing their buttons.

Predictably, Zehnder doesn’t like what he sees.

"Officer Leslie, clean this mess up," he says.

Push-ups and shoulder presses follow.

They redraw their guns, and Forni drops his to the ground. Leslie tosses it in a box.

"Are you freaking going to start crying, Forni?"

Silence.

Simon jumps in.

"You’re not going to make it, Forni!" he screams inches from his face.

The officers take a few more bites and swim away.

In 10 more minutes, they’ll be back.

The recruits collect themselves, dust each other off, get their ranks in order.

The officers soon return, and Forni’s fresh blood draws them in.

Officer John Liles steps into him and asks why he wants to be a police officer.

"I want to make the community a better place," he replies.

"The community doesn’t need you to make it a better place," Liles says. "You can be a freaking guidance counselor. … You’re here because you need a job. Well, this job doesn’t need you."

More push-ups and shoulder presses.

Simon and Liles double team Forni again. This time Simon grills him on his two-day stint in the Henderson police academy.

"You can’t handle the Henderson academy, and you think you can come to Metro?" demands Simon, a former Henderson cop.

Forni tries to explain. He promised he would move with his wife overseas.

Excuses, Simon says.

"You’re weak, Forni, and I’m going to break you, and I’m going to get rid of you," he grumbles. "You are not police material. Why don’t you go back to being a paper pusher?"

The round ends, and the officers march back to the building.

Five minutes later, they return to the field for the final feed.

"Claaaaass. Inspecshun!" Yanga announces.

He drops his gun’s magazine, but that’s the least of his worries.

Leslie is in his face screaming a rapid-fire stream of police codes and legal terms, and he wants answers.

"405Z"

"Attempted suicide."

"445"

"Explosive device."

"484"

"Court."

The other officers weave through the formation, spending about 10 minutes with each recruit, quizzing them on their gun’s serial and model numbers, their chain of command, how to spell Sheriff Doug Gillespie’s name (definitely not with a "J," as one hapless recruit found out), and everything else they were supposed to learn in the first week.

Any mistake earns a write-up and a homework assignment that usually requires them to write the correct answers 10 times or more.

Michelle Domanico, Zehnder says later, was so nervous that her gun rattled in her hand as he approached.

After their individual inspections, the recruits are sent to run several laps around the track and return to their positions.

Nathan Herlean says he was "sweating bullets" when Simon got in his face.

Herlean failed miserably under the pressure before being sent off to run the track.

He was supposed to return to the field after a couple of laps, but he just kept running.

"It was like they were sharks out there. Why would I go back to the feeding frenzy?" he admits months later.

Simon’s next victim is Jacob Kelecava. His hair is shaved almost to his scalp, but it’s still too long for Simon as he yanks off Kelecava’s hat.

"Who’s Elvis?"

"A singer, sir."

"No. Elvis is you."

Simon orders Kelecava to dance and sing like Elvis. The 27-year-old recruit thrusts his hips and shouts "Ow!" before droning "blue suede shoes" over and over.

Satisfied, Simon warns Kelecava to cut his hair shorter tomorrow.

"I’m turning you into a police officer, not a karaoke singer," he scowls and turns away to find his next victim.

In the middle of the feeding frenzy, Alexandria Cherry begins to faint. A couple of recruits help her to the ground. Others seem too scared to move.

"I think I locked my knees, sir," she says to reassure them.

She wobbles to her feet and is helped to a shady spot at the side of the field to wait for an ambulance.

At 9:05, two hours after it began, the frenzy is over, and the recruits run to the classroom to regroup.

After first inspection, the recruits get their first taste of being a cop.

The recruits are sent into the parking lot, one by one, for a mock complaint of loud music.

Outside, Liles and Simon, donning sparring headgear and mixed martial arts gloves, play the roles of hooligans looking for trouble.

Most recruits walk out tentatively, unsure of how to deal with the troublemakers hooting and hollering in front of them. Some freeze, hands at their sides. Four pull their guns on the unarmed men. Some walk right up to them in a brave display of stupidity. Only six make the right decision and pull out their batons or pepper spray.

The exercise, Zehnder explains, tests their reactions in a confrontational situation.

"There’s one thing we can’t teach you. That’s courage," he tells them. "If you’re scared here, you’ll be scared out there. And if you’re scared out there, you’re going to die."

Five percent of the people cops encounter on the street aren’t intimidated by the gun and badge. All they see is someone standing in the way of freedom, and they’ll kill you if they have to, he says.

This is part of the "ugly reality" in police work. It’s the side rarely shown on TV or the big screen. The side fathers, uncles and other relatives in law enforcement probably never talked about.

"This is your reality, folks, this is the world you’ve entered," Zehnder says.

A string of video clips runs on the projection screen, some aired on TV shows, some taken from dashboard cameras. All of them show the life-and-death situations facing real cops, usually without warning.

In one clip, an officer pulls a car over on a dark, isolated highway. As soon as the officer steps to the driver’s side door, he’s shot in the face.

The gunman stands over the fallen officer and pulls the trigger again. The officer is saved when the gun jams, and the driver speeds away.

In another clip, officers duck for cover outside a convenience store when an Iraq war veteran opens fire with an automatic assault rifle.

In Las Vegas, Sgt. Robert Schulz’s patrol car is peppered with bullets in an ambush by a double-murder suspect at the Boulevard Mall. Schulz returns fire and helps catch the gunman.

You will never know when it will happen, Zehnder says, and you won’t know how you will react.

"Get that word ‘routine’ out of your mind," he says.

To put a face on the life-and-death situations, Zehnder invites his best friend on the force, Sgt. Dave Valenta, to stand before the class and recount his deadly encounter with a gang member who was trying to wrestle away his partner’s gun.

Zehnder tells his own story about a nighttime encounter with gang members he had just two weeks out of field training. One gang member had his hands stuffed in his jacket and wouldn’t take them out.

The gang member walked closer. Zehnder drew his gun.

He was about to pull the trigger when another cop dived from the darkness and tackled the gangbanger.

He tells the recruits they’ll go home some nights after a near miss and know that only by the grace of God did they dodge a bullet.

"Don’t let anybody tell you these things don’t impact you, because they do," he says.

They will witness ugly things. They will see good people die in horrible ways. They will experience things they cannot speak about, not to fellow officers and certainly not to their loved ones at home.

"We wall that off," he says. "It’s a matter of emotional survival."

They will deal with a stress they’ve never known before.

They might struggle with paranoia and cynicism.

They might have suicidal thoughts.

They might go to work one day and never come home.

Those are the realities of being a cop.

Zehnder suggests ways to avoid those pitfalls, such as engaging in family and church activities, hobbies and sports.

He wraps up his presentation with all of the agency’s fallen officers, including James Manor, who died in a patrol car crash the month before.

"For the next six months, my job is to make sure your face doesn’t end up here," Zehnder says as Manor’s photo lingers on the screen.

By the time the recruits graduate in six months, three new faces will join Manor’s on the memorial wall.

Three more lessons in the reality of policing for Class 6-09.

Contact reporter Brian Haynes at bhaynes@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0281.

The Making of a CopSunday

Police academy recruits endure harsh road

Coming Tuesday

Training Days