The Vegas Strong Resiliency Center continues to be a lifeline for 1 October survivors

She had a boot print on her face.

Broken jaw.

Missing teeth.

Leg shattered in five places — now held together by plates and screws.

During the panicked rush for safety that ensued when a gunman took aim at the Route 91 Harvest country music festival on Oct. 1, 2017, Meghan Earley was trampled as thousands fled to whatever exits they could find.

Her back was stomped on, her spine damaged; she suffered severe head trauma.

It was a miserable thing to endure.

Then a resident of Laughlin, Earley lived on the third floor of her apartment building.

She could barely walk at the time.

“There was no way I was going to be able to get up and down those stairs,” recalls Earley, a retiree who now lives in Las Vegas.

While recuperating at Sunrise Hospital and Mecical Center, a social worker put her in touch with the Family Assistance Center, which soon transitioned into the Vegas Strong Resiliency Center, a provider of resources and referral services for those affected by 1 October.

They quickly sprung into action, working with Earley’s apartment manager to get her a unit on the ground floor and securing her a mover at no cost.

When Earley’s bank account was later hacked and she was short on her rent, they cut a check to her landlord.

“If it weren’t for the Resiliency Center,” Earley says. “I don’t know what I would have done.”

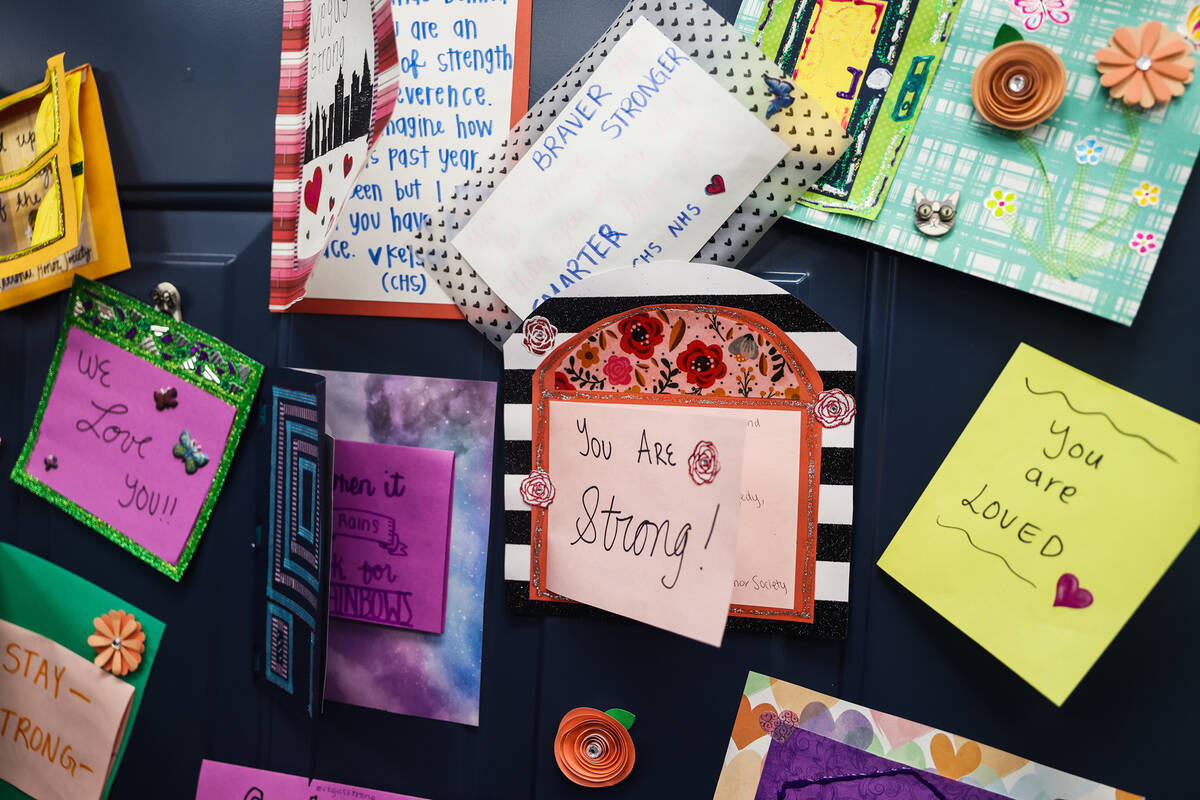

Five years after the tragedy that begat it, the Vegas Strong Resiliency Center continues to be a lifeline for many of those whose lives will never be the same in the wake of the tragedy, offering legal services, securing counseling — helping with just about anything, really.

In the past year, its mission has also expanded to include victims of violent crimes of all kinds, and not just in Las Vegas — they’ve aided those in need across the state and the country alike, as other nonprofits of its kind have come and gone.

“While centers like that were opened up all over the country after all these mass shootings, ours is the only one that’s still in existence,” Earley says. “People need to know that that center is still here.”

For survivors like her, this is no small thing, to know that as long as the center is around, someone will be there for them as they cope with a grief that probably will always be there as well.

“It doesn’t get better,” Earley explains of processing the emotional fallout of the shooting. “It just gets different.”

A Strong start

Oct. 2, 2017.

As with many Las Vegans that day, Tennille Pereira awoke to a chattering cellphone.

An attorney working for the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada, Pereira had gone to bed early the night before, only to discover the news of the worst mass shooting in American history that morning — with myriad texts from friends and family making sure she was OK.

“To think that had happened right in my backyard was terrible,” she recalls from her office at the Resiliency Center. “And then at the same time, like many people here, it was that immediate, ‘I’ve got to do something.’”

The legal aid center’s executive director, Barbara Buckley, reached out to Clark Country officials to see how her office could help.

The very next day, they were staffing the Family Assistance Center at the Las Vegas Convention Center, providing legal aid to survivors and their family members.

“Our thought was, ‘We’re attorneys,’ ” Pereria recalls. “’This is our piece of the puzzle to this community. And so that’s what we can offer.’”

When the Family Assistance Center was shuttered that Friday, the county opened the Vegas Strong Resiliency Center the following Monday.

In 2019, control of the Resiliency Center was passed to the Legal Aid Center, and Pereira was made director.

In the immediate wake of the tragedy, she dealt with several concerns, like payroll and work issues. For instance, the company that employed the bar staff at the festival initially told them that all their electronic tips were gone before Pereira and company took action — with those in the hospitality industry particularly susceptible to ongoing repercussions and in need of aid.

“A lot of them, because that’s the line of work that they were in, they don’t have the insurance, don’t have the paid time off, don’t have the benefits to really allow them to kind of go home and process what they had just been through and heal,” Pereira says. “And then on top of that, their line of work puts them back in that same atmosphere. A lot of them couldn’t go back. So they really struggled.”

The passing of time didn’t always help matters, either.

“What we’d see was employment discrimination come up a lot,” says Tyler Winkler, an attorney who works for the Vegas Strong Resiliency Center. “People went back home, and for the first year or so their employers were understanding, like, ‘OK, take your time.’

“And then after a year or two, they tell them, ‘Why aren’t you over this?” he continues. “’ It’s been a year, why aren’t you any better?’ So that does trigger a lot of federal protections.”

Another major component of the Resiliency Center’s work is helping survivors seek mental health treatment.

It hasn’t always been easy.

Prioritizing mental health

She thought she was ready to get back on the job.

It had been eight months.

Still, Shannon White knew it was going to be a challenge: The Oct. 1 survivor was employed in the facilities department for MGM Grand Resorts at the time, and one of the properties she worked at was Mandalay Bay, where the gunman was holed up.

“It was just a struggle trying to be back in a hotel environment,” she recalls, “knowing that the shooter was in the hotel at Mandalay Bay.”

And then one day everything just came to a halt.

She froze.

“I had a trigger at work with this anxiety — I just couldn’t move,” she remembers. “A couple of people I worked with saw me in distress and got me out of the area that I was at.”

White had received aid from the Resiliency Center before, and Pereira told her to reach out any time she needed help.

Now was that time.

“I called them, and they immediately got a therapist on the phone and talked me through this anxiety attack that was happening,” White says. “I never had any anxiety attacks before, but I had this trigger. They had a therapist right there, talking to me, grounding me, getting me back to where I could halfway function.”

While mental health issues are among the most widespread lingering maladies from the shooting, Pereira and Winkler were startled to discover when they started working with survivors that the Victims of Crime Program, which aids those impacted by violent acts, didn’t always cover that kind of treatment.

“The Victims of Crime program used to pay for psychological issues for some things,” Winkler says. “But there’s other categories they wouldn’t pay. The big one was lost wages.”

As an example, they cite a veteran from Washington whose PTSD was re-triggered after attending the festival.

“He was in a good place before he came to Route 91 — Route 91, set him all the way back,” Pereira says. “It brought all this stuff up.

“He came to us,” she continues, “we applied for the Victims of Crime program to get him some mental health benefits — he needed counseling, he needed to kind of go through this, again.”

His application was denied because he didn’t have a physical injury.

“He went back home, and he couldn’t work anymore,” Winkler says. “He was the primary breadwinner for the family. Normally, they’re supposed to pay you some lost wages benefits for a certain amount of time, but they wouldn’t do it, ‘we will not pay for PTSD.’”

They appealed and got him the help he needed, successfully advocating for mental health coverage.

Earley has a similar story about receiving treatment that she might not have gotten otherwise.

“I will tell you, if it weren’t for the Resiliency Center, I don’t think I would be getting any counseling,” she says. “I think I would have just said, ‘You know what? Forget it. It’s too much of a hassle. It’s too hard. I don’t have the energy.’

“If it wasn’t for the Resiliency Center helping me find a therapist,” she continues. “I would still be out there floundering.”

5 years later, fallout continues

It’s called “The Anniversary Effect.”

Tennille Pereira explains.

“The way trauma impacts the brain is that it kind of programs things, and when your senses are engaged, it can trigger those feelings and those emotions,” she begins. “And so even the time of year can bring those feelings and emotions back up, and people may not even recognize that’s why it’s happening, but it’s because of the relation to the memories and it connects it to the trauma.

“So if it’s fall,” she continues, “and there’s those smells, all of those things, can bring those feelings and emotions back up.”

And so every year around Oct. 1, the center sees an uptick in requests.

For Earley, this anniversary of the shooting resonates as a particularly anguishing one.

“It seems like it just happened yesterday — and yet I keep saying, ‘but it’s been five years,’” she says.

“Why is this one so hard? I cannot figure out why this anniversary is so hard,” she continues. “But it’s very hard. And I think, for myself and for others that I know that have survived, I know quite a few that said, ‘I don’t need counseling; I’m fine.’ And now they’re reaching out for therapy.”

As Pereira notes, even those who may feel like they have a grip on their grief, anxiety and other feelings can still find themselves unexpectedly overwhelmed.

“A lot of times, even healthy coping skills can get to a place of being unhealthy when you don’t deal with the underlying trauma, so it can come out years down the road,” she explains. “And sometimes with people that have the best coping skills and support system built in, it takes longer for that trauma to come out in their life, because they do have so much support and structure.”

To this day, the center is still getting new clients from 1 October.

“I was speaking to a first responder yesterday, and they had never reached out,” Pereira says. “A lot of times, they think they’re OK. A few years later, they’re snapping at their family. Maybe they’re drinking more or something.

“And they start to realize, ‘Maybe this is affecting me more than I thought.’ That’s very, very common,” she continues, “and a big part of why we want to make sure we’re still here.”

White has seen as much firsthand.

She went to Route 91 Harvest with 17 friends. One of them didn’t survive, but she stays in close contact with the others.

“There was one I spoke to that never reached out for any help,” White says, “never has been to any sort of therapy — and she’s losing it right now.

“She doesn’t know where to go,” she continues, “and she doesn’t know where she’s at.”

And so White gave her the Vegas Strong Resiliency Center’s number.

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram

SIDEBAR: The mission expands

She called attorney after attorney, knocked on doors, even.

"No one would take my case."

On Memorial Day weekend, 1997, Denise Batts lost her 16-year-old, Keith Batts, in a fatal DUI accident.

The woman convicted of his death was sentenced to eight years in prison and ordered to pay restitution.

Two-and-a-half decades later, the restitution still had not been paid in full and she wasn't always receiving her monthly payments on time — if at all.

When Batts tried to find a lawyer to help her file a civil suit to ensure that she received the aforementioned funds, she couldn't find any takers, especially with such an old case.

At the Southern Nevada Legal Aid Center, she had a breakthrough.

"Finally, someone at Legal Aid told me, "Well, try the Resiliency Center," Batts recalls.

There, she was put in touch with Christy Martell, a legal victim advocate, who got to work on Batts' case.

"Christy was just a light in the dark for me, because she just opened up the doors, and she just gave me the strength and the energy to go further," Batts says. "She called, she sent letters, she really did everything for me to assist that she could."

It worked: With Martell's assistance, Batts is receiving her payments once again.

Batts' story is just one example of how the Resiliency Center's mission has evolved since it was founded to help those affected by 1 October.

In June 2021, Gov. Steve Sisolak signed a bill establishing the Resiliency Center as a statewide victims center, which means its scope would expand to aiding victims of all violent crimes.

They've been helping a broad array of clients since, from Batts to a man who was shot in the head at work, suffering severe mental and physical ailments, but who didn't qualify for Medicaid and couldn't get the treatment he needed because he was an undocumented immigrant.

The center was able to get him an appointment with a neurologist who did weekly pro bono work, a pharmacy program to cover the costs of his medication and a place to live.

"He's now able to work," Pereria says. "I mean, it changed his life."

In March, the Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada received $3 million in federal funds to further broaden the services of the Resiliency Center as well as provide for the building of new facilities.

For years, the center's focus has been on helping 1 October survivors.

Now, their caseload is shifting to others.

"That balance is going the other way," Pereira observes, "which is a healthy sign. It says that there's healing going on."